In 1897, British archaeologists James Quibell and Frederick W. Green were excavating the ruins of Hierakonpolis (known as Nekhen in ancient Egypt and present-day Kom al-Ahmar), the capital of Upper Egypt until the end of the Protodynastic period (approximately between 3500 and 3100 BC).

There, beneath the temple of Horus, they discovered a large repository of votive objects dating from the late Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BC), but also containing much older objects that had been moved there later.

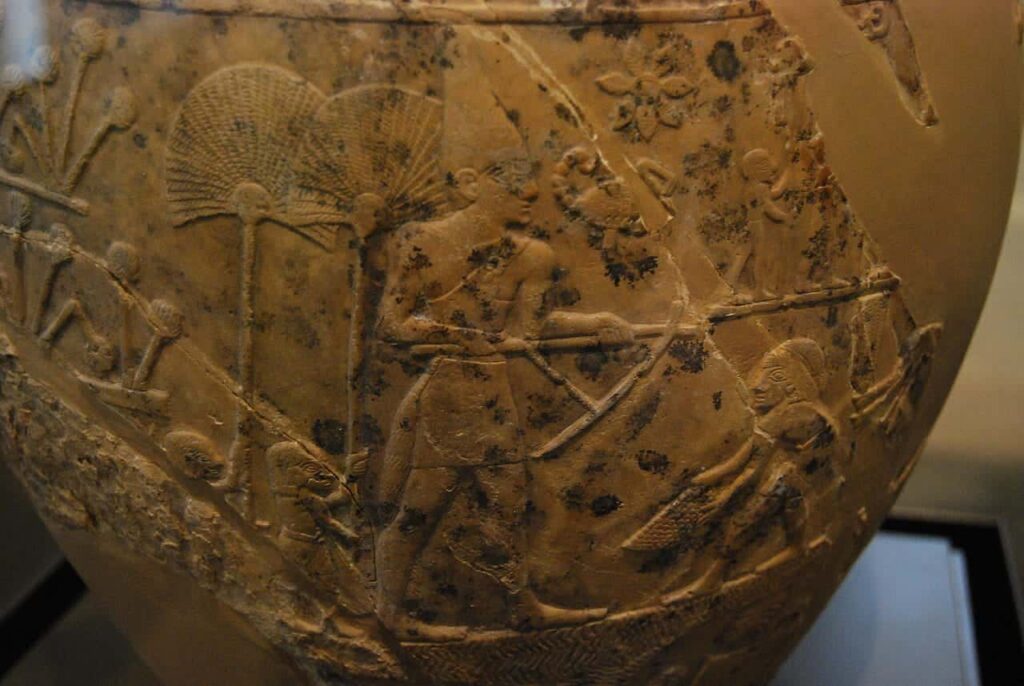

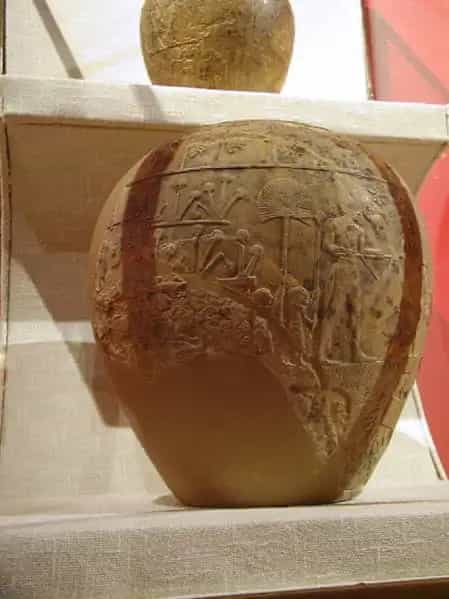

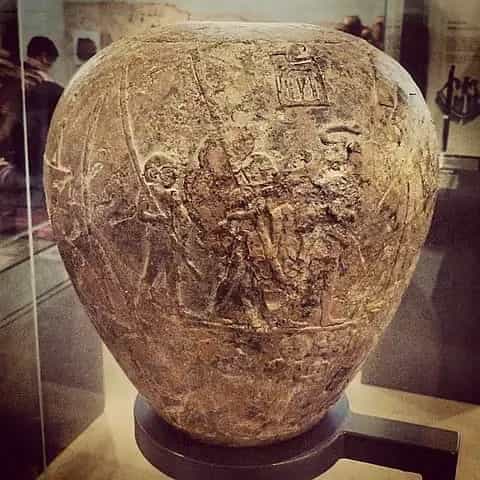

One of these objects was a limestone macehead about 32.5 centimeters tall, depicting a large pharaoh wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt. Next to him is an engraved image of a scorpion representing his name. The macehead is a ritual object, about five times the size of a functional mace.

The king is shown standing with a bull’s tail next to a watercourse, possibly a canal, holding a hoe symbolizing the ritual opening of dikes after the flooding of the Nile or a ditch for the foundation of a temple or city.

This is the oldest evidence of this rite, which would continue in ancient Egyptian iconography until Greek domination. The king faces a man with a basket throwing seeds to the ground, another carrying a huge bundle of sheaves of grain, and others carrying banners.

Some men appear to be performing tasks in the canal, while in the rear of the king’s entourage are papyrus plants, a group of women (perhaps dancers), and another small group of people with their backs to the pharaoh. In the upper right part of the king’s depiction is the dog Khenti-Amentiu, the god who protected the necropolis of Abydos.

In the upper register, a row of banners appears with Rekhit birds hanging from them. Lapwings were originally used to refer to the inhabitants of the delta or Lower Egypt by the inhabitants of Upper Egypt.

All of this is interpreted as evidence of the conquest of Lower Egypt by a king named Horus Scorpion II who ruled around 3075 BC. He is better known as the Scorpion King to distinguish him from another older king with the same name who ruled Upper Egypt around 3250 BC and about whom not much is known.

The macehead, which is now in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, United Kingdom, would be one of the oldest depictions of an Egyptian king, and is the only visual evidence of the existence of the Scorpion King, of whom no other historical information has been found. It is also considered the oldest macehead found to date, dated around 3075-3050 BC.

The exact burial location of the Scorpion King is unknown. Researchers believe that his tomb may be either the so-called B50 in the Umm el-Qaab necropolis in Abydos or the so-called HK6-1 in Hierakonpolis.

The former is an almost square chamber divided into four rooms by a simple mud wall. The latter measures 3.5 by 6.5 meters, has a depth of 2.5 meters, and is reinforced with mud. In both, several ivory plates with scorpion figures have been discovered.

At the end of 2020, researchers from the University of Bonn, together with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, deciphered the world’s oldest place-name sign, a hieroglyphic inscription found in the Wadi el Malik east of Aswan that reads “King’s Domain Scorpion of Horus,” which is believed to refer to this same king.

Some Egyptologists, such as Bernadette Menu, believe that since the Egyptian kings of the First Dynasty seem to have had multiple names, Scorpion was the same person as Pharaoh Narmer, but with a different name or additional title. In fact, both seem to have been contemporaries, and the art style of the macehead bears intriguing similarities to a similar one from Narmer.

Others, such as TH Wilkinson, Renée Friedman, and Bruce Trigger, believe that the Scorpion King was the ruler of a minor kingdom that was later conquered by Narmer to unify ancient Egypt.

Source: Guillermo Carvajal, labrujulaverde

Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt

Toby AH Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt