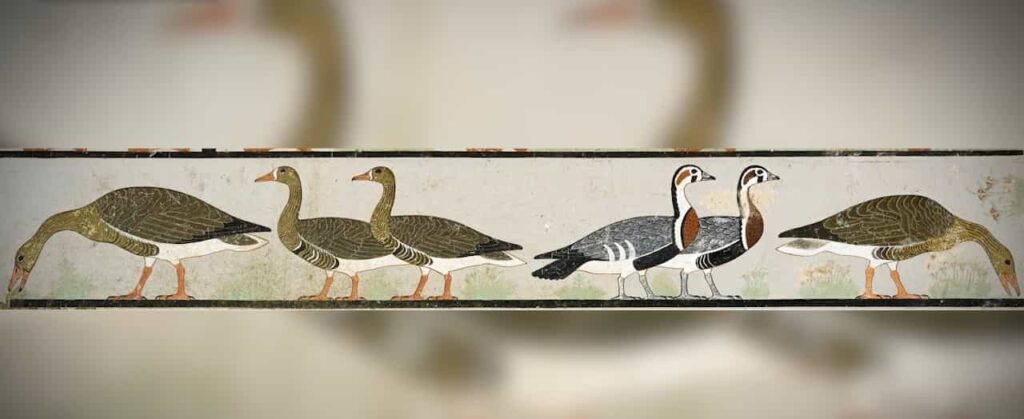

The Meidum Geese is one of the most beautiful examples of ancient Egyptian painting. Its delicacy and naturalism decorated the tomb walls of Nefermaat, dating from about 4,500 years ago.

It was discovered by Auguste Mariette and transferred to the Cairo Museum, where today, it continues to amaze the public with its timeless modernity.

Meidum is a small town south of Cairo, known for its famous pyramid. But its name is known to us because of another important and very different find: the so-called “Meidum Geese”, which represents one of the oldest parietal paintings ever found preserved from ancient Egypt.

As the son of Pharaoh Sneferu, a vizier and person of great resources, Nefermaat must have had the most outstanding artists of the time at his disposal.

It also reflected some artists who did not hesitate to resort to the experimental and most innovative to decorate the tomb of the prince.

Nefermaat’s wife, Itet, also enjoyed the work of creators of great mastery, capable of displaying remarkable creativity.

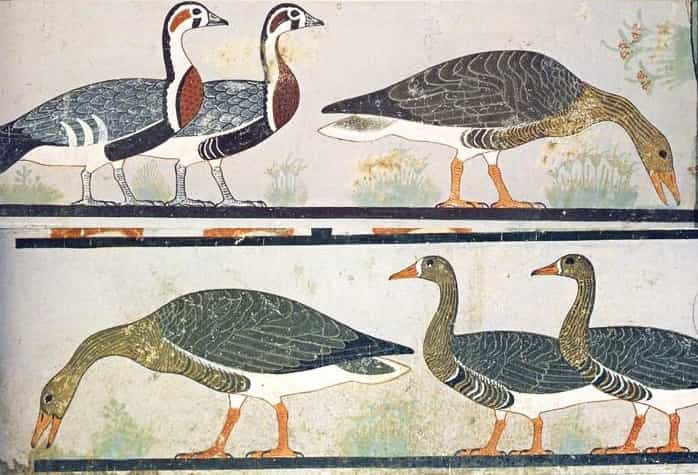

Paintings such as the Meidum Geese amply corroborate this. The geese in the Itet chapel were made following the most conventional Egyptian pictorial technique.

Stucco painting was a very common technique in ancient Egypt since it facilitated decoration with the economy of means and time, even on the most difficult surfaces such as ground stone or adobe.

The walls were covered with a layer of plaster, pure or mixed with straw, and then rubbed to obtain a smooth paint surface. Colors were easily obtained from nature: red and yellow ochre, chalk white, carbon black, azurite, malachite, and faience, while turquoise glass paste was used to enamel statuettes, vases, and amulets. These materials could be used pure or mixed to create smooth effects.

The colored tablets were pulverized on a palette diluted with water and a binder, such as albumen or vegetable gum, and then applied as tempera with broad palm fiber brushes.

Unfortunately, the fragility of the support made the works vulnerable to aging; the action of man and the Geese of Meidum are only a few examples that have been preserved.

Although the depiction of animal life was common in funerary iconography, the execution rarely reached the artistic level of these panels.

The scene is dominated by six geese in two groups of three against the background of a garden containing tufts of grass and flowers.

There are no gradations of color in it, and no attempt is made to create shadows; the line is elegant, and the drawing is devoted to the naturalistic description of bird species.

An abstraction, then, but in this exquisite work, you can appreciate the love for details, the color sensitivity, and an evident approach to reality and nature.

The risk of limiting the painting to obey the rules of pictorial symmetry that sometimes hardened the hand of Egyptian artists is solved here by including different details, such as the plumage and the end of the tail.

The intention to create a rarefied atmosphere in which the harmony of contrasting colors would be in perfect harmony with the location of the geese in the landscape is also evident.

Since the first dynasties, the banks of The River Nile have been inhabited by this beautiful duck. The geese not only served as food for the ancient Egyptians but were also offered to the gods as offerings.