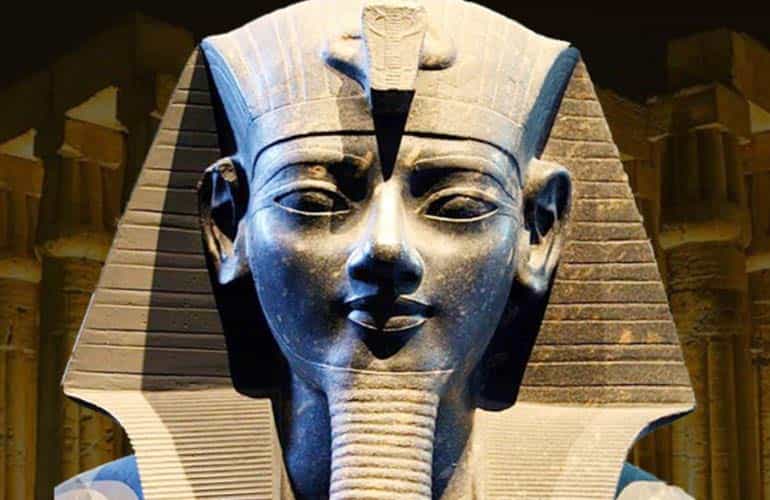

Amenhotep III, also known as Amenophis, was the ninth ruler of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, reigning approximately from 1390 to 1352 BC. During his nearly 40-year rule, he stabilized the prosperous economy he inherited and encouraged remarkable artistic achievements that symbolized Egypt’s grandeur. His reign, positioned at the height of the New Kingdom, firmly solidified Egypt’s power and prestige across the region.

Under Amenhotep III, Egypt engaged more intensively with major contemporary powers of the Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. This increased engagement was a legacy of Pharaoh Ahmose, founder of the 18th Dynasty, who had expelled the Hyksos invaders from the Near East and initiated Egypt’s imperial expansion.

In the realm of international relations, there were two distinct groups: the large empires (such as Mitanni, Egypt, Babylon, Hatti, and the Mycenaean kingdoms) and smaller regional states that acted as buffers, easing the political and territorial frictions among the great powers.

Among the prominent empires, Egypt’s primary rival was Mitanni, an Indo-European kingdom based in Upper Mesopotamia. This powerful state, led by a warrior aristocracy skilled in chariot warfare, took shape in the mid-2nd millennium BC, forged through the integration of various ethnic groups over centuries of gradual settlement.

The rise of Mitanni’s empire was fueled by a unique charioteer culture and innovations in lightweight chariot design and horse training. This advanced military technology not only supported their expansion but also spread across the kingdoms of the ancient world, reshaping warfare in the region.

Upholding the Balance of Power

In the ancient world, multiple formidable kingdoms shaped the political landscape. The Kassite dynasty reigned over Lower Mesopotamia in Babylon, while a formidable force was rising in Anatolia and northern Syria—the Hittite Kingdom of Hatti.

The Hittites, set to become a central force in the Near East for the next 150 years, began pressing on Mitanni’s northern borders. Meanwhile, in the Peloponnese and the Aegean, the Mycenaean city-states emerged as influential warriors and traders, maintaining robust ties with eastern kingdoms.

In this delicate balance, diplomacy played a crucial role in averting war and sustaining trade. Diplomatic exchanges, such as those documented in the Tell el-Amarna letters, provide insight into how these relationships operated.

The rulers of the dominant empires, often referred to as “great kings,” corresponded as equals, calling each other “brother.” These bonds were strengthened through arranged marriages, gift exchanges, and the sharing of skilled artisans and images of healing deities.

In contrast, the “great kings” had a hierarchical relationship with the rulers of smaller principalities acting as buffers between the larger empires. These minor kings, in exchange for loyalty and tribute, received protection and were allowed to continue ruling their domains.

During Amenhotep III’s reign, the international stage was unusually peaceful. His grandfather, Amenhotep II, had previously forged an alliance with Mitanni in response to the expanding Hittite influence in northern Syria.

Amenhotep III led only one military expedition to Nubia in his fifth regnal year, choosing instead to prioritize strong ties with Mitanni. This was not so much a pacifist approach as it was a strategy to preserve a mutually beneficial status quo.

As Hatti expanded at Mitanni’s expense, evidence suggests that Egypt sent emissaries to various Mycenaean kingdoms, which strengthened commercial relations. This was an era of unmatched prestige and influence for Egypt on the international stage.