An interesting experimental archeology project recreates the way in which the ancient Egyptians baked bread and has even recovered the possible recipe they used to make the dough.

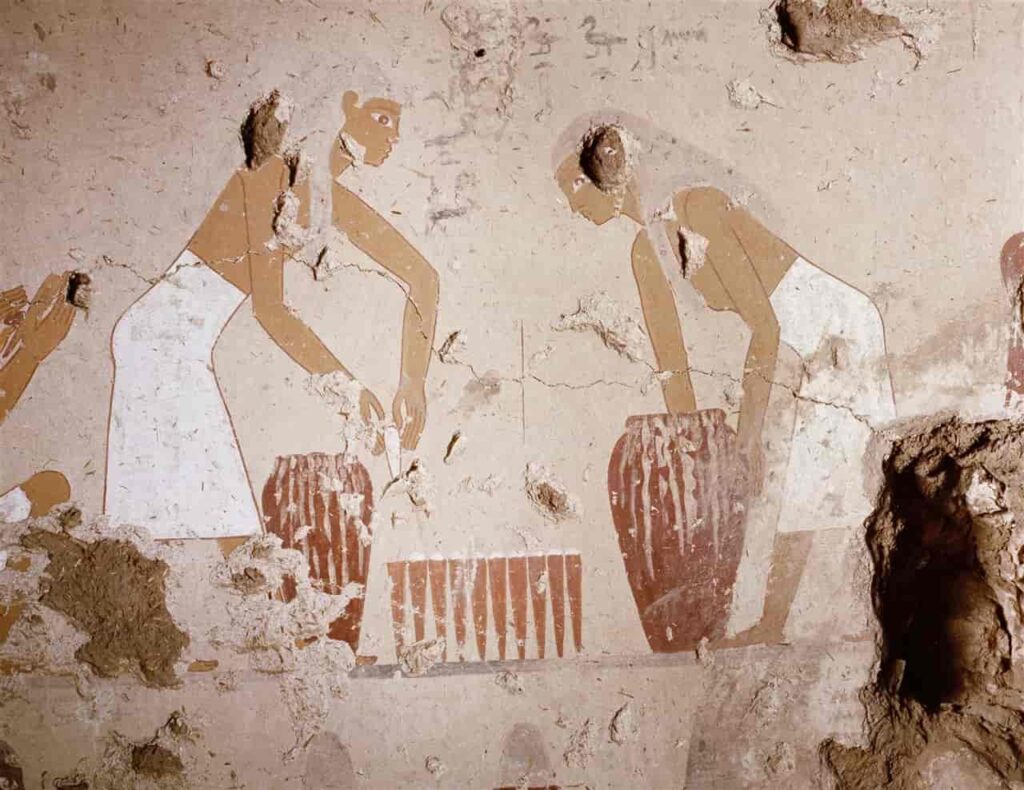

Do we know how the ancient Egyptians baked bread? The subject has long drawn the attention of archaeologists, especially due to the large number of remains of culinary vessels that have been preserved, and even the numerous iconographic evidence that shows the baking of the dough in conical molds.

Now, Adeline Bats, a researcher at the Sorbonne University, has decided to take up this matter again and undertake an interesting experimental archeology project: Baking bread with the aim of discovering the ancient technique used to make it, including the recipe.

“The production of bread is well documented in pharaonic Egypt, particularly through images of food processing that form part of the decoration of the tombs of the elite of the Old and Middle Kingdoms, as well as the so-called ‘bread molds’, ceramic cookware found in large quantities at archaeological sites.

Yet despite this abundant documentation, the chaine operatoire is not well known or understood,” explains Bats in an article that has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The project has received funding from Mondes Pharaoniques (CNRS, UMR 8167, Orient & Méditerranée), directed by Pierre Tallet, and the participation of the Franco-Egyptian archaeological mission in Ain Sukhna (Egypt), directed by Claire Somaglino from the University of the Sorbonne and by Mahmoud Abd el-Raziq of the Suez Canal University.

These experiments have been carried out in collaboration with Georges Verly, from the Sorbonne University, and Roland Feuillas, a baker from Cucugnan (Les Maîtres de Mon Moulin).

Recreate an ancient culinary technique

Adeline Bats started this project, which is part of her doctoral thesis, by analyzing the iconography that has come down to us about baking bread.

Most of the images that show this process dating from the Old Kingdom (2750-2250 BC) are usually represented in burial places and can be grouped into three phases: Heating the mold in the fire, removing it and pouring the mass inside.

During the Middle Kingdom, the molds seemed to be heated in a hearth and then filled with semi-solid dough.

To carry out her experiments, the archaeologist decided to heat and bake the bread in open hearths in shallow pits. “For all experiments several bread molds were produced in Aubechies (Belgium) and Ain Sukhna (Egypt), all from local clay. Fresh donkey dung and gravel were used as tempera. The pots were fired in open hearths at temperatures of between 850 °C and 950 °C,” says the researcher.

While bread has been a staple of the human diet for millennia, made by kneading a mixture of flour and water, the specific recipe used by the Egyptians was unknown until now.

The findings of organic matter in different archaeological sites indicate that two types of grains were cultivated in ancient Egypt: Common barley and a variety of wheat called Emmer, which apparently was the first cereal cultivated by humans.

It was essential to work with at least one of these ancient plants, which are rarely cultivated in the world today. Roland Feuillas, farmer-baker and specialist in ‘old wheat’ varieties, was invited to participate in this research project and provided an organic ‘Black Emmer’ flour.

This cereal was the one used during all the experiments. The Emmer produces a tasty, low-gluten and highly digestible flour.

In the absence of reliable data on the use of yeasts and sourdoughs in association with the conical bread pans used during the Middle Kingdom, I opted to carry out various tests with the spelled (Triticum monococcum) sourdough at our disposal, or with long spontaneous fermentations Bats recounts.

A perfectly baked loaf

The researcher carried out several experiments, with different mixtures, temperatures and humidity levels, with the aim of obtaining “a perfectly baked bread (without traces of charring or with a soft semi-baked appearance) that detaches perfectly from the ceramic without breaking”.

During the study, 54 different breads were made. After several attempts, the most successful dough was made up of the following recipe: One kilo of 100% bran black Emmer wheat flour, 15 grams of salt, 170 grams of einkorn sourdough starter and 750 grams of water.

The technique also involves coating the inside of conical loaf pans with a layer of fine sandy clay, heating the pans horizontally, and shaping the dough into elongated pieces beforehand.

“After 60 minutes of firing at between 100°C and 120°C, the dough inside the molds was already fully baked. During the firing process, it loosened slightly from the ceramic and a crust formed on the inside, thanks to the presence of the sourdough, a dense ‘honeycomb’ was formed that allowed the good distribution of hot air during cooking”, explains Bats.

In this way, the molds did not break when extracting the loaves, and only a small amount of charcoal was used to bake several loaves at the same time.

The experiment carried out by Adeline Bats and her collaborators can shed new light on an ancient cooking technique and contribute to highlighting the importance that such a basic food in the human diet, such as bread, has had since ancient times.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic