During the third dynasty, the architect Imhotep had the brilliant idea of enlarging the mastaba of Pharaoh Djoser to make it the first pyramid in history.

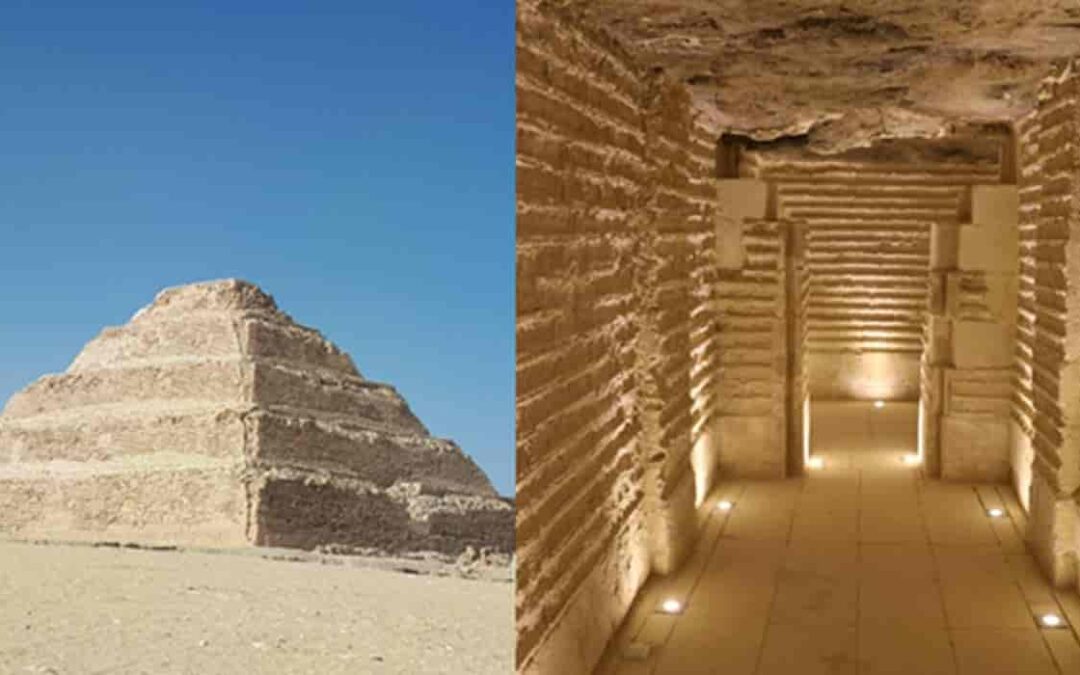

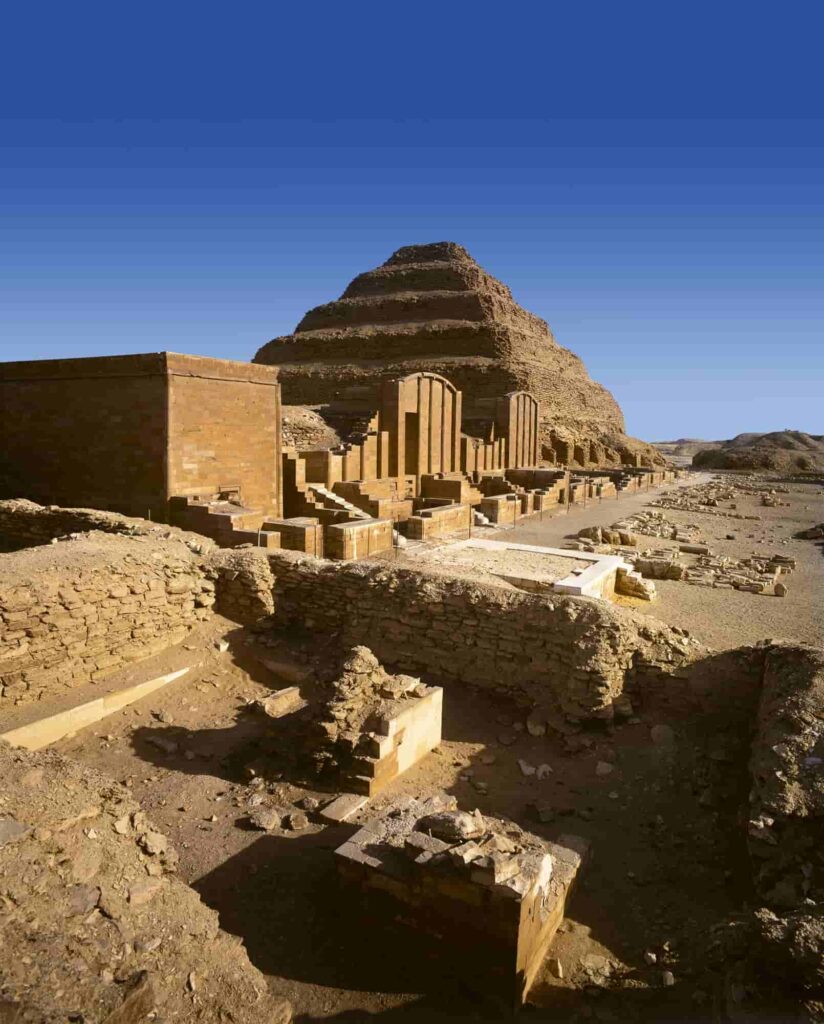

Build a monumental stairway to heaven: such was the intention of the architect Imhotep when he conceived the famous pyramid of Saqqara. At 60 meters high, it was the greatest construction that the Egyptians had undertaken up to that time; only surpassed almost a hundred years later by the great pyramids of Giza.

Such dimensions were at the height of the purpose pursued by its creator: to allow his lord Djoser, once buried there, to ascend the six steps of the construction to meet the god Ra, without appearing before the court of Osiris, the god who judged the souls of the deceased.

Actually, the one at Saqqara cannot be said to be a pyramid, and it is not even entirely accurate to speak of a “step pyramid.”

In fact, as the French archaeologist and architect Jean-Philippe Lauer, who spent 75 years studying the site, demonstrated, the building did not start from a complete initial project, but was the result of a series of successive modifications.

Originally it was a mastaba, a large flat-roofed brick structure with which pharaonic tombs were covered since the first dynasty.

The Saqqara mastaba had a square plan, 63 meters on a side, and reached a height of 8 meters. Its core, made up of stones joined together with a clay mortar, was lined, up to a height of 2.60 meters, with polished blocks of the finest Egyptian limestone from the neighboring quarry of Tura, which gave the building an immaculate appearance.

One might wonder why the builders did not cover all of the sides or even increase their elevation. Beyond mere technical considerations, it is an example of the particular sensitivity of the ancient Egyptians, of their sense of the eternal: the uncoated upper section would remind us that, below, the beauty of the perfect remained unchanged forever.

The mastaba received a second limestone block cladding, which increased the sides of its base to 71.50 meters, but neither did its height increase, since this second cladding was 65 centimeters from that reached by the initial mastaba.

The birth of a pyramid

During the reign of Djoser a new extension was carried out. The mastaba was lengthened 8.36 meters to the east, thus blocking the entrances of eleven wells, 33 meters deep, in front of the eastern face of the tomb.

Each well led to a gallery thirty meters long, which ran under the monument. The first five galleries, lined with wooden planks, turned out to be tombs of the king’s relatives, while the remaining six were warehouses.

The mastaba, with a rectangular base, then measured 71.50 by 79.86 meters and maintained its initial height of 8 meters.

It was probably at this time that the architect Imhotep decided that the tomb of Djoser should take the form of a great staircase by which the deceased king would ascend to heaven.

To do this, he expanded its four sides with stone blocks up to 2.90 meters thick. On this base, three gigantic steps were raised, in the shape of mastabas, which raised the structure to 42 meters in height.

In this way, from the superposition of smaller and smaller mastabas, the first stepped pyramid in the history of mankind had been born.

But Imhotep decided to enlarge his work even more, so that it was visible from the distance of the immense palm grove of Memphis. Thus, two more steps were added, expanding the existing sides to the north and west. The final pyramid measured 109 by 121 meters at its base, with a height of nearly 60 meters.

The secrets of the pyramid

In front of the unique building designed by Imhotep, the step pyramid of Saqqara also had an infrastructure no less complex and impressive.

A maze of galleries and chambers pierced the terrain to create a veritable palace of eternity, the destination of King Djoser’s life in the Hereafter.

The walls of all these rooms were lined with greenish blue faience, evoking the freshness of the green landscape that the King of Egypt should enjoy forever.

The nerve center of the construction was, of course, the pharaoh’s burial chamber. It was accessed by an open road, which started from the temple located next to the north face of the pyramid.

A descending flight of stairs gives way to a horizontal roof tunnel that goes deep into the basement of the pyramid and ends in another long flight of stairs.

Finally, this section ends in a square well measuring 7 meters on a side and 28 meters deep, at the bottom of which an authentic vault of pink granite blocks was built to house Djoser’s mummy.

A hole one meter in diameter, made in the upper part of this colossal box, allowed the entrance of the wooden coffin with the royal mummy. Later, a granite plug sealed the largest sarcophagus ever built in ancient Egypt.

At the same level as this chamber, and next to the angles of the shaft, four galleries were excavated. The tunnels forked, branching out and taking on the appearance of huge combs.

Three of these labyrinthine corridors housed the grave goods, while the one that started on the east side was the most intimate chamber of the Ka of Djoser, his life force.

The four chambers excavated in this last maze feature beautifully decorated walls. Encased in the limestone, some glazed plates, with exquisite blue-green, imitate vegetable tapestries.

The chamber to the east is the most interesting for its artistic elaboration. Along with vertical loopholes, like tiny windows, three mock doors show King Djoser in bas-relief officiating the rites of his rank, such as the visit to the sanctuary of Horus of Edfu (perhaps the future temple of Edfu).

Source:

Maite Mascort, National Geographic

History of the pyramids of Egypt. JM Parra. Ed. Complutense, 2009.

All about the pyramids. Mark Lehner. Destination, Barcelona, 2003.