The Beautiful Festival of the Valley was one of the most popular and significant festivals in ancient Egypt. It was celebrated annually in Thebes from the time it was initiated by Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom until Roman times.

It was a state festival, with the pharaoh and his family participating, and it served as a funeral rite dedicated to the deceased.

The festival took place at the New Moon of Month Two, which corresponded to the summer season, known as shemu, and was the 10th month in a calendar of 12.

The king himself oversaw the ritual, serving as an intermediary between the living and the dead.

The Beautiful Festival of the Valley evolved over the years. Initially, the procession was limited to the route between the Karnak temple and Deir el-Bahari, but over time, it expanded to include visits to other necropolises and funerary temples, such as the Ramesseum.

The sacred boats of Amun-Ra, his wife Mut, and their son Khonsu departed from the Karnak temple to visit the funerary temples of the deceased kings on the west bank of the Nile and their shrines in the Theban Necropolis.

The statue of Amun-Ra was carried on the shoulders in a ceremonial procession from the Karnak sanctuary to the bank of the Nile, where it was embarked upon to cross to the western bank. From there, it was again carried on the shoulders, making stops at various chapels along the way where the boat rested.

Various rituals were performed at these stops before reaching the sacred valley of Deir el-Bahari and the temple of Hathor at the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.

In this manner, the temple of Karnak and the funerary temple of Hatshepsut were physically and symbolically linked as an axis that connected the world of the living with the world of the dead.

Amun-Ra, in this manner, traversed the realm of the afterlife, and those in attendance could draw upon his revitalizing energy.

The king and his family were accompanied by ancient Egyptians who had their ancestors interred on the opposite shore (the shore of the dead) to pay homage to them and make offerings.

Funerary rites and feasts occurred in this place, and ostracas were left behind with prayers and requests to the god, imploring him to heed their entreaties.

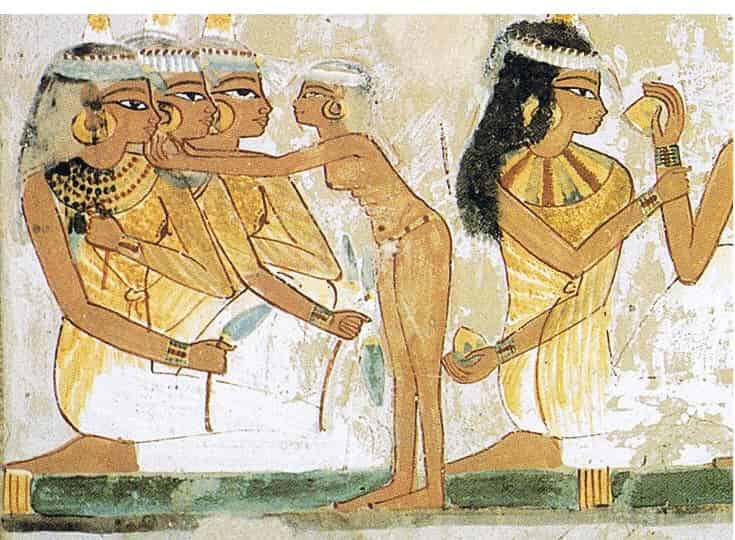

Various acrobats and musicians entertained the throngs of people, while women played the sistrum, a type of rattle or instrument producing a melodious sound, gentle like the breeze rustling through papyrus reeds, believed to soothe the gods.

As twilight descended, the queen and the priests ceremonially positioned four torches at the four corners of the boat where the deity’s statue rested.

In this manner, the four cardinal points were illuminated, dispelling the darkness and the malevolent forces that imperiled the divinity’s stability.

Afterwards, they presented an offering of four large vessels of milk, ensuring peace and sustenance for the god, and the torches were positioned atop these vessels.

Through this ceremony, it was understood that the divine presence extended not only within the confines of the temple but also throughout the necropolis, safeguarding the departed and their kin. At daybreak, the torches were extinguished, marking the conclusion of this ritual.

The festival reached its culmination as the procession retraced its steps to the point of origin on the eastern bank of the Nile, the realm of the living. Amun had succeeded in rejuvenating his vigor, triumphing over death once more, and fortifying the bond between the living and the deceased.

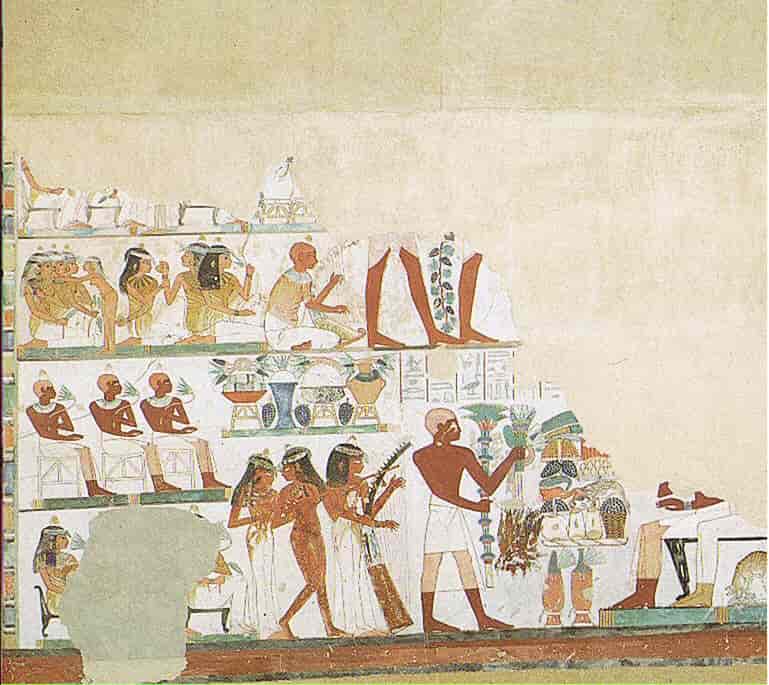

Numerous depictions characteristic of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley adorn sites such as the Tomb of Nakht. Serving as a jubilant and widely attended occasion, these scenes often feature officials, musicians, singers, and dancers.

During funerary feasts, individuals are portrayed inhaling the aroma of the Egyptian blue lotus. These plants, from which substances possessing psychoactive properties are derived, may have been utilized in rituals associated with these festivals to facilitate communication between the living and the dead.