The idea of beauty that the ancient Egyptians had is evident to us thanks to sculptures and frescoes, but also to jewels and artifacts. Its objective? The eternal seduction.

Throughout 3,000 years – thirty centuries! – of existence as a people, the ancient Egyptians hardly changed the way they dress, comb their hair or adorn their bodies. To speak of Egyptian fashion is not, then, to speak of trends, but rather of traditions.

Not surprisingly, princes, scribes, priests and everyone who could afford mummification lived their lives with an eye on eternity. An immortal had to bet on the classic, there was no room for passing fashions in his grave goods.

Even so, without sinning as fashion victims, the ancient Egyptians worshiped beauty. They took care of their hygiene and their personal appearance with extreme flirtation, both men and women.

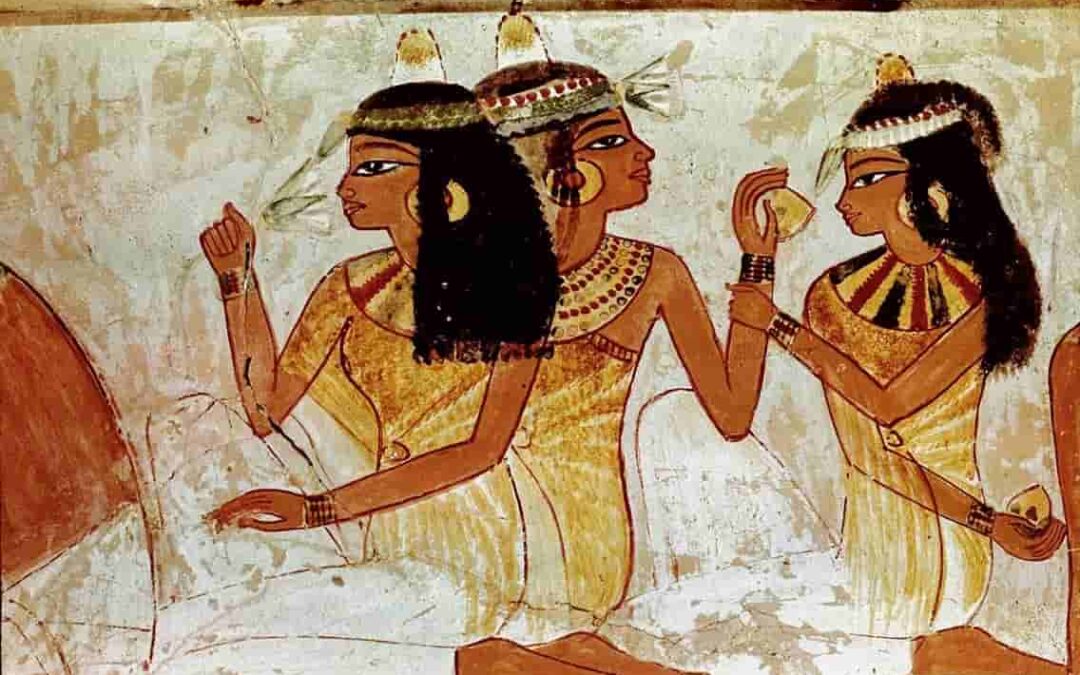

In the paintings and reliefs they have left us there is no place for ugliness, decadence or old age. Sagging breasts and flabby flesh are not abundant either: the bodies of ancient Egyptian art are flexible, firm and slender.

To accentuate their slenderness, the artists did not hesitate to alter the natural proportions, lengthening the legs and reducing the actual size of the buttocks, an aesthetic ideal like that of the 21st century.

Harmony and dignity are the dominant notes even on the rare occasions when people with malformations are depicted.

In 2007, an anonymous mummy from the Valley of the Kings, found by Howard Carter in 1903 and since forgotten in the cellars of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, was identified as Queen-Pharaoh Hatshepsut. It corresponded to an obese woman in her sixties.

Her initial discoverers, without a hint of gallantry, had described her “overweight woman” in the catalog.

Nothing to do with the Hatshepsut of statues and sphinxes, a graceful girl in a man’s headdress, frozen forever in the prime of life.

Queens, especially the Queen Consort, or Great Royal Wife, were to be beautiful by decree. Whether they were or not, they received official titles such as “queen of charm”, “the one with a beautiful face”, “the enchantress, who satisfies the divinity with her beauty” or “the one who permeates the palace with the scent of her fragrance”.

Ancient Egyptian Clothes

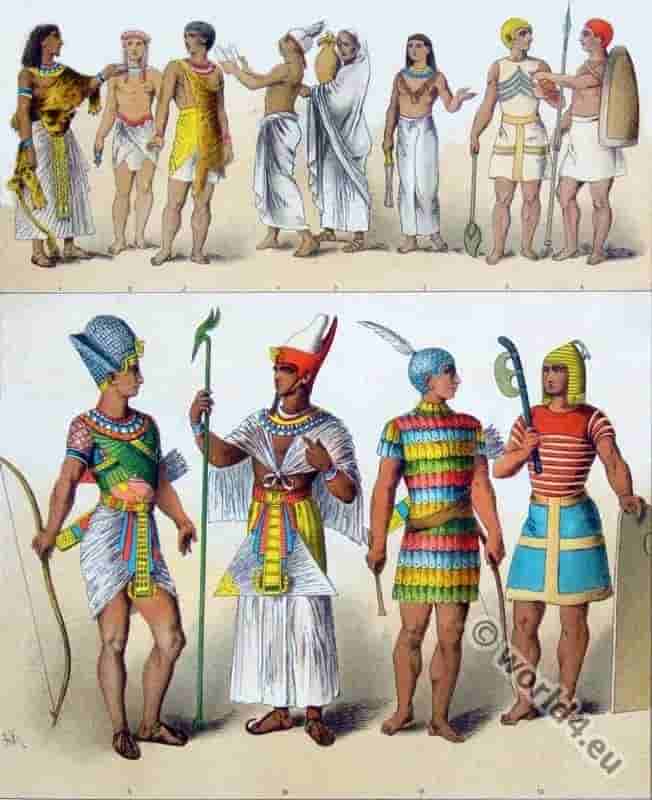

Clothes are an extra, a sign of distinction. You don’t dress the same on a weekday as on a holiday. The quintessential male garment is the schenti, a skirt made from a short fabric, the crossed ends of which are tucked into the belt and tied with a front knot.

During the Old Kingdom, the nobles wear it every day, but lower-class men reserve it for special occasions, such as going to the temple, visiting distant relatives, or celebrating the end of the harvest.

The wardrobe becomes more complicated as you move up the social ladder. A piece is added that protrudes from the front or the edge is rounded. In events that require extreme elegance, the schenti is adorned with a brooch or a piece of golden fabric.

At the end of the Old Kingdom and the beginning of the Middle Kingdom (dynasties 6th and 7th, 24th-20th centuries BC), the schenti is lengthened to the calves, and sometimes an apron decorated with horizontal or vertical stripes is added. The first robes also appear.

In the Middle Kingdom a fine long skirt is added over the skirt and a short pleated cloak is popularized. The New Kingdom (c. 1500 BC) definitively put an end to the nakedness of the torso, which is covered with tight or wide tunics, to which sleeves and pleats are progressively added.

The schenti also evolves. The skirt is shortened at the front and lengthens at the back. There are even puffed models. And not even the pharaoh is free of these new sophistications.

As a sacred character, the king usually wears only the classic skirt, adorned with a bull’s tail that emphasizes his power, and a nemes (striped scarf) on his head.

This ceremonial sobriety will remain adulterated from the 18th dynasty, in which folds, transparencies, sleeves and other trifles also slip into royal iconography.

Bread and flax

Despite not being strictly necessary, or perhaps precisely because of this, in the last dynasties the dress became important even for the popular classes.

In 1123 BC., the workers who worked in the tomb of Ramses III staged the first known strike in history to protest the delay in the payment of their wages, which were paid in kind.

The clothes were on their list of complaints: “We have come here driven by hunger and thirst,” they cry out. “We have no clothes, no fat, no fish, no vegetables.”

The fabrics were not only used for covering, but also as a bargaining chip, and their value depended on the quality of the linen with which they were woven. There were four categories.

If the stems were harvested while the plant was still young, the resulting tissue was of better quality.

Although garments made with goat hair, sheep wool and palm fibers have been found, linen was the star fabric. Lightweight and breathable, it was ideal for the sweltering Egyptian climate.

Cotton could have served the same function as well, but it was not introduced until the 1st century AD, when the pharaohs were already a memory. The silk would still take three more centuries to arrive.

Despite its advantages, linen had a drawback: it was very difficult to dye. That is why most of the garments were completely white or had, at most, some detail or colored border. In some sarcophagi completely stained red bandages have been discovered, but these are exceptional cases.

The women’s wardrobe was no less sober than the men’s, nor was it much more demure. The most common and repeated model for three millennia is a tubular tunic, seamless, close to the body like a glove, which enhances every curve of the female body from the ribs to the ankles.

Except for models with wide straps, this design leaves the breasts exposed. Goddesses always wore this type of tunic, which never went out of style, but mortals, especially the wealthiest, were inventing variations.

At the end of the Old Kingdom appear the gathered tunics with sleeves and a type of fitted shirt that leaves the right shoulder exposed. Sometimes these garments have embroidery on the hem.

Creams for everything

Surely, a camphor-based fragrance would not enjoy much success in today’s perfume shops, but Egyptian cosmetics had a practical component, as well as an aesthetic one.

The camphor served to drive away the insects; ointments, to restore elasticity to sunburned skin; and kohol, which had an antiseptic effect, to protect the eyes from possible conjunctivitis.

There were formulas for just about everything, from preventing wrinkles to curing baldness. There was even a recipe to make a rival lose her hair (literally), a curse that, fortunately, had an antidote.

Men and women shaved and waxed, exfoliated their skin with honey and sea salt, hardened their muscles with natron powder, applied masks based on frankincense, moringa oil, beeswax and calamus, and hydrated with all kinds of fatty substances, including olive oil, a very expensive and imported product.

All these potingues could be kept in exquisite alabaster, basalt or terracotta jars and in carved wooden boxes, and they were applied with the help of sticks, spatulas and spoons.

The containers were usually decorated with animal shapes or geometric motifs.

Washing, purifying and waxing were daily acts that were not without religious significance. Priests were required to bathe at least twice a day, and took their aversion to hair to the extreme of fully plucking eyebrows and eyelashes before sacred rites.

In addition to blades and tweezers, picturesque hot plasters were used, made from “boiled and crushed bird bones, sycamore juice, gum, and cucumber.”

The ingredients of the perfumes were much more common: cinnamon, lotus flower, iris, rose, mint, incense … Not so its use.

Essential oils were extracted from them or soaked in fat to make ointments, a common technique in other ancient cultures.

But in addition to applying these essences to the skin, the ancient Egyptians made with them curious cones of fat that the most elegant were placed on the head, on top of the wig.

A good perfumed cone on the forehead was a sign of good taste, the indispensable complement of any lady invited to a posh party.

Surely the heat was dissolving the fat of these preparations and thus spreading their aroma in the air.

Ancient Egyptian jewelry

The popular classes also did not renounce the pleasure of adorning themselves with jewels. Since materials such as gold and precious stones could not be afforded, they turned to ceramics, bone, stone, and natural flowers.

Egyptian jewelry, unisex like almost all the beauty products of this culture, is as varied as it is spectacular: rings, bracelets, anklets, belts, tiaras, earrings, brooches and spectacular multi-layered necklaces made of copper, silver and gold, with amethyst, agate, carnelian, turquoise, lapis lazuli beads…

Millennia later, their brilliant colors and stylized designs, based on nature, would inspire many of the great creations of modernist jewelers.