In 1975, the British archaeologist Geoffrey Martin, of the Egypt Exploration Society, began the search in the Saqqara necropolis for a very special tomb: that of the henchman of the pharaoh Tutankhamun, the influential and powerful Maya.

But the location of the tomb of this important personage, who held the positions of supervisor of the treasure, head of the works in the necropolis and director of the festival of Amun in Karnak, had already been discovered years before.

The Italian antiquities collector Giovanni Anastasi had explored the courtyard of Maya’s tomb, taking away three beautiful limestone statues of the treasurer and his wife Merit which he sold to the Leiden Museum of Antiquities in 1828.

Years later, in 1843, the German archaeologist Richard Lepsius, leading the Prussian Expedition, excavated the tomb chapel, taking some reliefs to Berlin. But after his departure, the location of the grave fell into oblivion.

Horemheb appears

To try to locate Maya’s elusive grave, Martin relied on a map that Lepsius himself had drawn. In fact, following his instructions, the British archaeologist and his team stumbled upon a large stone column.

But Lepsius’s map was not actually accurate, and the column was not part of Maya’s lost tomb. However, Martin’s surprise when he read the name inscribed in the column was capitalized.

By chance he had come across the tomb of another important personage from the reign of Tutankhamun : none other than General Horemheb,the man who would later become the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty.

“We were convinced that by a miracle we had found the long-lost tomb of one of Egypt’s most famous men, Horemheb, whose actions were well known to all researchers thanks to the many surviving monuments from his reign and other sources.”.

Horemheb began the construction of his tomb in Saqqara before he became pharaoh, and when he took the throne of the Two Lands he ordered the construction of a new tomb in the Valley of the Kings, on the western bank of Thebes, emulating the pharaohs who preceded.

Saqqara’s tomb was never finished, although two of his wives apparently rested there. Martin discovered in one of the burial chambers the bones of Mutnedjmet, Horemheb’s second wife, and the remains of a fetus or newborn.

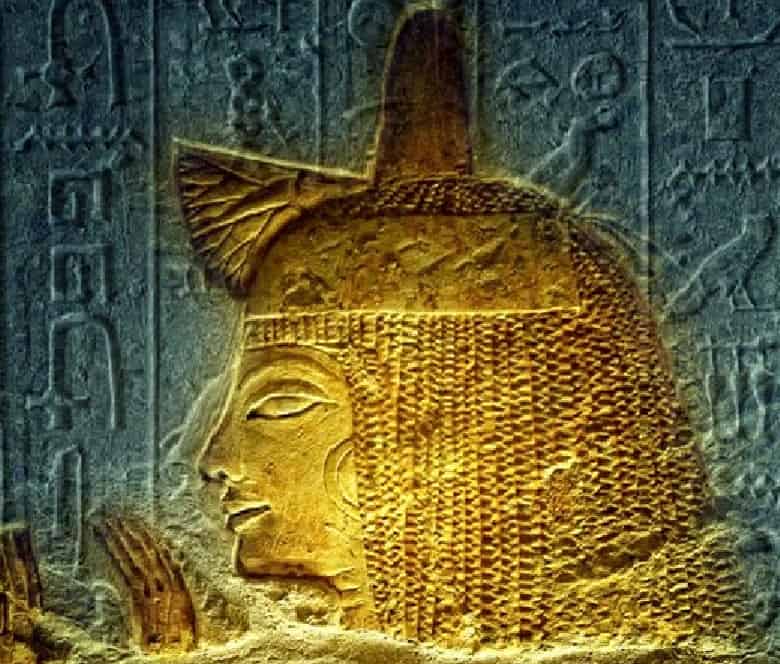

But the real treasure of the tomb of Horemheb in Saqqara are its reliefs, of great beauty and exceptional artistic technique. They represent the then general receiving rewards from the young pharaoh, as well as numerous military scenes.

But the impressive and unexpected find of the tomb of Horemheb did not distract Martin from his true purpose: to find the tomb of Maya.

The archaeologist and his team completed the excavation of the general’s grave and uncovered other nearby graves, that of a sister and a sister-in-law of Ramses II, as well as those of other important figures of the time.

At last, Tomb of Maya

At the beginning of 1986, specifically on February 6, Martin and his team were still digging in Saqqara.

As Martin and a colleague crawled into a newly dug well they stumbled upon a step that appeared to lead to an adjacent grave. In the words of the archaeologist himself:

“A moment or two passed while we walked up the stairs, being careful not to alter anything in our descent.

The ancient thieves must have passed through that place when leaving the underground chambers and there was always the possibility that they had left fall somewhat in their anxiety to escape to the fresh air above.

We did not expect to find anything spectacular and at the time we were busy in the mundane business of getting our generator cable in position located in the desert, about 25 meters above our heads.

A second or two passed; my Dutch colleague and I raised the light bulb and looked down beyond the staircase. We were not at all prepared for what our eyes saw: A room full of carved reliefs, painted a rich golden yellow!”

Martin’s colleague, Dutch archaeologist Jacobus Van Dijk, from the Leiden Museum of Antiquities, studied the text of the reliefs with care and, when he finished, his face showed a clear expression of surprise: “My God, it’s Maya,” he exclaimed.

Martin knew that above them was the superstructure of the tomb. From here, the archaeologists had two possibilities: they could clear the blocked corridor and penetrate the burial chambers (perhaps full of wonders) or they could seal the area and the well that they had discovered by chance and postpone the excavation of the substructure until the following season.

Martin decided on the latter option to general astonishment. How could the archaeologist contain his impatience?

According to Martin, “the reasons are straightforward, even prosaic: archaeologists are not treasure hunters. Underground work would in any case need careful foresight and planning, and logistically it was much more sensible to work from the surface of the desert down than at the bottom reverse”.

Martin and his team had to wait two long years to excavate Maya’s grave. Unfortunately, it had been looted in antiquity, like most tombs in the Nile Country.

But the archaeologist found evidence inside that its contents must have been sumptuous. The floor was littered with fragments of gold leaf that must have covered the coffins, as well as numerous funerary objects left there by the looters in their flight.

Links of a gold chain and fragments of carved ivory that would have been part of the decoration of furniture and boxes were also recovered.

The only thing the archaeologists found intact inside the tomb were twelve ceramic jars. But the lids that sealed them had also been broken by the thieves to check if there was anything valuable inside.

When Martin looked inside he knew why the looters left them there and did not bother to take them: they only contained flour and bread.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic