The pyramids and temples for which the Pharaonic civilization is known were not built by slaves, whose presence in the Nile Valley was virtually nonexistent. On the contrary, they were erected by individuals who served the pharaoh and received a salary.

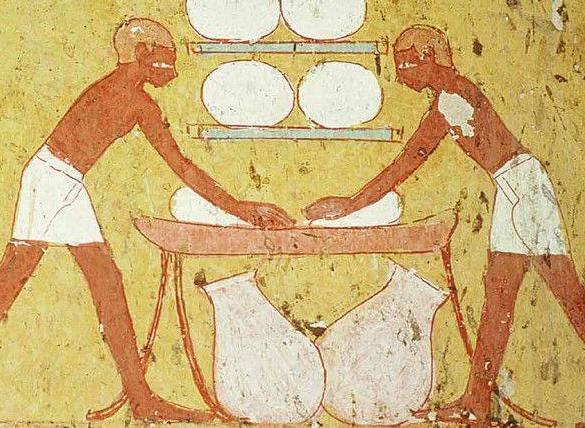

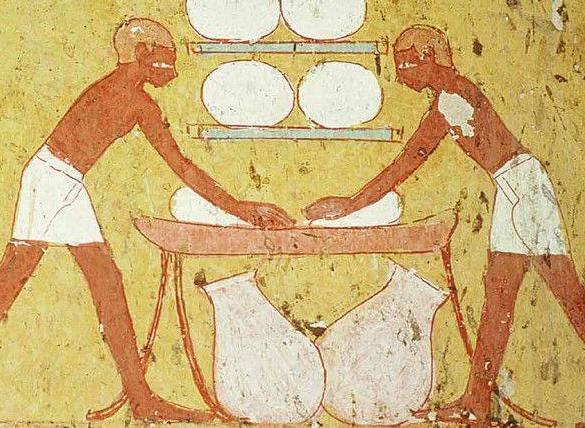

Similar to soldiers, priests, and other temple workers, these individuals were compensated with “rations” instead of money – as the ancient Egyptians did not use currency – specifically consisting of bread and beer, which formed the fundamental components of their diet.

The ration comprised ten daily units. Based on documents discovered at the Nubian fortress of Uronarti, we know that soldiers stationed along Egypt’s southern border received rations spanning weeks (since ancient Egyptians counted in ten-day periods). For such a duration, their ration included 60 units cooked from 2/3 heqat of northern barley (2.25 kg) and 70 units cooked from 1 heqat of wheat (3.75 kg).

These quantities provided them with approximately 2,136 calories per day, which were evidently insufficient. Therefore, cereals could only constitute a portion of their compensation, supplemented by rations of beer and some animal proteins, essential for enabling these men to carry out their duties patrolling the desert.

Pyramid Builders: Meat Consumption

The presence of these protein supplements is confirmed in the city of the Pyramid builders at Giza. Approximately two hundred thousand bones and fragments belonging to fish, birds, and mammals have been discovered thus far. Among the latter, pigs are the least common, while young male sheep, goats, and cows are the most abundant.

While bakeries have been uncovered in the city of the pyramid builders, the same cannot be said for stables, suggesting that housing and breeding of animals were carried out elsewhere.

Production centers, like Kom el-Hisn in the Delta, focused on the breeding and fattening of cattle from the Old Kingdom onwards, with these animals later transported to Giza for consumption.

In addition to meat, they also received rations of wheat and barley transformed into bread and beer. This ensured they reached over three thousand daily calories necessary to perform the demanding tasks required of them.

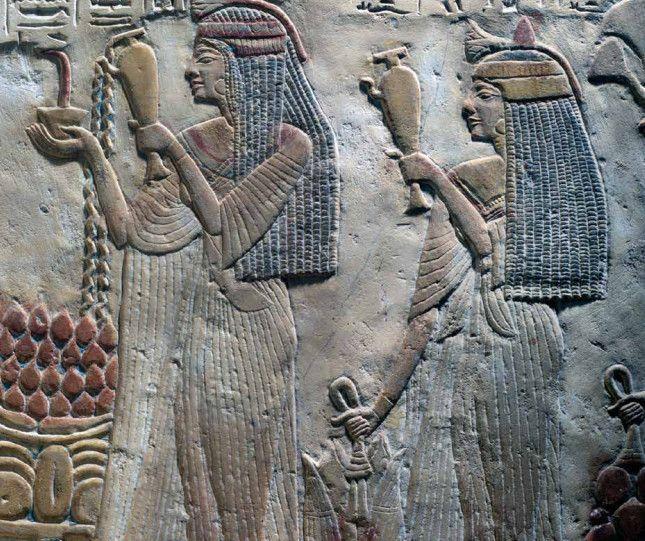

Supplementary rations for strenuous labor were a known practice, as evidenced by the decorations in the tomb of Antefoker (Thebes, XII dynasty). Another form of payment by the Pharaoh was the distribution of temple offerings, which occurred twice daily and in large quantities.

To grasp the scale, consider that the Mortuary Temple of Neferirkare (V dynasty) required 660 birds per month (8,000 annually) and 30 oxen per month (360 annually).

After spending some time on the altar to nourish the gods with their essence, the food was then distributed among all temple workers, not just the priests.

Naturally, distribution followed a strict hierarchy, with priests receiving larger portions compared to those dedicated to tasks like skinning oxen. Mastery of such distribution was a fundamental skill for scribes, crucial for the efficient functioning of Pharaonic administration.

Source: Historia y Vida