A friend and collaborator of the Macedonian monarch Alexander the Great, Ptolemy took control of ancient Egypt after the conqueror’s death. Proclaimed pharaoh, he established the first Greek dynasty in Egypt.

Ptolemy’s fate was one of the most extraordinary in antiquity. Raised to live the typical life of a Macedonian aristocrat, he embarked on Alexander the Great’s magnificent conquests of Mesopotamia, Persia, and India before the age of 30. Eventually, he was crowned King of Egypt and celebrated as Soter, meaning “savior.”

Other generals of the Macedonian conqueror also managed to claim a portion of his legacy to construct vast kingdoms, but Ptolemy amassed the most power and was the only one to avoid dramatic reversals of fortune, living to an advanced age and dying a natural death.

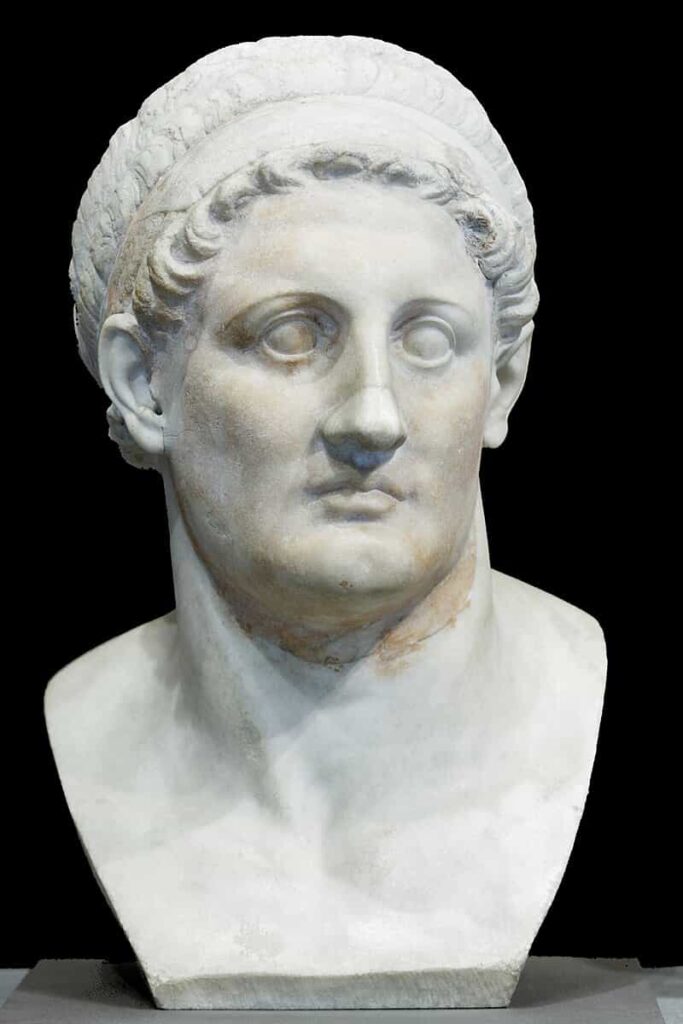

Ptolemy, a Macedonian nobleman

Ptolemy was the son of a Macedonian nobleman named Lagus (thus giving rise to the Lagid dynasty, which he founded) and Arsinoe of Macedon, a woman perhaps related to the Macedonian royal family.

The youth of the future pharaoh was spent at the Macedonian court, and he quickly became one of the close friends of Prince Alexander. His father, King Philip II of Macedonia, viewed his popularity with suspicion and decided to exile him, but Alexander brought him back to be a part of his army from the outset of his campaigns against Persia. Since then, Ptolemy never parted ways with the young conqueror, and his role in the Indian campaign earned him the title of commander.

Ptolemy was one of the seven bodyguards in Alexander’s personal guard, a position that would be crucial upon the death of the Macedonian ruler in 323 BC. In Babylonia, where Alexander’s generals divided the empire, Ptolemy seized one of the most valuable territories: Egypt. Moreover, he made a strategic move by taking possession of Alexander’s body and choosing to bury him in Egypt.

Ptolemy I: The Beloved Satrap

Initially, like the other successor generals of Alexander, Ptolemy served as the representative of his legitimate heirs: his elder half-brother, Philip III Arrhidaeus (who had diminished mental faculties), and his son Alexander IV (born to a princess of Sogdiana, Roxana).

All the monuments that Ptolemy constructed or restored in Egypt were dedicated to one of the two sovereigns. Even after the assassination of Alexander IV in 311 BC, Ptolemy continued to present himself as the satrap or governor of Egypt for a few more years.

However, this did not stop him from being celebrated as the de facto ruler of the country, as evidenced by an extraordinary document from that period, the “Satrap’s Stele.” This lengthy text lavishes praise upon Ptolemy:

“There was an exceptional viceroy [satrap] in Egypt named Ptolemy. A man of youthful energy, strong in arm, wise of mind, and powerful among men, possessing fierce courage […] who fearlessly confronted his enemies in battle.” It also recalls the spoils he acquired from his campaigns: “He brought back the images of the deities discovered in Asia, as well as all the sacred tools and books that belonged to the temples of Egypt.”

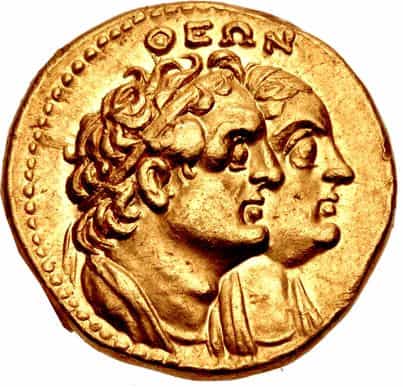

Ptolemy I Soter: A Pharaoh of Greek Origin

Finally, in 305 BC, Ptolemy declared himself the king of Egypt. A year earlier, his rival Antigonus, another one of Alexander’s generals, had also done the same, proclaiming himself king in Syria after incorporating the region into his domain.

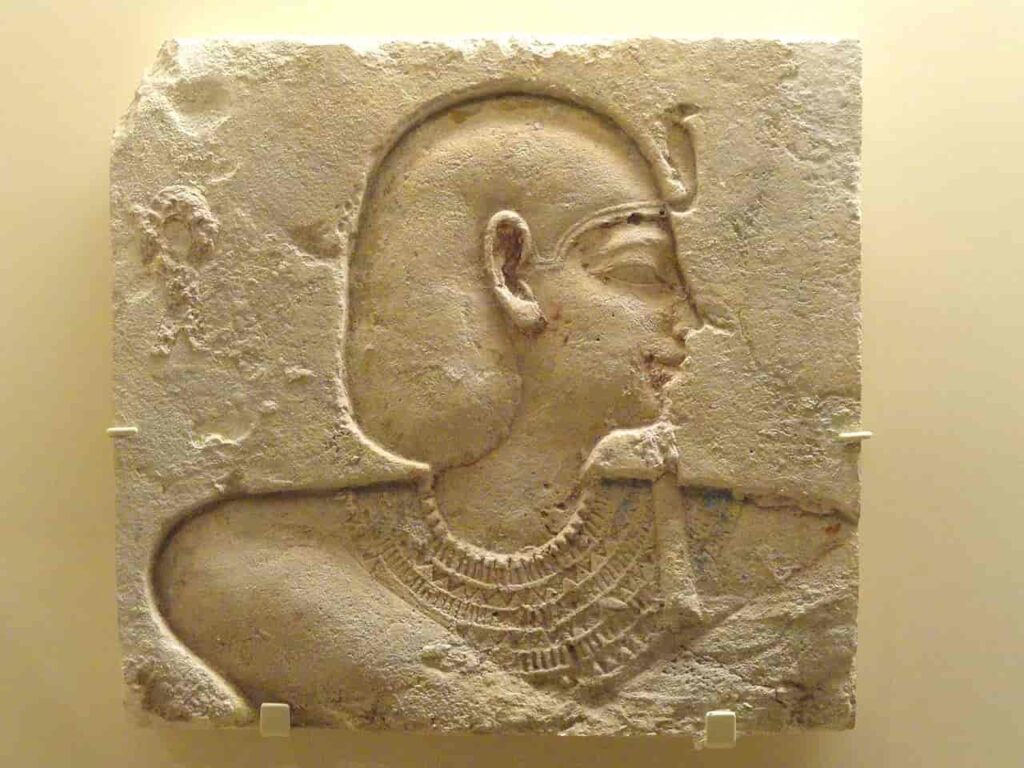

Undoubtedly, Ptolemy aimed to leverage the prestige associated with the title of pharaoh that he now held. Despite his Greek heritage, Ptolemy went through the coronation process following the Pharaonic tradition. He portrayed himself on a papyrus boat, capturing the birds dwelling in the Delta marshes—a metaphor for his triumph over chaos and a symbol of his determination to eradicate all malevolence that threatened Egypt.

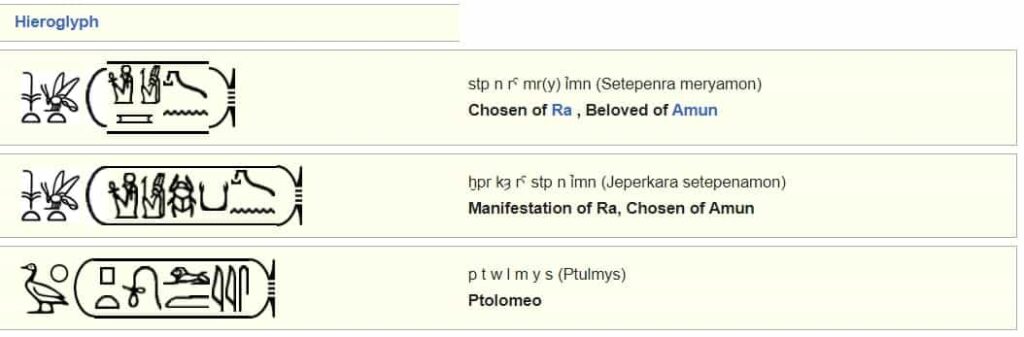

Furthermore, he commissioned the creation of his own pharaonic decrees. For his throne name, he chose Meriamun Setepenre and Kheperkare Setepenamun, which translate to “Beloved of Amun, the chosen one of Ra” and “The ka of Ra is born, the chosen one of Amun.”

These titles had been previously used by pharaohs like Senusret I and Ramses II, whom Ptolemy may have sought to emulate. While he reserved the highest positions in the administration for Greeks, he did not completely exclude Egyptians, who held roles such as scribes.

Similarly, the clergy retained their privileges. Evidence of this can be seen in the aforementioned Satrap’s Stele, which includes a series of land grants to the priests of the temple of Wadjet (the cobra goddess and protector of royalty) in the city of Buto, located in the Delta region.

Source: Núria Castellano, National Geographic