A Sicilian lawyer named Ferdinand Guidano bought in 1859 a black basalt slab that had a series of Egyptian hieroglyphs engraved on it.

He probably acquired it in some antique market in Cairo, but the truth is that its origin is not known. In 1877, perhaps after Guidano’s death, his family donated the stone to the Archaeological Museum of Palermo, where it remains to this day.

However, for many years nobody noticed it, until in 1895 the Swiss archaeologist Édouard Naville, who was visiting the museum, realized its importance.

It turned out to be a fragment of the Royal Annals of the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. Of the other six fragments that make up the original stone, five are in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (four acquired between 1895 and 1914 and the fifth in an antiquities market in 1963), and the last and smallest is part of the collection of the Petrie Museum at University College London (acquired by the famous archaeologist Flinders Petrie in 1914).

The origin of the fragments is known, neither where they were found nor by whom, except that their origin is some unidentified Egyptian archaeological site.

It has been suggested that they could come from Heliopolis (today converted into a neighborhood of Cairo), or from some temple in Memphis.

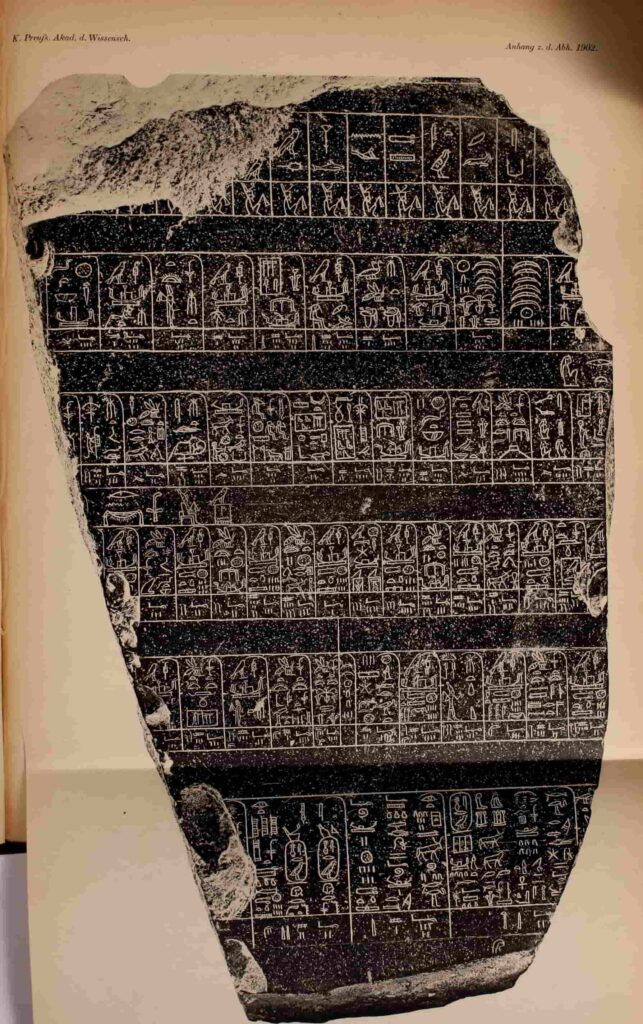

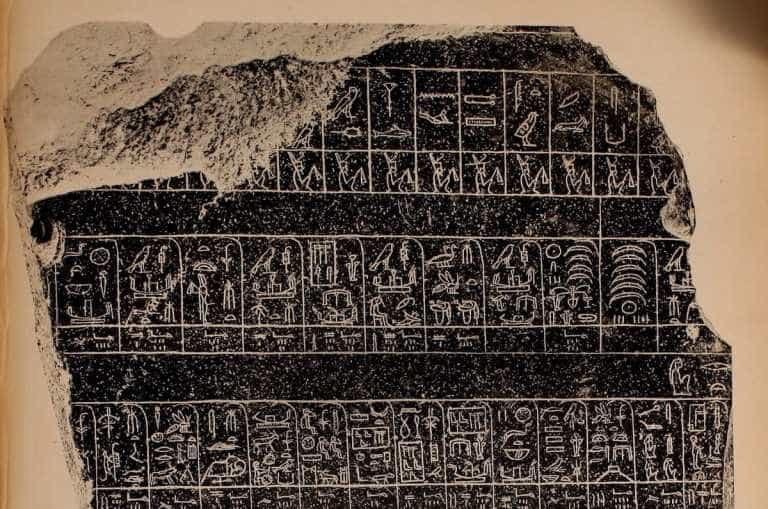

The stele to which the seven fragments belonged, known as the Royal Annals of the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt (but also known by extension as the Palermo Stone), dates from around 2430-2280 BC (some scholars think it may be later, from the 6th century BC, a copy of an older original) and, after its translation in 1902 by Heinrich Schäfer, it was found to contain a list of the kings of Egypt from the First Dynasty (3150-2890 BC) to the beginning of the Fifth Dynasty (2392-2283 BC), also mentioning the most important events of each year of the reigns. Information as spectacular as it is useful for Egyptologists.

Not only that, but it is the oldest surviving historical text from Ancient Egypt and is one of the key sources for the study and understanding of the history of the Old Kingdom period.

It is a unique document that allows historians and Egyptologists to confirm a series of hypotheses and facilitates the establishment of the ruling dynasties of Egypt.

The stela of the Royal Annals, before breaking into the seven current fragments and those that have not been found, is estimated to have measured about 60 centimeters high by 2.1 meters wide.

The piece called The Palermo Stone has an irregular shape, 43.5 centimeters high by 25 centimeters wide and 6.5 centimeters thick.

It bears an inscription in six horizontal bands with hieroglyphics (reading from right to left). The first lists the names of the predynastic kings of Lower Egypt.

In the following, the names of the kings and the royal annals (the main events of each year of reign) of the pharaohs of the first to the fourth dynasties arranged chronologically are arranged in two registers.

It begins with the records of the last year of a pharaoh of the First Dynasty whose name is not preserved, but is believed to be Narmer or Aha.

The text does not end on the front of the stone, but continues on the back, listing events during the reigns of the pharaohs up to Neferirkare Kakai, the third ruler of the Fifth Dynasty. Next to the name of each pharaoh is also the name of his mother.

In addition, the inscription also provides data and measurements of the height of the annual rise of the Nile and the consequent inundation, holidays and festivals, taxes and the census of cattle, wars, the creation of statues of gods and kings, and the foundation of temples, domains and cities.

The lists always end with the indication of the year in which the king died. However, the count of years for the successor does not begin with the assumption of the reign, but indicates the year in which he ascended the throne, that is, the year of the coronation.

The fact that it is written on both sides indicates that it was not intended to be placed on a wall, which is why it is believed that it may be one of the steles erected in the main temple of the capital (Memphis), which recorded the annals of the reigns of the sovereigns who succeeded each other on the throne of Horus.

It would therefore be a political document similar to the royal lists that were later established in other sanctuaries such as those of Abydos and Karnak.

This possibility is supported by the fact that some reigns are not mentioned on the stela, perhaps because they are considered illegitimate.

And it further confirms the testimony of Herodotus and Diodorus of Sicily, among others, who claim that the temples preserved the history of Egyptian royalty from the beginning, and that the priests could thus consult the historical records.

The pharaohs on the stela are as follows. On the obverse of the stone:

- Predynastic period: Mejet, Wadynar, Neheb, Tiu, Tyesh, Jaau, Seka

- First Dynasty: Aha, Djer, Djet, Den

- Second Dynasty: Nynetjer, Khasekhemwy

- Third dynasty: Djoser

- Fourth dynasty: Seneferu

On the reverse of the stone:

- Third dynasty: Huni

- Fourth dynasty: Shepseskaf

- Fifth dynasty: Userkaf, Sahura, Neferirkare