The Egyptian pyramids have fascinated the Western world for 26 centuries, and have become the symbol of the culture of the Nile Valley. The myths that have been woven around them and their builders continue to live in all those who visit the country.

The elements that made up the pyramidal complex, its function and symbolism, the ritual carried out by the priests, the economic infrastructure it needed to sustain it, the technology applied in its construction or the personnel in charge of it are just some of the aspects that contribute to understanding the complexity of these buildings.

Buildings that go beyond mere architecture to reveal the cultural richness of a nation in the earliest moments of its history.

Since the dawn of the Pharaonic State, and even before, we find in primitive graves some element that shows part of the symbolism that will later be attributed to the pyramidal shape.

The Egyptian, zealous observer and knowledgeable of his environment, with whom he had to live, attributed the emergence and development of life to the small piles of fertile silt that began to emerge when the waters of the annual flood of the Nile descended.

The birth of the world thus starts from a primordial hill from which the sun rose for the first time, which in turn began the creation of all beings and elements.

It is very probable that this idea appears already reflected in some tombs of the proto-dynastic period, whose superstructure (visible part) was covered by a mound of earth, thus symbolizing the rebirth of the deceased to a new life.

The pharaoh incarnates the creator god on earth and is in charge, through daily ritual, of maintaining cosmic order, repeating the initiating act of all existence that the creative divinity once performed.

It can thus be understood that both birth and rebirth were the same thing for the ancient Egyptians.

At the same time, the tomb will be conceived as the residence of the deceased, and will contain everything necessary for their survival.

Both ideas, place of resurrection (hill) and house for eternity, appear perfectly documented from Dynasty I, especially in royal graves. From these very early moments a conception of the afterlife of an underground type is assumed, since the burial chamber is dug into the ground.

The passage to a celestial and solar destiny, which will be exclusive to the kings, will take place in Dynasty III and will mean a true revolution.

Not only does it affect beliefs, but it also represents a whole series of changes in funeral architecture, which will require the adoption of technological innovations.

The revolution

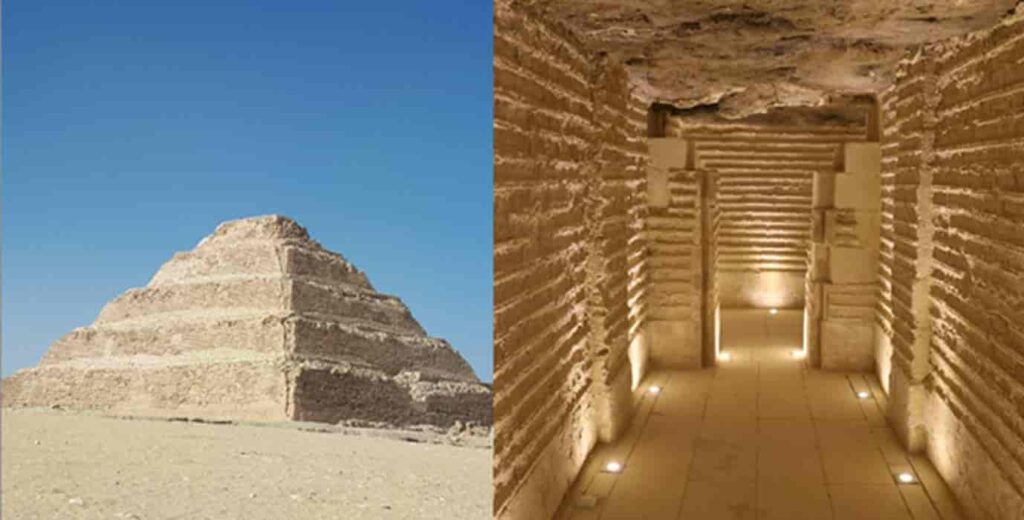

Djoser (c. 2667-2648 BC), pharaoh of Dynasty III, commissioned the construction of his mortuary complex from Imhotep, architect, vizier and high priest of Ra.

He planned an authentic palace for the occasion, possibly a full-scale copy of the one in Memphis . In addition, all the funerary buildings destined to ensure the rebirth of the king were included in the enclosure.

In keeping with tradition, Imhotep creates a mastaba, which he will enlarge twice. However, later, and without knowing the circumstances that led him to make that decision, he reconverts the initial mastaba into a pyramid of four steps, to which he will add two more, for a total of six.

This change of idea is fundamental, since it was not only a technical innovation (the construction involved the acquisition of previously unknown architectural knowledge), but it also manifests a new vision of the conception of the afterlife.

As the Pyramid Texts will later point out, the structure is a gigantic stairway so that the king can ascend through it and reach heaven.

Thus, and for the first time, in the Djoser complex we find two possibilities from beyond: the primitive underground (the chamber is still excavated in the ground) and the celestial, whose instrument of ascension is constituted by the pyramid.

This, in turn, represents the primordial hill, and therefore the place of transformation of the monarch to his new state of rebirth.

The architect of all this was Imhotep. No doubt, as the high priest of Ra, he used his influence over the king to help change his mind. Since then, the solar god will acquire primacy in the pantheon, as also, evidently, his clergy.

The relationship of the royalty of the Old Kingdom with Ra will from this moment be very close, and will be felt in all aspects of Egyptian culture.

The pyramid reflects the symbol of that union of the pharaohs with the solar divinity. Djoser’s successors not only use it as a tomb, but a multitude of small pyramids will be built throughout Egypt, probably as a reminder to its people of the monarch’s extensive power, but also of his benefactor nature.

Imhotep had a profound impact on the later Egyptian mentality, to the point of considering him their first sage and even being deified.

To Djoser and Imhotep we also owe the habitual use of stone in architecture. Although it is known that the last monarchs of Dynasty II began to use it in the construction of their tombs, the development of the working technique is seen in their funeral complex in Saqqara.

It is an initial phase, and the artisans do not yet know its constructive possibilities. For this reason, the stone is carved into small blocks slightly larger than mud bricks.

Gradually, and through practice, they will become familiar with its characteristics and potential, while perfecting the extraction, carving, transport and placement techniques.

A good example of this are the multi-ton blocks that are known from Dynasty IV. The first pharaoh of this, Sneferu, ordered to build three huge pyramids in succession.

With it one advances towards the geometrically perfect pyramid, but also towards the characteristic funerary complexes of the Old Kingdom.

In this sense, two aspects stand out. In the first place, the stepped structure, which will remain only in the nucleus (Meidum pyramid), is abandoned to build the smooth-faced pyramid for the first time.

Secondly, with this king, the pyramidal complex appears in its basic structure, which incorporates two temples and a causeway that connects them, as well as subsidiary pyramids and an enclosure.

Undoubtedly, the fullness of forms and proportions is reached with his son khufu, who takes the necropolis a little further north, to the Giza plateau, creating the largest pyramid we know, which is next in size, that of his son Khafre.

The dimensions will decrease greatly from now on for reasons not yet convincingly explained, but the smooth-sided pyramid will maintain similar proportions, although the construction technique will vary over time.

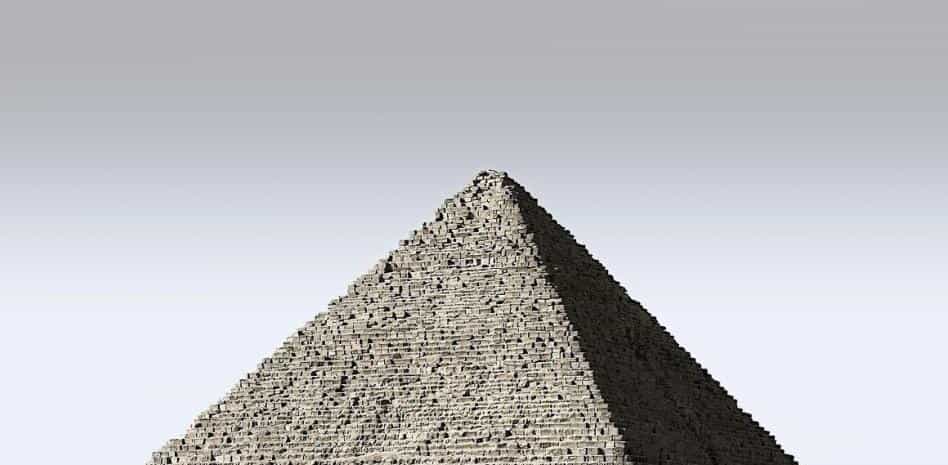

At this time of Dynasty IV, the structure is formed from rows of limestone blocks, to which a white limestone coating from the Tura quarry is placed. Sometimes (in Khafre and Menkaure), the lower courses are red granite.

The pyramids of dynasties V (Abusir necropolis) and VI (mainly in Saqqara) are smaller in size and their core of poorer quality, made with clay, mortar and small irregular stones.

However, as they appeared covered with white limestone, the appearance they offered was still spectacular. Such blocks were reused throughout history, so today these buildings offer us a ruinous image, since they have suffered great erosion and collapse.

From the V dynasty, two new elements are introduced that are important to highlight. The first is the construction in the royal necropolis of a solar temple (basically composed of a large open-air courtyard, an obelisk on a platform and a solar boat) linked to the pyramidal complex.

It is not known if the antecedent is found in the Great Sphinx of Giza and its sanctuary, also of a marked solar character.

The second is the appearance of a set of funerary texts recorded in the antechamber and burial chamber, the Pyramid Texts, whose purpose was to help the king reach the afterlife.

They appear in the pyramid of Unas, the last pharaoh of the V dynasty, but they will continue to be used in the VI.

After the Old Kingdom

The pyramidal complex as a form of royal burial was not unique to the Old Kingdom. The monarchs of the XII and some of the XIII dynasty used it for their dwelling of eternity, although the materials used at that time for the nucleus (adobe, stone rubble …) have not left remains as spectacular as those of the time previous.

In fact, they suffered looting and their limestone coatings were also reused in other constructions. Although some of these complexes are in the necropolises near the ancient capital, Memphis, most were built in the vicinity of el-Fayum, where the administrative capital of Egypt was located at that time.

The last documented royal pyramids in Egypt were built by monarchs of the 17th dynasty at the Dra’ Abu el-Naga’ Necropolis on the western shore of the Theban region.

These are very small buildings that must have been around 10 m on each side, of which there are no remains.

From the 18th dynasty the cemetery was moved a little further south, using the mountain for the construction of hypogea (underground tombs).

The elements of the pyramidal complex continue, but more geographically extended. Although there are no superstructures in the Valley of the Kings, it seems that the landscape of the area itself influenced its choice as the location for the new necropolis: one of the mountain peaks, called el-Qurn, under which the valley is located, has pyramid shape.

A natural accident of the terrain continued to offer symbolically and physically the monarch’s access mechanism to his celestial and solar beyond.

At the end of the 18th dynasty the pyramidal form appears again, although this time we find it in non-royal tombs. Thus ends the exclusivity of its use by the monarch and his closest family.

Examples are known from various places in Egypt and Nubia, such as some graves of the artists who built and decorated the Valley of the Kings.

Above the chapel of funerary worship stood a small hollow adobe pyramid; This was crowned with a limestone pyramid, engraved with scenes of the deceased seated before an offering table or venerating the solar god.

From this same period we also know those of high dignitaries of Memphis, who were buried in Saqqara in tombs whose superstructure reproduced a temple topped by a small pyramid, or it sat directly on the ground, next to the west wall of the chapel.

It would be necessary to emphasize that they do not only appropriate the form, but also what it implies: a beyond of solar and celestial character that in previous stages was reserved exclusively for the pharaoh.