During the Amarna Period, a pivotal era within Egypt’s 18th Dynasty and the broader New Kingdom, monumental changes swept through ancient Egyptian society, ushered in by Pharaoh Akhenaten. This period marked a profound shift that reverberated across religious, political, and cultural spheres, challenging established norms and traditions.

Central to Akhenaten’s transformative reign was his radical religious reform. In a civilization renowned for its polytheism, Akhenaten introduced a revolutionary monotheistic belief system centered around the worship of Aten, the sun disk deity.

This departure from traditional polytheism was met with significant resistance, as it fundamentally altered Egypt’s religious landscape and challenged centuries-old beliefs.

Akhenaten’s vision extended beyond religious doctrine. He initiated a bold relocation of the Egyptian capital from the influential city of Thebes to a new city he named Akhetaten, meaning “Horizon of Aten.” This city, strategically located between Thebes and Memphis, was envisioned as a pristine site untouched by previous religious affiliations, symbolizing a fresh start aligned with Aten’s singular worship.

Akhetaten was constructed with remarkable speed using primarily adobe, a practical choice that facilitated rapid building amidst Akhenaten’s ambitious timeline.

The city’s layout and architecture were designed to embrace Aten’s radiant presence, with open-air temples devoid of enclosed spaces, ensuring that sunlight, symbolizing Aten’s life-giving rays, illuminated every aspect of religious practice.

The city boasted 365 altars, one for each day of the year, reflecting the solar calendar and emphasizing daily devotion to Aten. Akhenaten also utilized stone and alabaster for grandiose palatial structures, showcasing his commitment to creating a capital befitting Aten’s glory.

During the Amarna Period, a remarkable innovation in monumental construction emerged with the introduction of “Talatat” — small, intricately decorated stones that revolutionized artistic expression, particularly in depicting the royal family. This new artistic approach embraced a clear, realistic style, diverging sharply from traditional norms.

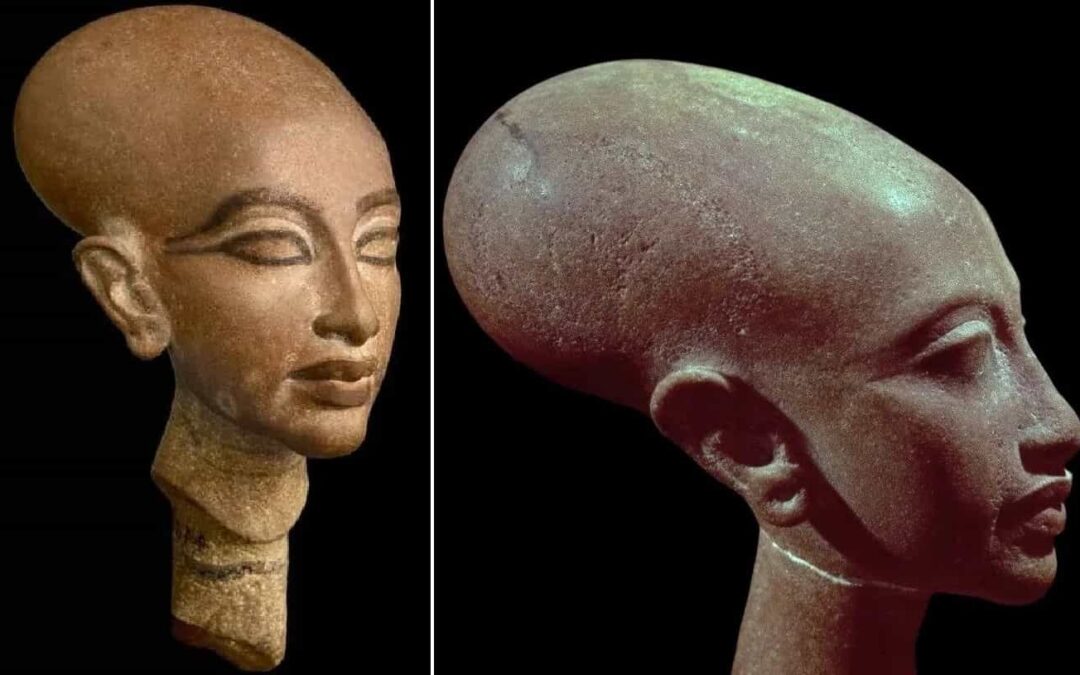

In sculpture, the Amarna Period marked a significant departure from established conventions. Statues and carved images of the pharaoh and his family abandoned traditional forms, opting instead for a more intimate and naturalistic portrayal.

Gone were the stereotypical depictions of a warrior pharaoh triumphing over enemies; instead, scenes depicted the royal family in tender, personal moments. These representations showcased unprecedented features, such as Akhenaten’s elongated limbs, almond-shaped eyes, pronounced lips, protruding belly, wide hips, and elongated skull, sparking much speculation among historians and scholars.

The rationale behind these unconventional portrayals remains debated. Some suggest Akhenaten mandated these new forms to challenge existing artistic norms and emphasize a unique royal identity. Others hypothesize that Akhenaten’s distinctive physical features may have been influenced by medical conditions, like Marfan syndrome.

The artistic revolution extended to painting as well. Naturalism dominated palatial murals during this period, depicting vibrant scenes of wildlife and flora that enveloped rooms from floor to ceiling, creating an immersive natural environment. Additionally, recurring motifs featured the royal family in reverence and adoration of Aten, underscoring the period’s religious and cultural shifts.

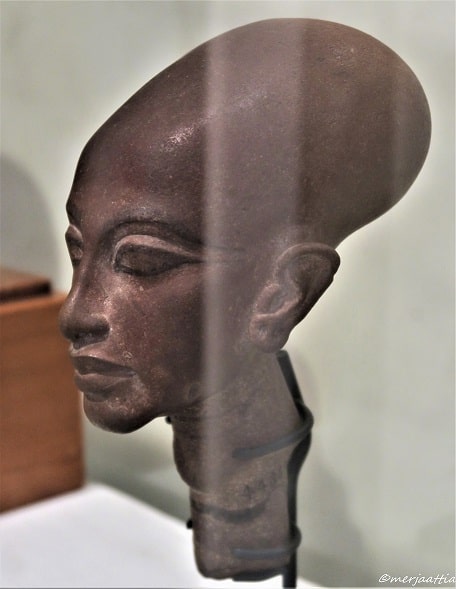

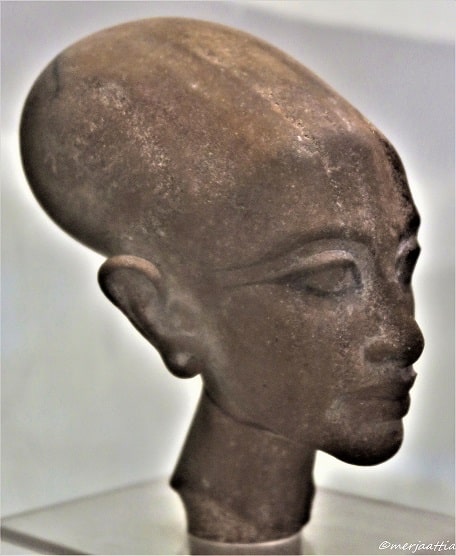

Head of an Amarna Princess

The discovery of the Head of an Amarna Princess in the workshop of Thutmose, the chief sculptor overseeing Akhenaten’s ambitious projects at Tell el-Amarna, stands as a testament to the artistic innovation of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty.

Unearthed from storage rooms among numerous other artifacts, this particular piece is believed to represent one of Akhenaten’s six royal daughters, possibly Meritaten, who held a prominent position in her father’s court. During the initial phase of the Amarna Period, princesses were depicted with elongated skulls and slender necks, a stylistic departure from traditional norms.

Early interpretations speculated on these features as either deliberate artistic choices or indicative of a medical condition, but current scholarship leans towards understanding them as deliberate mannerisms reflecting the period’s artistic style influenced by religious symbolism.

The head’s distinctive egg-shaped form symbolizes the princesses as embodiments of divine creation, echoing the depictions of Akhenaten himself. Despite being a portrait of a young woman, the sculpture emphasizes youth through soft, rounded contours, particularly beneath the chin. The eyes are large and defined with dark kohl outlines, while the ears are square and shell-like.

The protrusion above the ears signifies youthful characteristics, seamlessly blending into the elongated skull. A sensual mouth and a long chin add to the feminine portrayal, counterbalanced by a solid forehead.

Crafted from brownish-yellow quartzite, the head includes a tenon at the base of the neck, indicating it was originally part of a composite statue typical of royal representations during the reign of Akhenaten. This masterpiece is housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Location: Tell el-Amarna, Workshop of Thutmose

Period: 18th Dynasty, Reign of Akhenaten

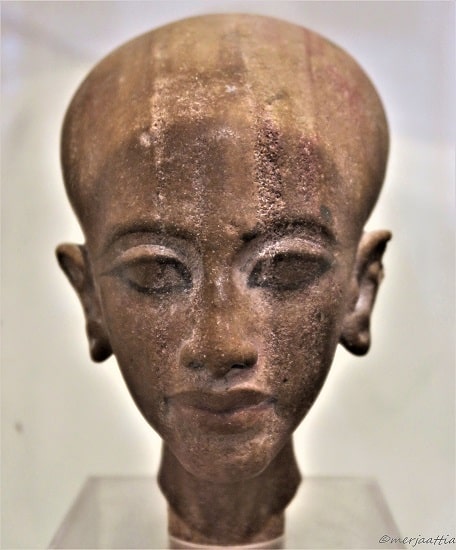

Amarna Princess

Discovered within the residence of the esteemed sculptor Thutmose at Amarna, the Head of a Princess represents a striking example of ancient Egyptian artistry. Crafted from yellow-brown quartzite and adorned with red and black pigments, this artifact exhibits meticulous craftsmanship and attention to detail.

Notably, the head features a prominent tenon beneath the neck, indicating its original attachment to a separate body, a common practice in Egyptian sculpture to create composite statues.

Evidence of ancient repairs suggests the head was broken from the neck at some point in antiquity and subsequently reattached, highlighting both its historical significance and the care taken to preserve such esteemed artworks.

Location: Tell el-Amarna

Material: Yellow-brown quartzite with red and black pigment

Current Repository: Egyptian Museum, Cairo