Deir el-Medina is in the deserted hills on the west side of the Nile, near the Valley of the Kings and 4 km away from the Temple of Amun in Thebes.

In Deir el-Medina, there was a large complex of tombs belonging to dignitaries and high officials of the pharaonic court. Among them, the tomb of Nebamun stood out for the exquisite and sumptuous way its walls were painted.

The tomb is missing today, but the frescoes were acquired by the English in the 1820s and are now preserved in fragments in room 61 of the British Museum.

Dated to around 1350 BC, the tomb not only fulfilled its function of the burial of Nebamun and his wife but also served as a funerary chapel, which remained open so that family and friends could enter to celebrate the festivals and commemorative ceremonies established in honor of Nebamun and his wife.

Nebamun was a middle-ranking official scribe and grain counter at the Temple of Amun in Thebes, which allowed him to procure a grave worthy enough to enjoy his life in the Hereafter.

The wonderful frescoes in his tomb demonstrate an idealized vision of the ancient Egyptian paradise and how Nebamun wanted to be remembered as rich, healthy, and powerful.

The main chamber was dominated by a small-seated statue of the deceased and his wife, placed in a niche in the back wall.

The paintings in this chamber represented Nebamun hunting on a boat on the Nile on the one hand and a paradisiacal garden on the other.

The hunting scene is extraordinarily rich in compositional and color nuances. The motley of birds taking flight among the lotus flowers is a metaphor for the abundance with which the protagonist was favored in life.

But hunting here is not related to providing food for survival; instead, it is sporty and loaded with more subtle connotations.

After all, hunting is a symbolic struggle of man to dominate the wild elements of nature and demonstrate his supremacy. Among the royalty and noble classes of ancient Egypt, it became a kind of simulation through which power was flaunted to subdue enemies.

As for the paradisiacal garden, it is the same as the gardens of the noble palaces of the Eighteenth Dynasty, corresponding to the historical period in which Nebamun lived.

In the center, there is a pond full of fish and birds (again a symbol of abundance), surrounded by many flowers, shrubs, and rows of fruit trees, such as palms and sycamores.

In the upper right corner, the goddess Nut offers sycamore figs and jars of wine or beer to Nebamun, whose figure is missing from this fragment because it was destroyed. On the left, some hieroglyphs name him as the garden’s owner.

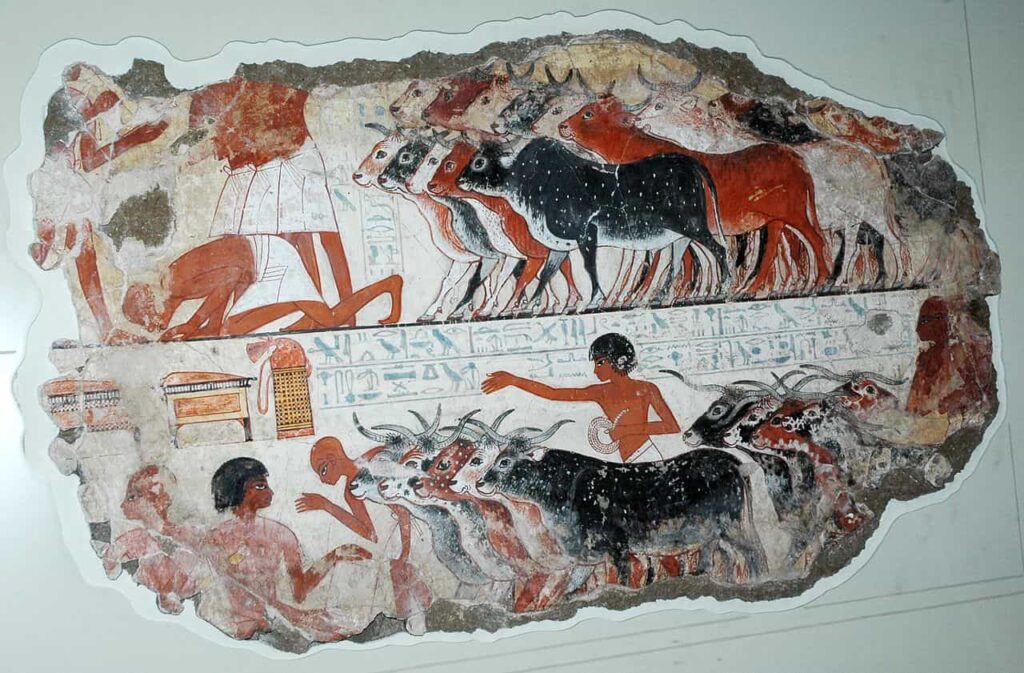

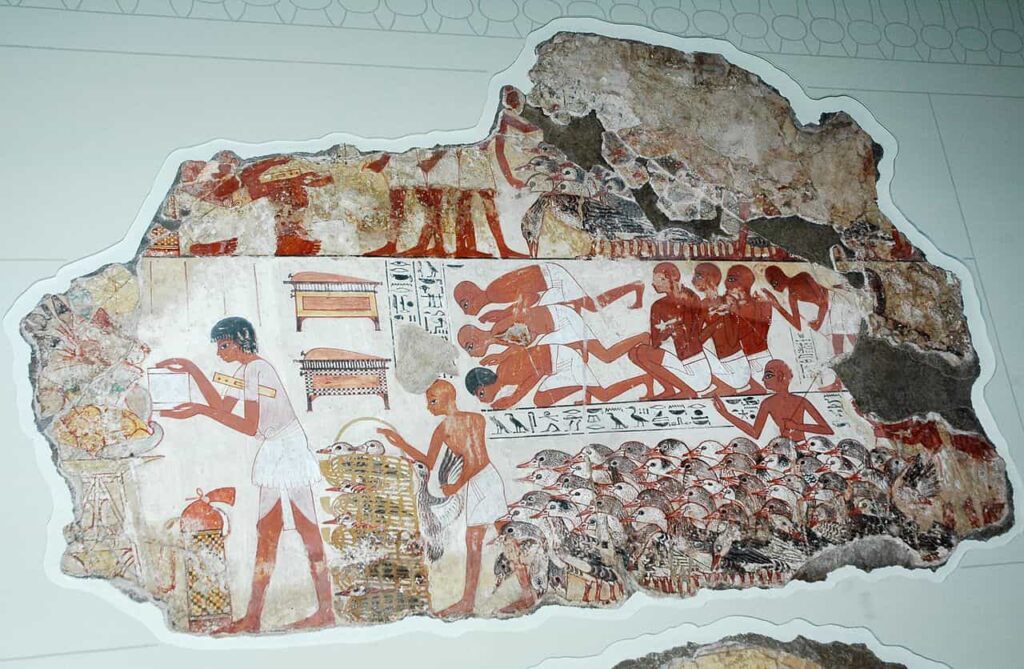

The scenes that decorated the antechamber walls dealt with more prosaic subjects. Fragments contain groups of animals arranged for counting and other administrative activities related to Nebamun’s profession.

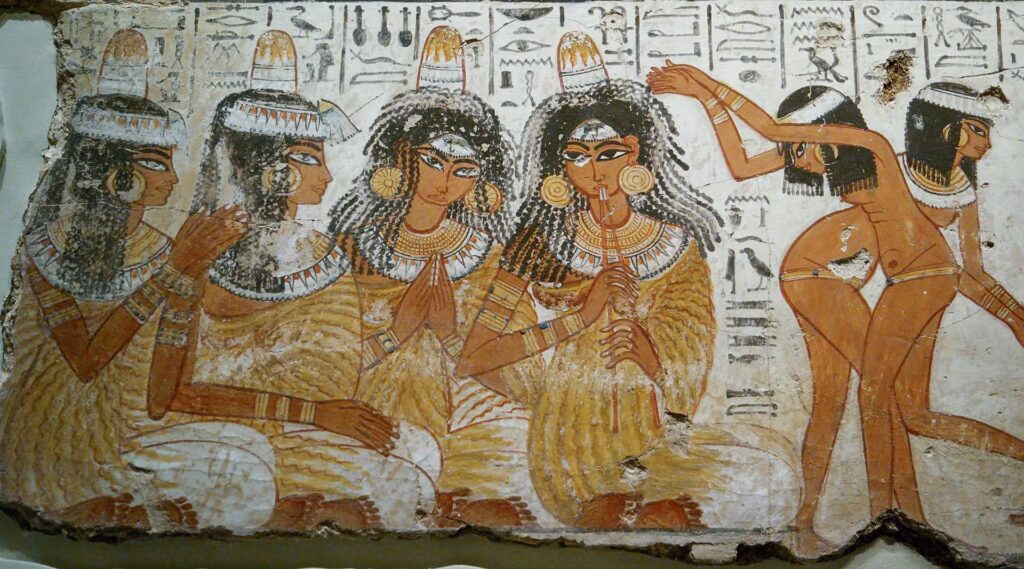

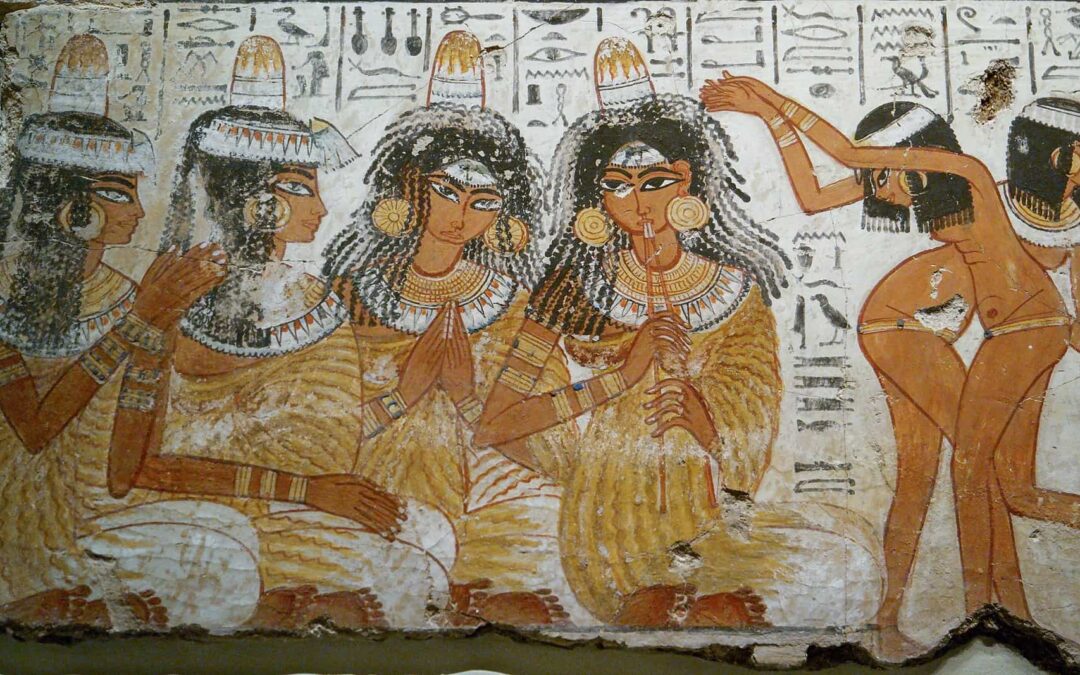

Although the most beautiful parts are those that represent various moments of a lavish banquet in honor of the deceased, this occupied an entire wall of the antechamber.

Nebamun’s family and friends are seen there, served by naked maids and waiters. Married couples sit in pairs in the upper frieze, and single girls turn to talk to each other in the lower frieze.

All are richly dressed and are entertained by musicians and dancers during the meal.

The instrumentalists sit on the floor, clap their hands, and play a double flute to liven the banquet. This group forms one of the best-known paintings in the History of Universal Art.

The two girls sitting in the center stand out, without a doubt, as they are represented from the front and not in profile, as was usual in ancient Egyptian paintings.

The decoration of the tomb of Nebamun is a clear example of the importance the ancient Egyptians attached to death and the afterlife in accordance with their religious beliefs. Both were a source of concern throughout their earthly life.

Among the privileged classes, this translated into the deliberate will to properly build and prepare a tomb that would be splendid to properly enjoy the Hereafter.

Consequently, art was used as a powerful tool to represent such desires. By means of beautifully worked paintings and hieroglyphs, the best virtues of the deceased were described, justifying the right to eternity, and procuring the necessary favor to enter paradise. That was Nebamun’s intention when paying for the rich ornamentation of his tomb.