One of the most captivating tombs in the Valley of the Kings is that of Horemheb. This general, whose name means “Horus is celebrating” in Egyptian, served as the final pharaoh of the 18th dynasty and governed ancient Egypt from 1323 to 1295 BC, following a tumultuous period of political disorder, though his reign itself was notably tranquil.

Once the nation was pacified, Horemheb initiated several significant construction projects, including the grand hypostyle hall of the Karnak temple and his own tomb in the Valley of the Kings (known as KV57), which may have been left unfinished as the pharaoh passed away before its completion.

However, this wasn’t the sole tomb Horemheb prepared for his eternal resting place: prior to assuming the throne, while still serving as commander-in-chief of Akhenaten’s armies, Horemheb commissioned a magnificent tomb in the necropolis of Saqqara, near Memphis, which he never occupied.

The Discovery

Horemheb’s tomb was unearthed on February 22, 1908. Archaeologists unveiled a series of steps leading down to the entrance door. Once they cleared away the intentionally placed rubble blocking the passage, a lengthy corridor emerged, delving underground for approximately 128 meters. This corridor led to two monumental chambers, each adorned with colossal pillars carved directly into the rock.

Spanning a total area of 473 square meters, the tomb garnered attention for its magnificent mural decorations. However, during their initial exploration, archaeologists encountered scattered remnants of mummies, figurines, and other artifacts—a clear indication that looters had plundered the site in ancient times. Thus, it became evident that this was not an intact royal tomb.

Corridors, Wells, and Chambers

The Tomb of Horemheb (KV57) cuts through the rock via a series of stairs and ramps, punctuated by several chambers until reaching the funerary chamber housing the pharaoh’s sarcophagus.

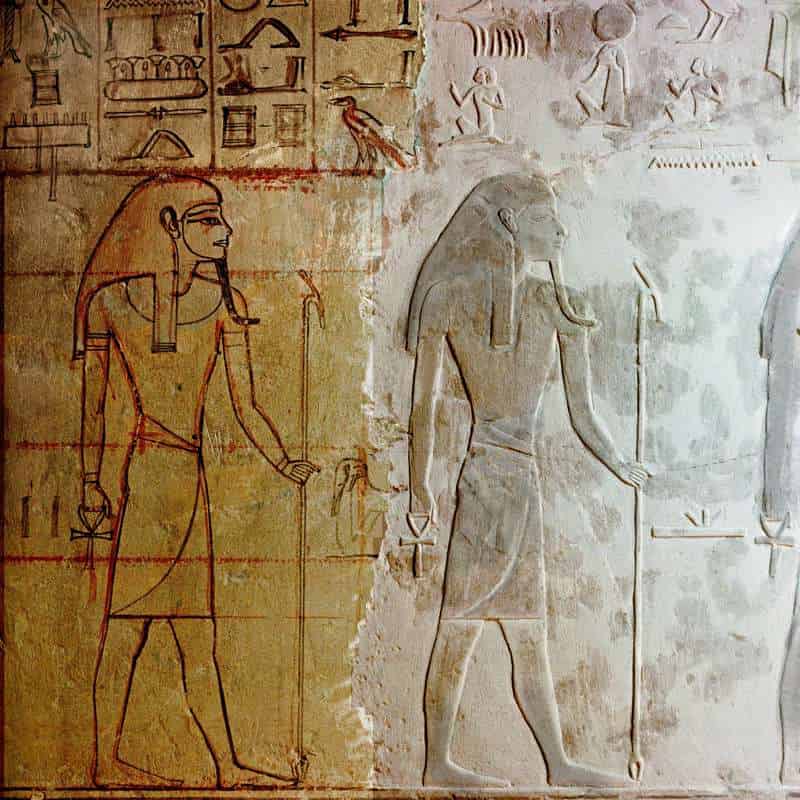

The initial corridors of the tomb remained undecorated, yet they reveal the limestone bed and the various layers of flint meticulously drilled by the pharaoh’s laborers. Decorations adorn the well chamber, the antechamber, and the burial chamber.

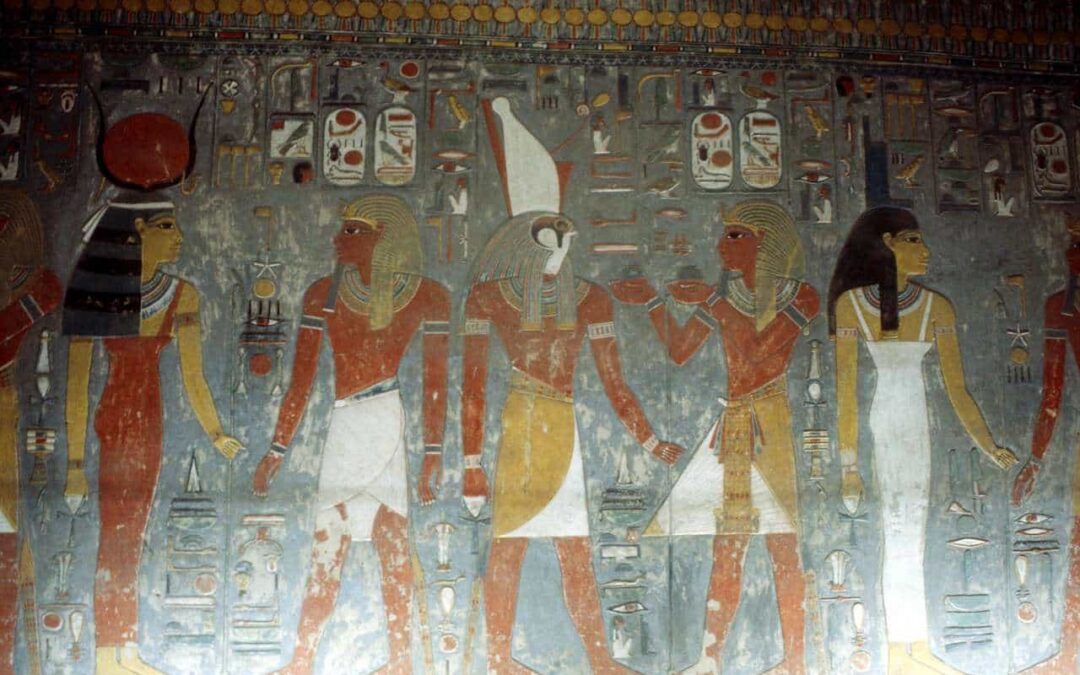

In the well chamber, Horemheb is depicted before several deities—a notable departure as it marks the first instance of a king offering homage to the gods within a tomb.

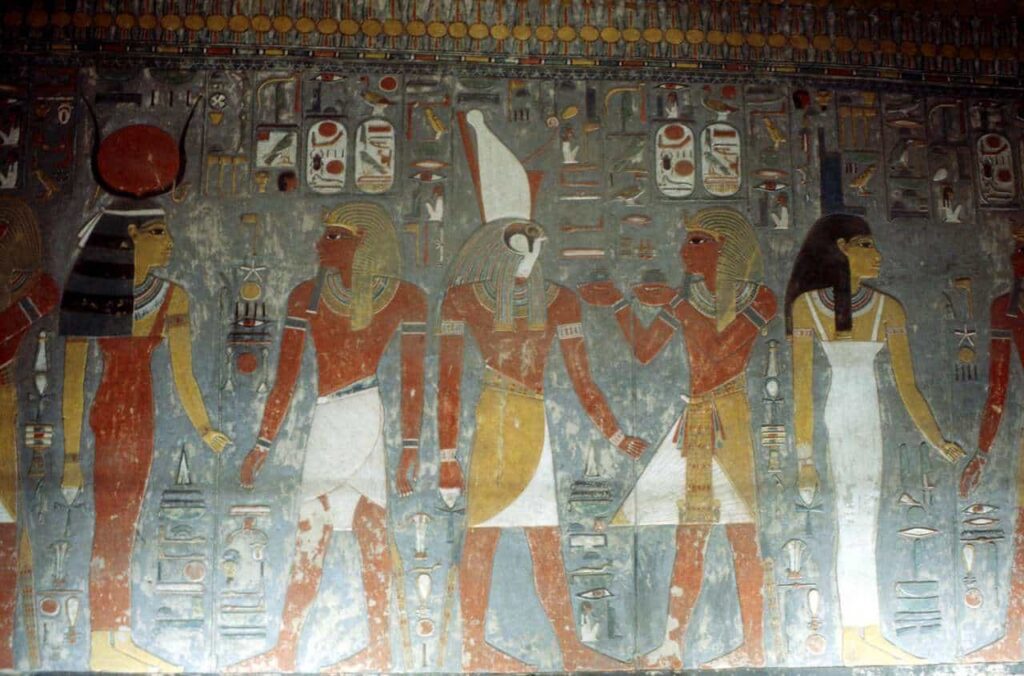

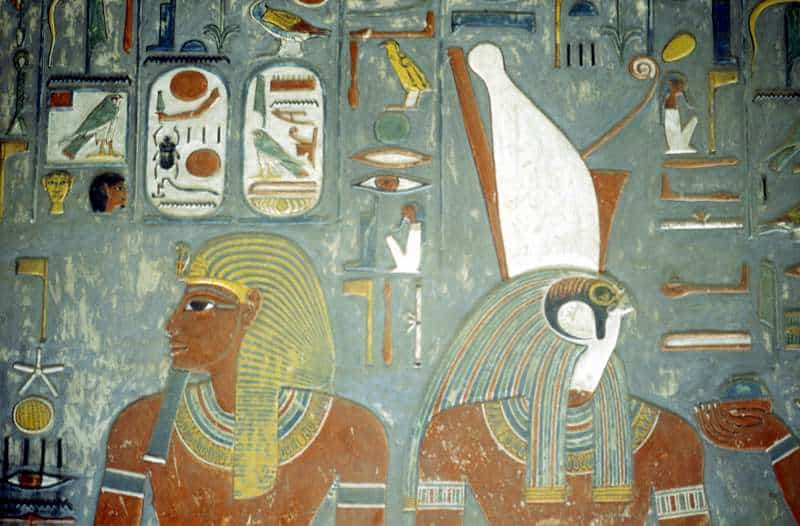

This segment of the decoration captivates with its nearly imperceptible relief—a technique introduced for the first time in the Valley of the Kings, supplanting traditional mural painting. The figures are rendered in vibrant polychrome against a subdued grayish-blue backdrop.

The arrangement of scenes creates a harmonious tableau, highlighting intricate details in the hieroglyphs and the attire of the depicted figures.

Upon descending a corridor and a staircase, one arrives at an antechamber adorned with scenes akin to those found in the well chamber.

This chamber leads into the funerary chamber itself, comprised of the Room of the Six Pillars, the sarcophagus chamber, and several smaller rooms.

The wall decorations abruptly cease, revealing red sketches drawn by artisans and corrected in black ink by their master, indicating areas where sculptors had yet to commence work.

Despite the interruption, the composition exhibits remarkable quality, featuring exceptionally detailed renderings. The paintings depict passages and scenes from the Book of Doors, a New Kingdom funerary text narrating the nocturnal journey of the Sun god through the underworld and the perils he encounters.

During this journey, the solar deity Ra confronts twelve gates dividing the night hours, guarded by dreadful beings and monstrous serpents breathing fire. The adornment of tomb KV57 stands as the earliest documented representation of this sacred text.

The Missing Mummy

Within the tomb chamber, a magnificent rectangular sarcophagus crafted from pink granite was uncovered, displaying remnants of the distinctive style prevalent in the court of Akhenaten and Nefertiti in Amarna. The lid, initially found on the ground upon the tomb’s discovery, was shattered.

Resting atop a limestone base, the sarcophagus was symbolically supported by six wooden figures (of which five were found in situ), positioned within holes in the ground on each side.

Scattered across the floor of the burial chamber lay other fragmented images, alongside remnants of desiccated flowers from funeral garlands.

Furthermore, within the side chambers, remnants of the funerary trousseau left behind by the thieves were recovered. These included various wooden figures of gods coated in resin, miniature boat models, faience beads, stone vessels containing preserved provisions, an alabaster chest for the canopic jars, human bones, and tools.

Contained within the sarcophagus were a skull and assorted bones, yet notably absent was the mummy of the pharaoh. It is highly likely that it was pilfered during one of the ancient lootings, as it has not been located in any of the caches housing the royal mummies of the New Kingdom, where over forty have been unearthed. The absence of his mummy remains one of the enduring mysteries among the pharaohs who once ruled over ancient Egypt.

Source: Irene Cordón i Solà-Sagalés. National Geographic.