Fayum Portraits

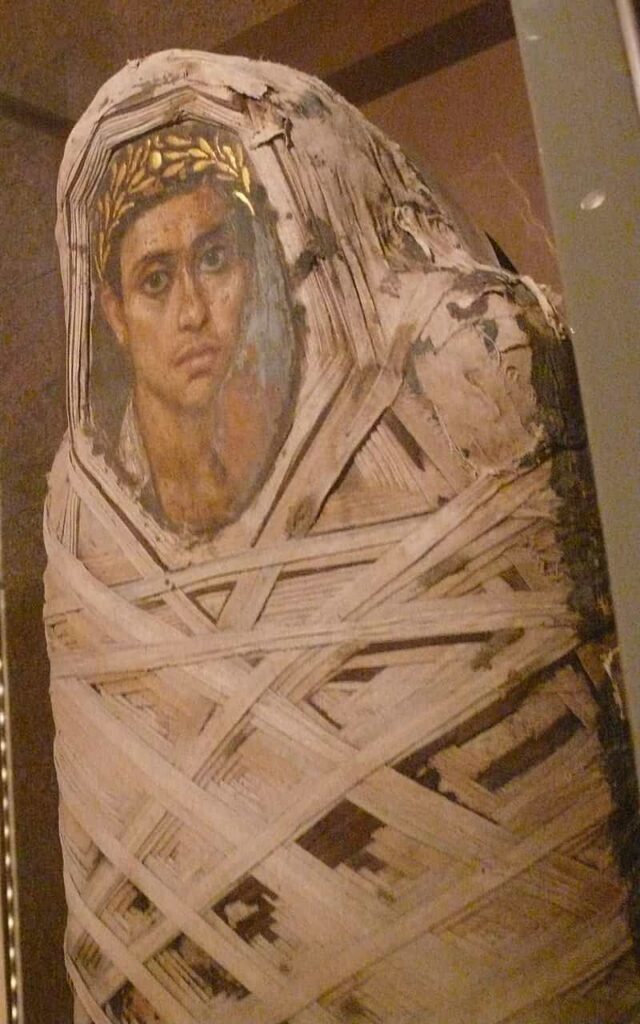

These paintings of Roman tradition, placed between the bandages and the face of the mummy to replace, in some cases, the traditional ancient Egyptian masks that protected and identified the deceased, are known as “Fayum portraits” due to their origin.

Although similar portraits have been found in various locations in Egypt, such as Saqqara, Antinopolis, and Thebes, the greatest number of these portraits have been discovered in the Fayum region. Therefore, today we have a gallery of characters that allows us to accurately know the faces of men, women, and children who lived in Egypt between the 1st and 4th centuries BC.

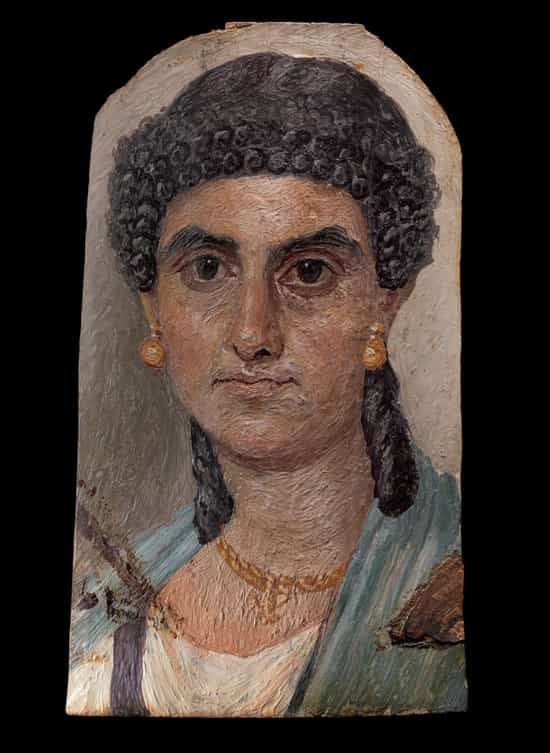

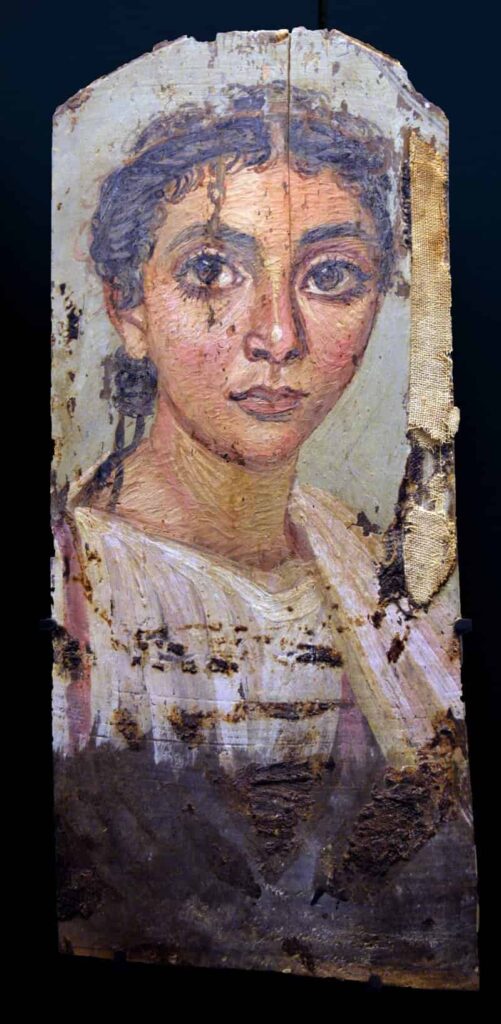

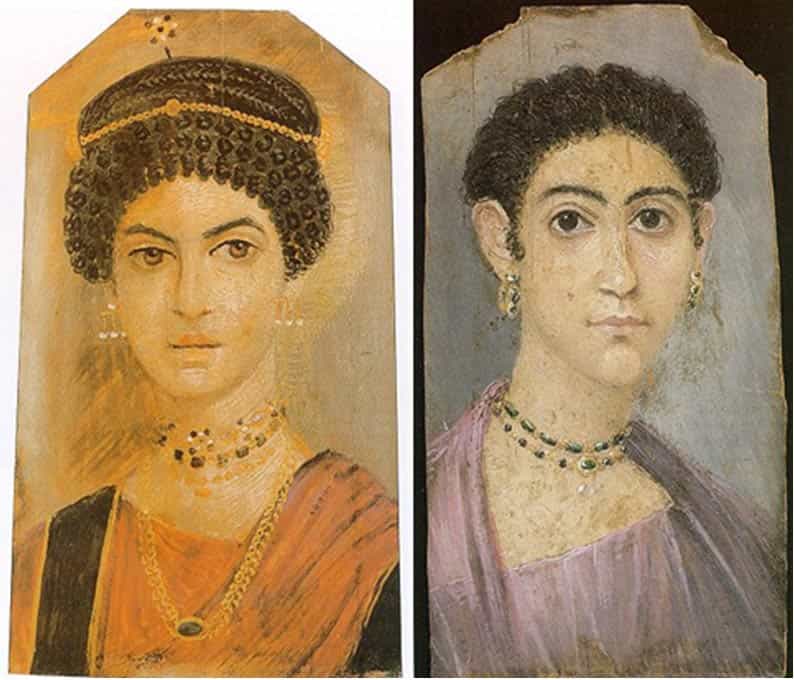

Dating most of these portraits accurately is not easy, as they were excavated from their tombs at the end of the 19th century or the beginning of the 20th century without much scientific rigor. However, stylistic analysis and the evolution of fashion, clothing, jewelry, and particularly hairstyles, enable us to specify the period of their creation in more detail.

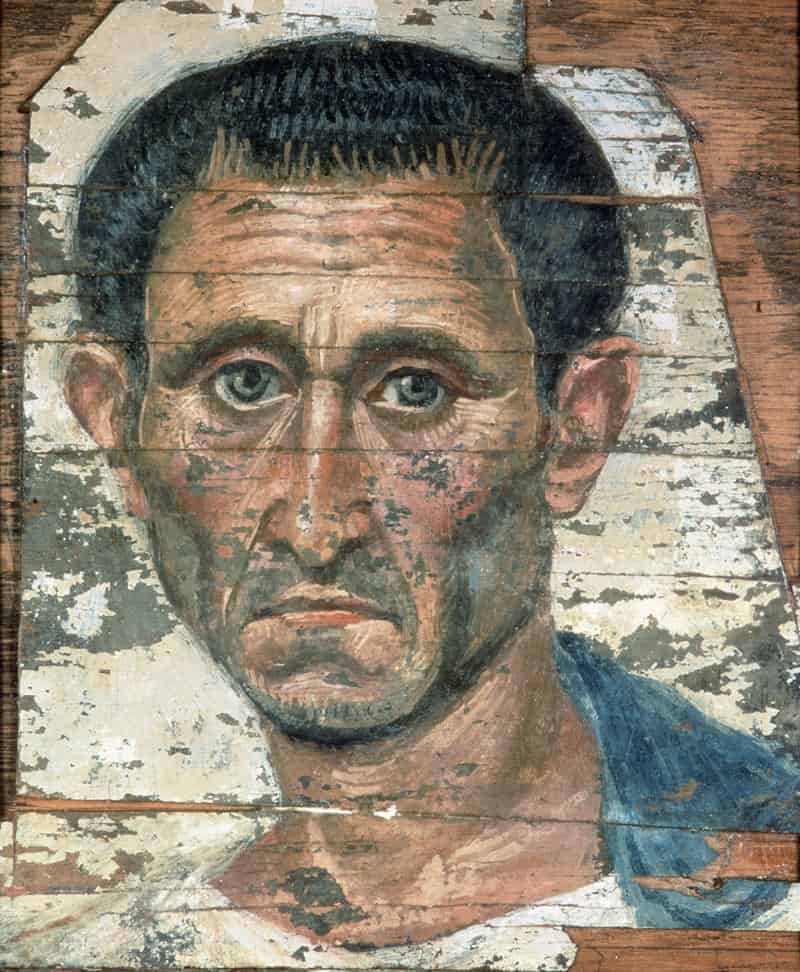

Some of these portraits can be considered true works of art due to their execution and personality, as well as the strength and vitality exuded by the individuals depicted in them.

Others, however, are conventional and stereotypical representations, particularly in the case of depictions of children. The simplified eyes, mouth, and facial features are clear indications of mass production.

At first glance, one can observe an evolution of styles. Portraits from the 1st and 2nd centuries, which are almost realistic, bear the influence of Hellenistic idealization, characterized by soft and gentle features.

During the 2nd and, especially, the 3rd centuries, this idealization led to an exaggerated, almost caricatural realism, resulting in a hieratic and impersonal representation in the 4th century. These portraits are characterized by large eyes and a fixed gaze, indicating a strong Eastern influence.

Mysterious Faces

Examining these paintings raises a series of questions that are not always easy to answer. Who were the artists? Did they work in specialized workshops or, conversely, did they carry out their work in a nomadic manner, traveling across Egypt with their materials and stopping wherever they were needed? Based on their works, we know that there were both highly skilled artists and mere copyists who produced paintings in series and on commission.

Upon close examination of the depicted faces, it becomes evident that these portraits were painted during the subjects’ lifetime, not after their death.

The sparkle in their eyes or the gentle color of their cheeks conveys a sense of vitality that is not devoid of a restrained acceptance of the inevitable end that awaits them.

Some experts believe that these portraits were displayed in homes and then handed over to embalmers after the individuals’ death, to be placed between the mummy’s bandages.

Another point of controversy is the age of the depicted individuals. Does the age shown correspond to their age at the time of death? Most of the portraits faithfully reflect young individuals, not older than thirty years old; examples of middle-aged men and women are rare, and children constitute a significant portion.

Despite the understandable idealization of the subjects, these images can provide crucial insights into determining the prevailing life expectancy during a time marked by a high infant mortality rate.

Status and Miscegenation

It is worth considering whether the expensive jewels adorning the female figures reflect the social status of the deceased and signify their actual purchasing power.

Regardless of the value of the jewels, it is evident that their style, along with the hairstyles, dresses, and other accessories, aimed to imitate the fashion worn during that time by the elite ladies of the Empire’s capital.

Another striking aspect of these portraits is the noticeable presence of miscegenation in the physiognomy of the subjects. The coexistence of Egyptian farmers, Greek-origin soldiers displaced to the area, and settlers during Roman rule seems to have contributed to this diversity.

We have knowledge of the identity and occupation of some of the individuals depicted. For instance, we can refer to Hermione, the Greek grammar teacher; Isadora, the elegantly dressed matron in a tunic, veil, and adorned with jewels and a crown; or Artemidoro, who bids farewell with a succinct “goodbye” while wearing a golden laurel wreath in his portrait.

This fact is not at all surprising when considering that retaining one’s name was essential for being remembered and achieving eternal life, as it constituted a vital part of one’s identity. This idea is not new, as evidenced by the practices in Egypt and Rome of damnatio memoriae, a judicial punishment where any trace of an individual’s identity, including their name, was eradicated.

Thus, extending beyond impersonal art, the polychrome panels of El Fayum encapsulate not only physiognomies but also the essence of characters, emotions, and a longing for endurance, perhaps as unattainable today as it was in the past.

Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic