The Egyptian pharaoh, ruler of Upper and Lower Egypt, owned all of the land, made offerings to the gods and maintained ma’at. But surrounding the king were his officials – and it is these powerful men who ran the palace and the country.

These officials are regularly attested on amazing monuments, but often very little is known about them. However, drawing parallels with other, better-known cultures, we can assume that these men made important decisions that affect the history of the country.

Many Egyptian wars were most likely fought by generals, not by kings. Building projects were commissioned by kings, but all the actual work of planning and organisation was carried out by the officials in charge.

In times where there was a weak or simply a lazy king, it is most likely that one or more officials were the people who were really in charge of the country.

However, this is often not visible in the sources and we can only guess by the size of their monuments that a certain courtier was indeed powerful.

The Rise of the Chancellor

One important office in the Middle and early New Kingdoms was that of the ‘chancellor’ often translated as ‘treasurer’, ‘overseer of the seal’ or ‘overseer of sealed things’.

The officials holding this position at the royal court were often as influential as the vizier, and in the Thirteenth Dynasty, some of them are better attested than many of the short-reigning kings.

Chancellors are not attested at the royal court of the Old Kingdom, when the ‘vizier’, ‘overseer of the treasuries’ or ‘overseer of the granaries’ were the main men around the king.

However, ‘chancellors’ appear in private estates. Most officials and local governors employed a staff of people, which included a ‘steward’ who looked after the house and the fields. But there was also a ‘chancellor’ who was responsible for the belongings of the officials and governors.

The royal court of the Middle Kingdom was different from that of the Old Kingdom. In the First Intermediate Period, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms. Around 2100 BC, one local governor at Thebes took on royal titles and founded the Eleventh Dynasty.

A Theban ruler of his line, Mentuhotep II, finally managed to reunite Egypt around 2000 BC, ending the First Intermediate Period. The rulers of this dynasty were at the beginning local governors.

Their court was organised like a governor’s court and not like a king’s court. The two most important people at this local court were the ‘steward’ and the ‘chancellor’. When these local governors became kings, their local officials suddenly became state officials.

The chancellor was in charge of the palace as an economical unit, controlling the incoming goods. These included food, but also measures such as jewellery, linen and other commodities needed at the royal court.

The chancellor sent out expeditions to gain materials for the palace, but he also directed important building projects. The early Eleventh Dynasty chancellor Tjetji describes some of his tasks:

“The treasure was in my hand under my seal, being the best of every good thing brought to the majesty … as tribute from this entire land”

(translation after M. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol. I, 1975, p.91).

The office of chancellor had its heyday in the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period. The list of Middle Kingdom chancellors reads almost like a roll call of famous Middle Kingdom officials.

Khety

Khety held office under king Mentuhotep II. He had a huge tomb at Deir el-Bahri (TT 311), next to the funerary temple of his king.

The tomb was found in a heavily destroyed state, its fine limestone reliefs used in the Ramesside Period for making stone vessels.

Nevertheless, the remains show that they were of highest quality, most likely the work of a royal workshop. It is possible to reconstruct some scenes and remarkably there is a depiction of Mentuhotep II in the tomb chapel.

This is the oldest Egyptian tomb chapel so far to have a depiction of the king — images of kings never appear in Old Kingdom mastabas or rock-cut tomb chapels. Evidently, Khety received special favour.

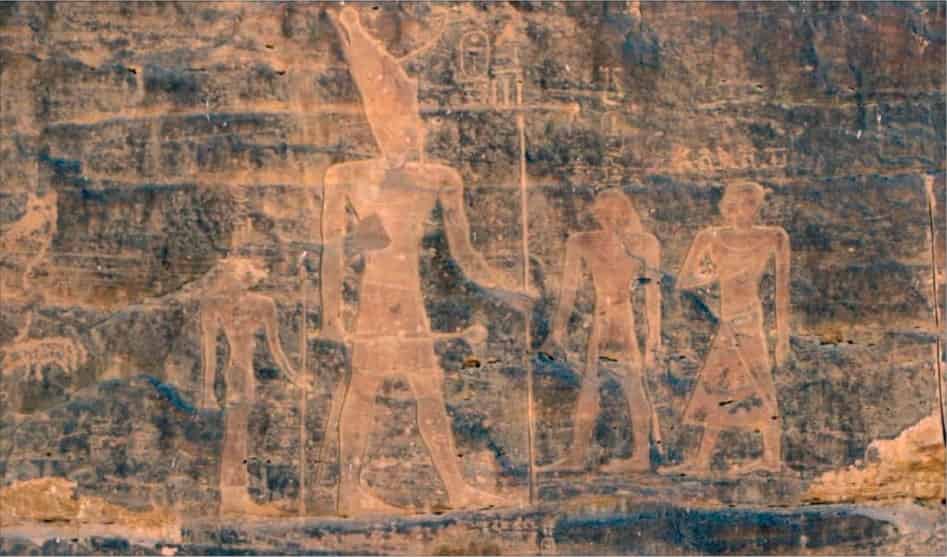

Another sign of his exceptional status is a depiction in rock carvings at Shatt er-Regal, in the most southern part of Egypt, just north of Aswan.

Here is preserved a relief showing king Mentuhotep II, his mother Iah, an enigmatic person called Intef and Khety. Khety was evidently so important that he was represented together with the king and the king’s mother.

This is rarely attested for other officials. However, the texts and titles around Khety and the king are silent about his position. We can only guess at why he was honored in this way, and one wonders whether he was related to the king’s family.

He bears the title ‘father of the god’, which might indicate a very special relationship, but the exact meaning of the title is enigmatic.

Later the title is some times used for a non-royal father of a king, but as Mentuhotep II was the son of Intef III, this could not be the case here.

That leaves the possibility that Khety was the father of a queen, or perhaps the educator of the king’s children, a function attested for the title ‘father of the god’ in the New Kingdom.

Mentuhotep

Another very important chancellor was Mentuhotep who served under Senusret I (Twelfth Dynasty, c. 1950 BC). Mentuhotep is again known from a huge tomb that was located close to the pyramid of his king at Lisht.

The tomb chapel was found heavily destroyed and only small fragments of the relief decoration survive. In the underground burial chambers, two stone sarcophagi were found; one was well preserved and decorated on the inside with friezes of objects and coffin texts; the second sarcophagus was found smashed into pieces.

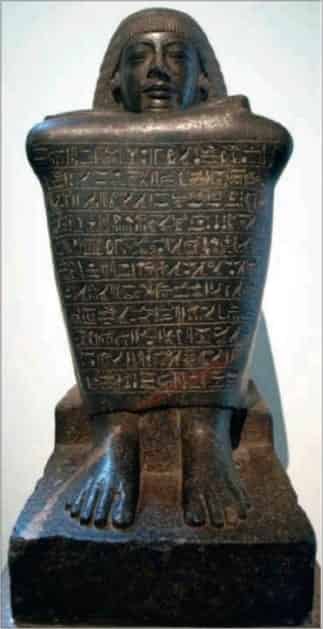

Mentuhotep is also known from a series of statues, most of which were found at Karnak, which show him sitting on the ground with a papyrus roll on his legs.

Indeed, Mentuhotep is the Middle Kingdom official with the highest number of statues preserved. On many of them he bears the title ‘overseer of all royal works’. Under Senusret I, the Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak was greatly enlarged and rebuilt.

It seems that Mentuhotep was the mastermind behind this expansion and the leading builder of the new temple complex that formed the foundation for the later huge New Kingdom temple.

Mentuhotep most likely also constructed the Osiris temple at Abydos, which was rebuilt under Senusret I. It seems to have been an important and impressive complex.

Not much of it has survived, but it is mentioned in later texts specifically as a building of Senusret I. In the Middle Kingdom many officials had a chapel at Abydos, so that they could be close – at least symbolically – to Osiris, Lord of the Underworld, who was thought to be buried there.

From Mentuhotep’s chapel, only one stela and the fragment of a false door have survived. The stela is inscribed with long lists of titles but also mentions his building work at the temple at Abydos. However as with Khety, not much more is known about Mentuhotep’s life.

We do not know who his father was, and we do not know his exact relationship to Senusret I. It is clear, however, that he was a powerful man, who carried out many important tasks and who was given many privileges – including a huge tomb next to the king’s pyramid.

The Hyksos Period

Very little is known about the administration under the Hyksos in the following Second Intermediate Period, c.1650- 1550 BC. The Hyksos were most likely from the Levant, and ruled mainly in Egypt’s eastern Delta.

There is a group of kings from the period (albeit not Hyksos for certain), who bear an Egyptian names and are only known from a high number of scarab seals.

The best attested is a certain king Sheshi. Similar in style and production to these kings’ scarabs are scarabs naming chancellors.

The best attested is Har (perhaps to be read as Hur, the same name as the famous Ben Hur) who is known from more than a hundred such seals. Only three titles are attested for him: ‘royal sealer’, ‘sole friend’ and ‘chancellor’. Despite this, he must have been a very powerful man.

It is often assumed that he was in office under king Sheshi, as this king is the best attested king of the period on scarab seals, and Har the best attested official on scarab seals. But this remains speculation.

The high importance of the chancellor under the Hyksos is surprising as there are almost no other offices attested under the Hyksos and related kings.

There are no viziers during this period. This may be because the role of the Egyptian vizier had much to do with writing and scribal offices at the palace.

In the Levant, writing was not common at this time, so when the Hyksos arrived in Egypt, they most likely chose an office that was also known from their own world. This was the chancellor who managed the commodities of the palace.

A similar picture emerges when looking at the contemporary Theban Seventeenth Dynasty – the Egyptian kings who fought against the Hyksos.

Only one king’s burial from this dynasty has so far been found, belonging to king Nubkheperra Intef Next to the king’s pyramid was discovered a small, but decorated tomb chapel, belonging to an official named Teti.

It was the only well-preserved chapel found there and again belonged to a chancellor. The importance of these officials is also visible at the end of the dynasty under king Kamose.

Several stelae reporting on the king’s wars against the Northern enemy were set up at Thebes. The best preserved stela does not show a depiction of the king, but instead the chancellor.

Neshi is shown on the stela, standing in the lower half on the left side. He bears an impressive list of titles such as ‘overlord of the entire’ and ‘overseer of the (king’s) friend’, but again, besides these titles, nothing is known about him.

However his image on this important royal monument demonstrates the outstanding position of the office of chancellor during this period.

New Kingdom

The chancellors of the New Kingdom are still key officials but is seems the office lost importance. Viziers are not well attested in the Second Intermediate Period but became the highest civil office once again during the New Kingdom.

Next to the chancellor, the ‘high steward’ became another important office. The Theban tombs of the high stewards are impressive monuments.

Ironically, due to the higher number of preserved sources from the New Kingdom in general, we know much more about the activities of the New Kingdom chancellors.

Ahmose, in office under Amenhotep I (c. 1500 BC) came from a powerful local family at Elkab. Nehsy was in office under Hatshepsut, had a tomb at Saqqara and is mentioned in connection with the famous Punt expedition.

Meryra was in office under Amenhotep III and had a rock cut tomb at Saqqara not far from that of Nehsy. He was in charge of educating the prince Zaatum. This was certainly a prestigious task, but his tomb is rather modest and he is not known from monuments outside of his tomb.

This is in stark contrast to the high steward Amenhotep, who is known from his tomb at Saqqara but also from several dozen other objects, such as stelae and statues. Amenhotep was one of, or even the most important figure at the royal court at Memphis; Meryra appears minor in comparison.

It is also revealing that there is no chancellor known for sure dating to the reign of Akhenaten. However, another official appeared in the early Eighteenth Dynasty: the ‘overseer of the treasury’.

The title was important in the Old Kingdom, but did not exist as an office in the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period. It appears again in New Kingdom and it seems that these officials took over the functions of the chancellor.

Now it was the ‘overseer of the treasury’ who was in charge of the commodities at the palace, not the chancellor. The importance of these officials is clearly seen in Tutankhamun’s regin.

At Saqqara, in the cemetery where many officials of the king where buried, there is the huge tomb of the general and high steward Horemheb, who later became king, the smaller tomb of the high steward Iniuia, and the large tomb of the overseer of the treasury Maya, providing evidece for the outstanding influence and resources of that man.

Source:

Wolfram Grajetzki, Ancient Egypt.

Grajetzki, W. (2009) Court Officials of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. London: Duckworth.