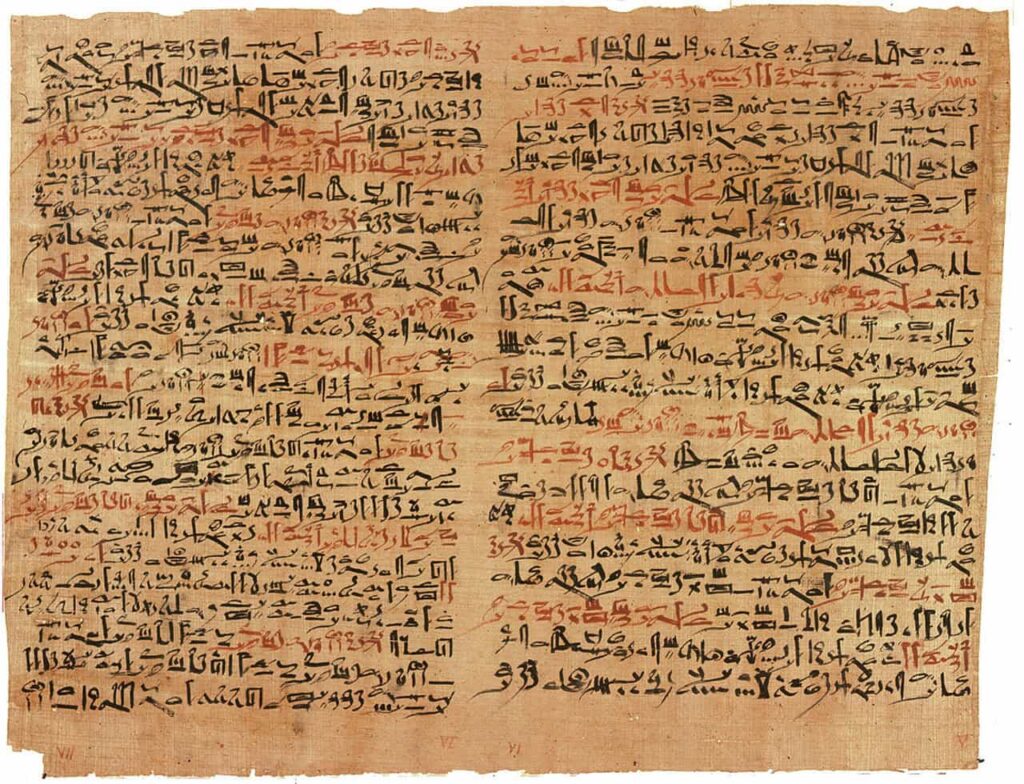

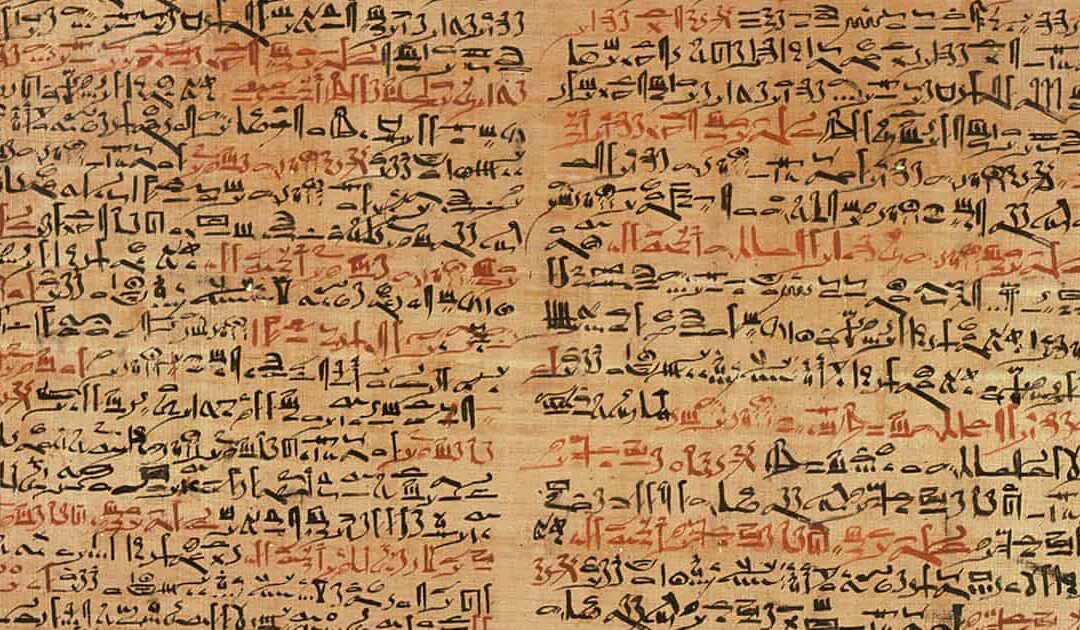

The “Edwin Smith Papyrus” is an ancient Egyptian medical treatise, written in hieratic language, possibly one of the oldest medical treatises in history. This document is one of the fragments that were part of an ancient Egyptian surgery book and, according to some researchers, could have been composed as early as the Old Kingdom, around 4,500 years ago.

The ancient Egyptians believed that health problems were due to human anatomy, which they considered very simple, and are reflected in the so-called “Heart Treatise”, one of the parts into which one of these medical texts is divided, the Medical Papyrus Ebers, compiled around 1500 BC during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep I.

It describes a number of diseases and their corresponding treatments. But among all these ancient medical treatises, there is one that stands out for its importance and antiquity: the Edwin Smith Papyrus.

A unique treatise

The Edwin Smith Papyrus owes its name to an American adventurer and antiquities collector who bought some fragments in 1862 from the Egyptian antiquities dealer Mustafa Aga in Luxor.

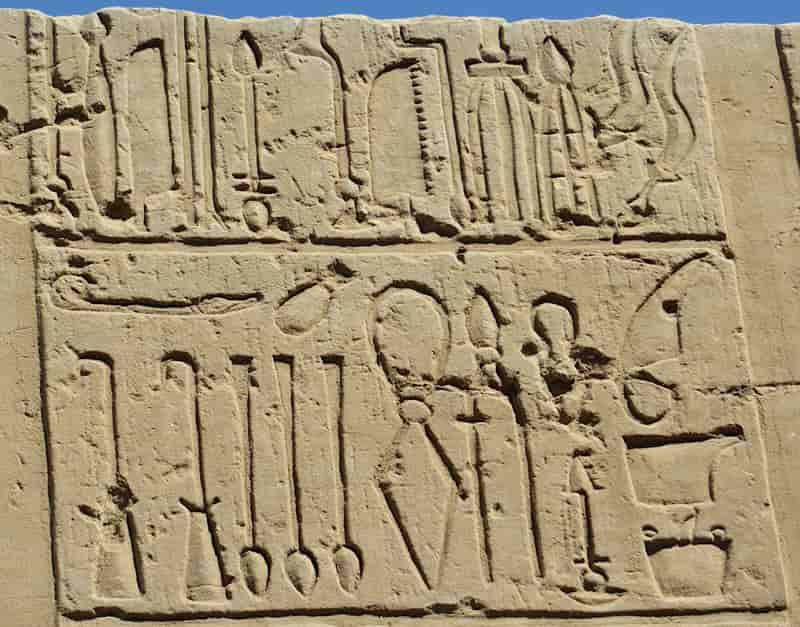

The papyrus, 468 centimeters long by 36 centimeters wide, is written in hieratic script (a simplified version of the hieroglyph, used in religious, medical, and administrative documents) and apparently not the work of a single scribe, but of several.

It was composed at the beginning of the 17th Dynasty (around 1540), although apparently it is a copy of much older texts, possibly dating to the Old Kingdom (2543-2436 BC). Some even say that its author was the wise Imhotep, architect of the stepped pyramid of Saqqara, who was deified as the patron saint of medicine in the Late Period.

This document describes a series of treatments to cure 48 cases of war wounds, as well as traumatic surgery. It also includes anatomical observations and medical examinations, finishing with the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous injuries.

All the treatments are described rationally, and only one of them resorts to magical arts. The papyrus also contains the first descriptions of cranial sutures, meninges, as well as cerebrospinal fluid. The text shows that Egyptian doctors knew internal organs such as the heart, liver, kidneys, and gallbladder. There is even a recipe to eliminate wrinkles caused by the passage of time, which was made with urea, a substance used today in the production of face creams.

Healing through observation

Despite obtaining such a precious document, Edwin Smith never translated the papyrus, and after his death in 1906, his daughter donated it to the New York Historical Society. In 1920, the New York institution asked the renowned Egyptologist James Henry Breasted to translate it.

Thus, after a decade of hard work, the translation by Breasted allowed researchers to access the medical knowledge of the ancient Egyptians, something that until then was only known from some reliefs discovered in the temples.

Although there are several medical treatises from ancient Egypt that have come down to us, there is something that differentiates the Edwin Smith Papyrus from other medical papyri.

Unlike the magical rituals that ancient Egyptian doctors used to resort to, and which are described in the Ebers Papyrus, the Edwin Smith Papyrus states that some physicians dared to diagnose illnesses or heal injuries based on simple observation of the anatomy of corpses, something that at that time was strictly prohibited except in the case of mummification processes.

For this reason, doctors in ancient Egypt limited themselves to treating wounds, removing small external tumors, or splinting fractures, without going much deeper.

In 1938, the unique papyrus that Smith acquired in Egypt was donated to the Brooklyn Museum in New York, and in 1948 it was transferred to the Academy of Medicine in the city, where it remains today. Because of its enormous importance in the study of ancient sciences, the Edwin Smith Papyrus was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2006.

Coinciding with the exhibition, the then-curator of the museum, James P. Allen, prepared an updated translation of the papyrus that was included in its catalogue. This allowed all those interested in the medical treatments described in it to enjoy and learn from it.

Source: JM Sadurni, National Geographic