In ancient Mediterranean cultures, including Egypt, hair symbolized vitality and the essence of life. It was not something a person could control; it grew naturally, even for a while after death. For this reason, hair carried deep symbolism.

People often felt that their hair represented their individual power and energy. The loss of hair or the appearance of grey strands could evoke feelings of vulnerability, as if their youth, strength, or health were slipping away.

In many societies, to be seized by the hair was a clear sign of defeat and submission. This idea was present in Egypt as well, where pharaohs would often depict themselves grasping their enemies by the hair, a symbol of their dominance.

This concept wasn’t unique to Egypt—across various ancient cultures, allowing someone to touch or control one’s hair indicated surrender or deference. Among the ancient Greeks, for instance, a simple gesture involving the beard could signal submission or even a plea for mercy. Similarly, in Germanic traditions, touching another person’s hair or beard symbolized trust or adoption into a group.

Hair rituals were deeply significant throughout various stages of life in ancient societies. Key life events such as entering adulthood, becoming a mother, or participating in priestly roles were often marked by ceremonial practices involving hair. These rituals reinforced the connection between hair and major life transitions, including funerary rites.

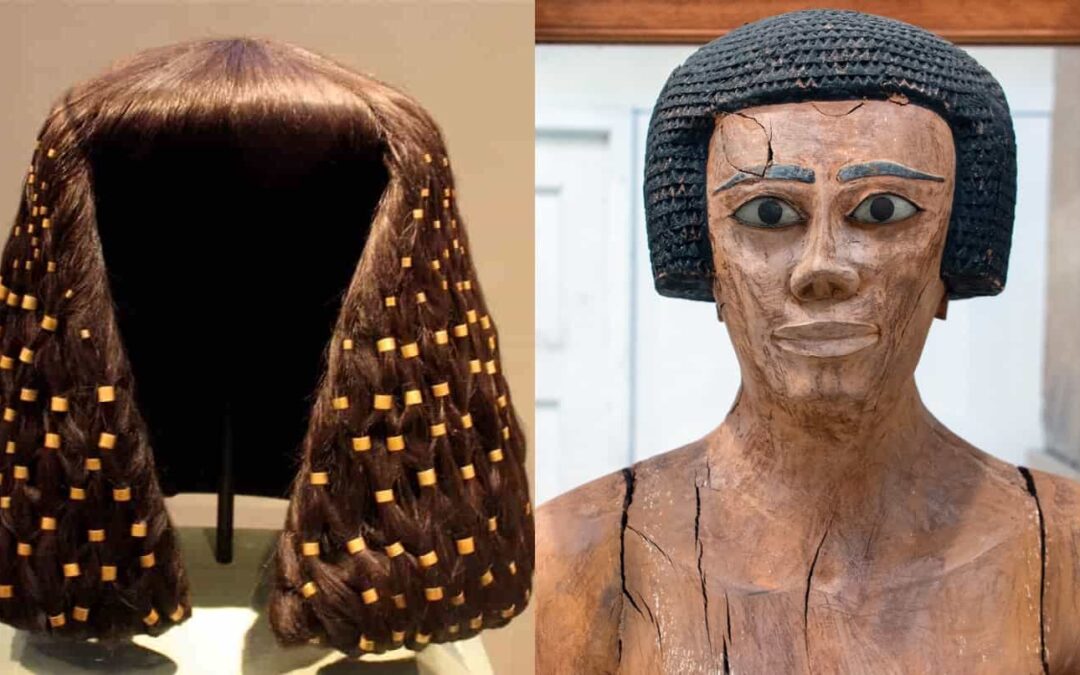

In ancient Egypt, the importance of hair extended far beyond simple grooming. Hairstyles and wigs played a crucial role in expressing status, power, and identity. Let’s explore how these elements of personal appearance were vital in ancient Egyptian culture.

Hair in Ancient Egyptian Life: Style, Health, and Myth

It is likely that most Egyptians had dark or black hair, typical of Mediterranean populations, whose hair is generally thick and robust. Yet, as with many other aspects of Egyptian life, the climate—particularly the intense heat—shaped their approach to hairstyles.

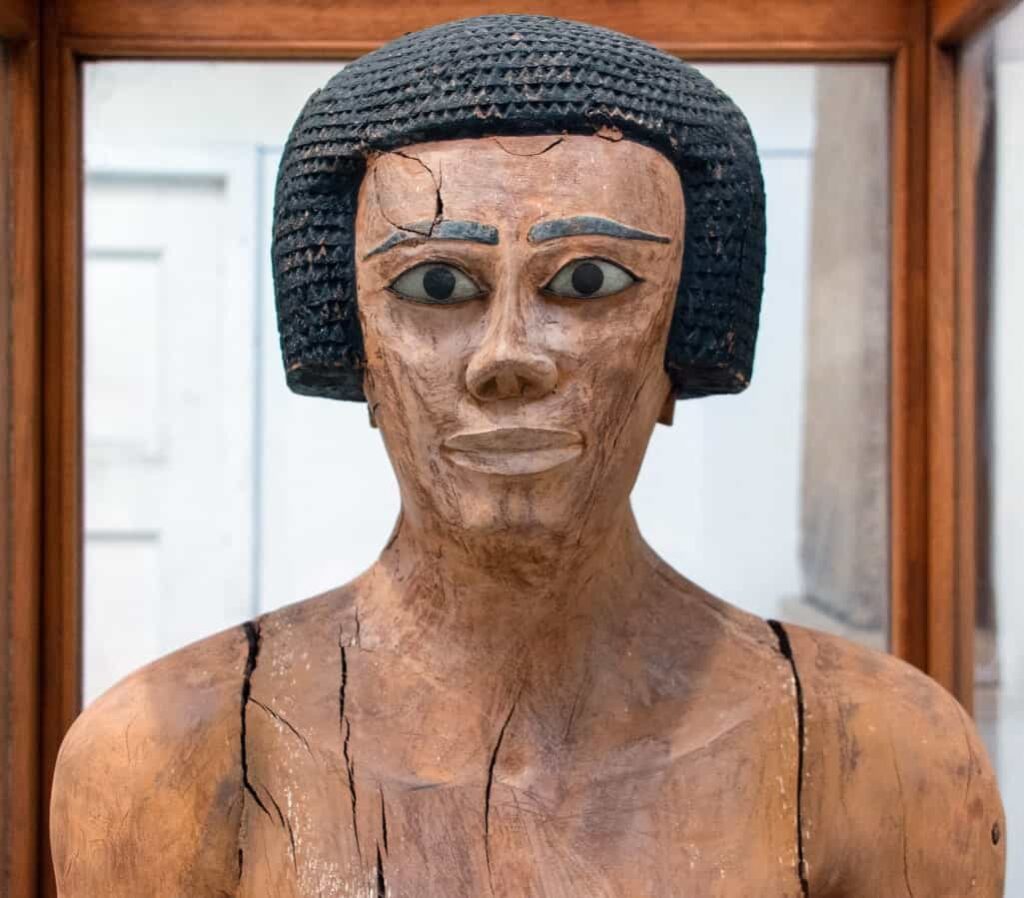

Both practicality and environment led Egyptians to keep their hair short or even shaved, especially among men. Women often sported a short, square-cut style, while men preferred very short hair, similar to some contemporary styles.

For the working classes, short or shaved hair was a logical choice, helping them cope with the heat and avoid issues such as lice. In fact, removing all body hair was a common practice for similar reasons.

Hair and scalp care were priorities for Egyptians, driven by concerns about aging, baldness, and even grey eyebrows. The Ebers Papyrus includes remedies for these issues, such as dyes designed to restore youthful appearances and potions that could allegedly cause hair loss in rivals.

One notable concoction meant for hair loss prevention mixed fats from various animals, including lions, hippopotami, and crocodiles. Whether these methods were effective is unknown, though the ongoing battle against baldness suggests otherwise.

Hair also carried symbolic meaning in Egyptian mythology. For instance, the goddess Isis, upon discovering the death of her husband Osiris, cut off a lock of her hair before setting out on her journey to recover his body. This act of mourning highlights how hair was intertwined not only with daily life but also with spiritual and emotional expression in ancient Egypt.

The Role of Hair in Egyptian Funeral Rites and Society

Hair played a significant role in ancient Egyptian funeral customs. Mourners, both men and women, were often depicted with disheveled hair, and it was common for grieving women to tear at their hair and sprinkle ashes on it as part of their expressions of sorrow.

Additionally, small braids or curls of human hair have been found carefully preserved in many burial sites, stored in boxes. Whether these were extensions, hairpieces, or tokens of affection for the deceased remains unclear. They may have been part of the burial goods, similar to full wigs, or simply a sentimental offering left by loved ones.

In royal circles, the care of hair and wigs was entrusted to professional hairdressers and barbers. Both men and women in the upper class would regularly tend to their appearance with the help of these experts, who also maintained their nails and other grooming needs. Official depictions often show this level of personal care as a daily routine, though it’s unclear how accurate these portrayals are.

The Amarna royal family, however, is the exception to many of these practices. Numerous depictions of Pharaoh Akhenaten, Queen Nefertiti, and their daughters show them with shaved, elongated heads, a distinctive look associated with their unique artistic style and perhaps religious beliefs.

For the average Egyptian, visiting the barber or hairdresser was a more occasional affair. Workers in the lower classes would sometimes line up outside the barber’s shop, taking naps in the shade while waiting their turn to have their heads shaved. Scenes from the tomb of Userhat (Tomb 56 in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna) illustrate this practice.

In ancient Egyptian society, hair length often served as a marker of social status. The wealthier a person was, the longer they could afford to grow their hair. Maintaining long hair under the intense Egyptian sun was impractical for laborers, as it would become dirty and unkempt. Only those who had servants to care for and braid their hair could keep it long, signaling their higher status and wealth.

Determining whether hairstyles in Egyptian art were natural or wigs can be challenging. Elaborate styles, like those worn at banquets or depicted in tomb decorations, were undoubtedly wigs. However, more modest hairstyles sometimes raise questions, as they could feasibly be created with natural hair. The distinction between natural hair and wigs often remains ambiguous in historical representations.