Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley is casting doubt on what we thought we knew about Tutankhamun. The image typically held of the pharaoh, whose tomb was discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter, is not very impressive.

Due to his young age – he died at 18 or 19 – and physical damage to his mummy’s feet, it has been assumed that he was an incapable and invalid king, manipulated by court figures who may have even assassinated him.

However, Tyldesley challenges these ideas in her book Tutankhamun: Pharaoh, Icon, Enigma. She argues that Tutankhamun may not have been disabled, as previously thought.

Firstly, she suggests that the damage to the mummy’s foot could have been postmortem or even caused by a mistake during the mummification process.

Furthermore, the canes found in Tutankhamun’s tomb may not have been used to support him. Tyldesley notes that “the cane was a symbol of authority carried by elite men, and it does not have to indicate an illness or a problem walking.” Additionally, the footwear depicted in his grave goods does not suggest that he had any foot problems.

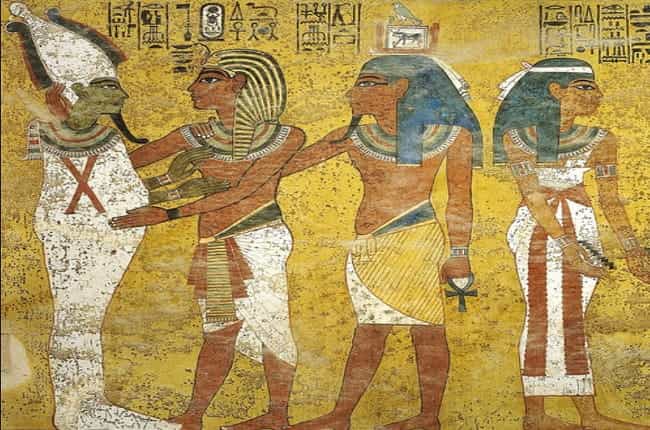

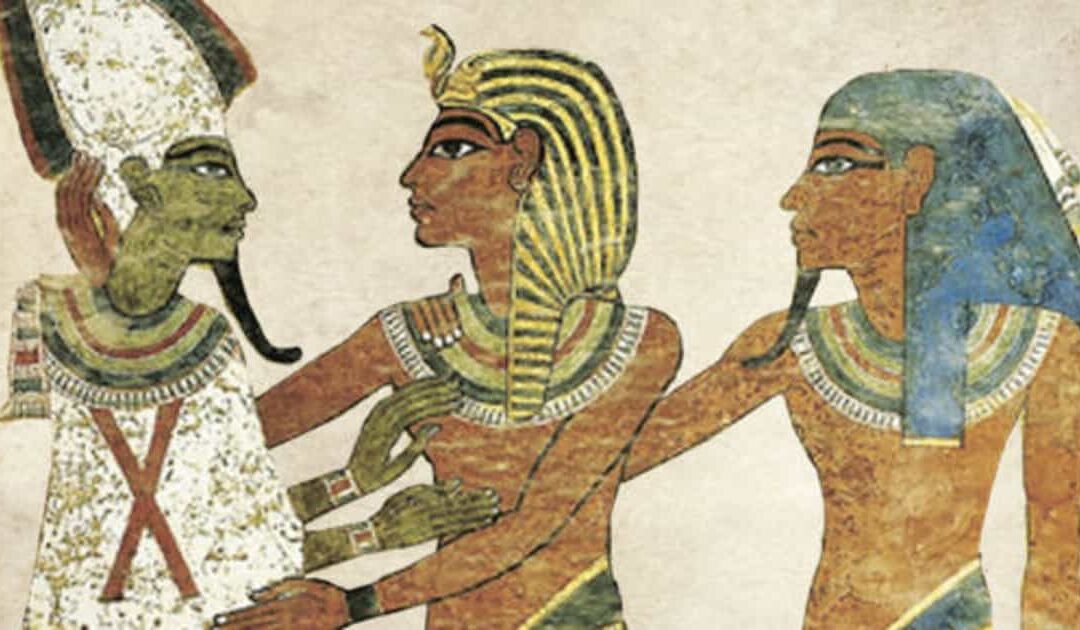

Instead, the author suggests that the pharaoh may have been perfectly healthy. Images of Tutankhamun hunting ostriches in the desert while riding his chariot indicate that he could not have had mobility issues. This was an activity typical of the elite that he would not have been able to carry out if he had any physical limitations.

Moreover, Tyldesley supports one theory about his death, that of a chariot accident, as proof that the pharaoh was in good health. This activity required training and good physical condition. However, it should be noted that these hunting scenes may not necessarily have accurately portrayed reality.

Joyce Tyldesley also questions the common portrayal of Tutankhamun as a puppet king. While it is true that his advisers held the reins of the kingdom when he ascended the throne at the age of eight or nine, the author doubts that he still had no power at the age of 18 or 19.

Furthermore, she suggests that the pharaoh may have agreed with the decision to reverse the monotheistic policy of his father, Akhenaten, as a guarantee of recovering the stability of the kingdom. This would be a sign of his good judgment in not wanting to repeat the errors of the “heretic pharaoh.”

The Enigmas of Tutankhamun and His Tomb

The author also addresses some of the mysteries that remain in discussion regarding the child pharaoh and the tomb discovered by Howard Carter and his team in November 1922, an event that was celebrated last year to mark the centenary of the discovery.

One of the most persistent doubts is about his immediate family, particularly his mother, Queen Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s Great Royal Wife.

Historically, she has been presented as a very important queen who may have even ruled as pharaoh between the death of Akhenaten and the enthronement of Tutankhamun.

But Joyce Tyldesley suggests that Nefertiti may not have had such a prominent role since she was “not of royal blood by birth.”

Instead, the author highlights the roles of Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamun’s wife, and Meritaten, his older sister. Both were of royal blood, daughters of Akhenaten, and therefore, the author believes that they could have exerted greater influence at court. As for Nefertiti, she believes that she was simply “an important queen in a family of important queens.”

Another mystery that Tyldesley tackles is the hypothesis put forward by Nicholas Reeves that Tutankhamun’s tomb still hides secret chambers.

On this, the author does not believe “that there is enough evidence to suggest that there are completely finished rooms,” although she maintains that it is possible that they would have tried since the pharaoh’s tomb was hastily arranged due to his early death:

“No, I would be surprised if the tomb builders, in adapting the burial site for Tutankhamun (a logistical nightmare), would have tried to create more chambers by opening them from the burial chamber. The remains of these unfinished chambers (ghost door profiles) may well be evident beneath the plaster.”

Tyldesley believes that “the only way to solve this problem once and for all would be to drill a hole in the wall and insert a camera, but that would be a very destructive method and unlikely to be done.”

In addition, she maintains that Carter possibly already verified at the time that there were no secret chambers using pins. So, for now, the tomb of Tutankhamun continues to keep the last mysteries of him.

Source: Abel GM, National Geographic

Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley, “Tutankhamun: Pharaoh, Icon, Enigma”