After passing away, and before being buried in his tomb, the deceased’s mummy had to undergo a complex ceremony to help him regain his senses through magic and, thus, be able to enjoy a full life in the afterlife.

Egypt during the New Kingdom. It is not just any day: Pharaoh is dead. In order for the deceased king to be able to meet the gods and enjoy eternal life, the most scrupulous observance of funeral rituals will be necessary.

After the mandatory seventy days that the mummification process lasts, the royal mummy is placed in a boat at the head of a small fleet that will take it up the Nile to its last resting place: the Valley of the Kings, west of Thebes, the capital of the country.

The deceased king’s successor leads the funeral caravan, while the inhabitants of the Nile country, his subjects, mill about on the banks to bid their pharaoh the last goodbye, breaking the silence with their cries and laments.

The new pharaoh is expected to play an active role in the funeral of his predecessor since only by strictly following the ritual can he ensure his legitimacy as heir to the throne of the Two Lands.

The journey to the grave

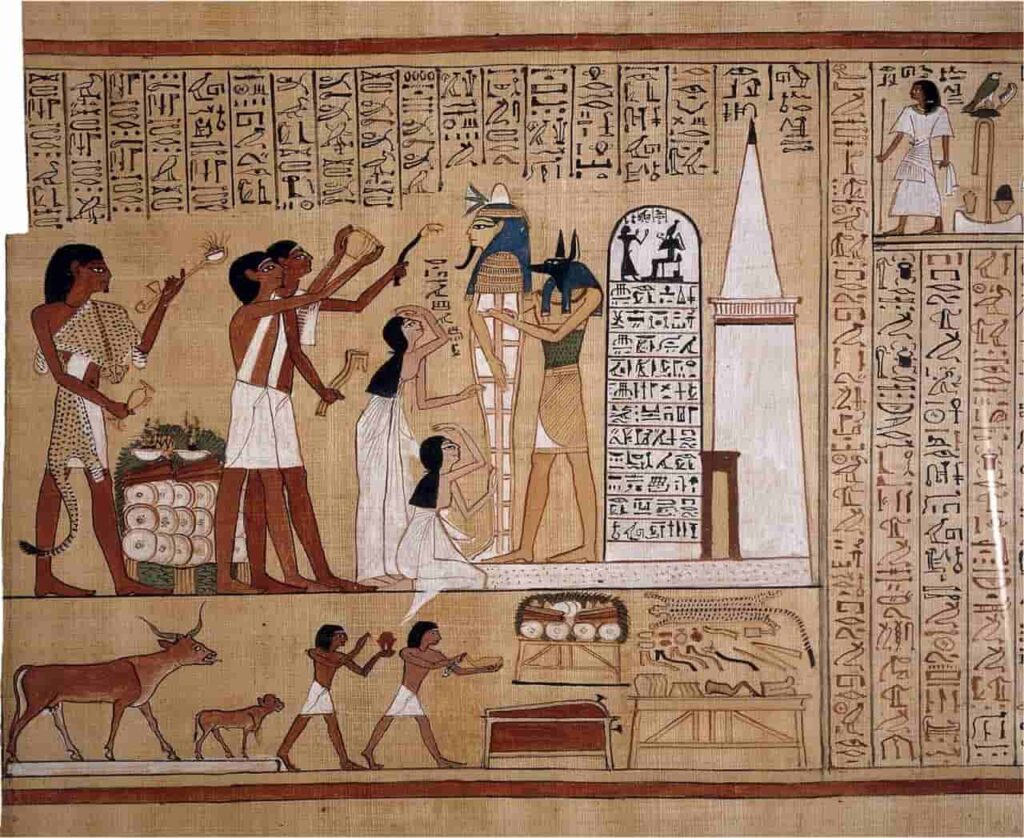

After disembarking, the coffin with the royal mummy is placed on a platform pulled by two oxen to be transferred to the tomb.

But the late pharaoh will not go alone. His last trip will be accompanied by a large procession composed of shaven-headed priests who fill the environment with their songs and the aroma of incense.

Professional mourners who scream, cry, moan, and tear their garments while desperately stroking their hair; servants who transport the belongings that will make up the king’s luxurious funerary equipment …

The funeral procession is closed by two women dressed as the goddesses Isis and Nephthys, the two mourning sisters of Osiris, who with spread wings protect the deceased.

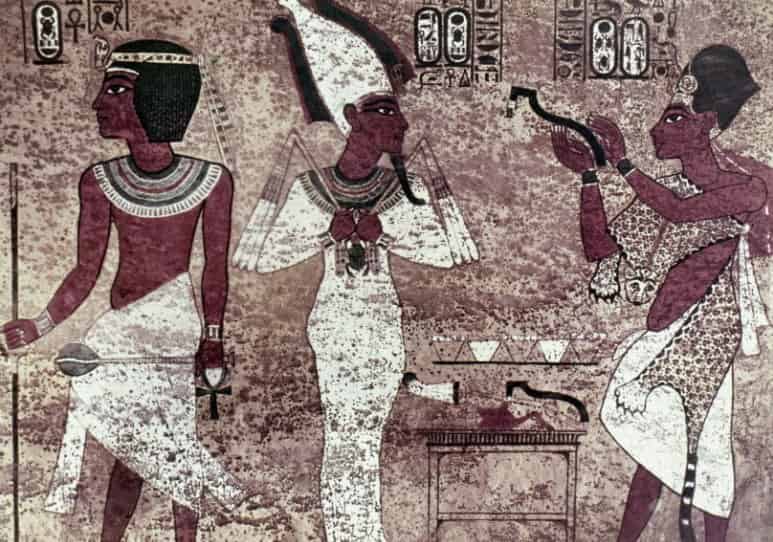

When the procession arrives at the doors of the royal tomb, a sem (pure) priest, who wears a mask with the effigy of the god Anubis, asks permission to carry out the burial.

At that moment a group of Muu-dancers appear, performing a ritual dance in front of the coffin to confirm that the funeral can continue.

Subsequently, a reading priest reads some passages from a funerary text.

Once these rituals are finished, the coffin, with the mummy inside(some authors maintain that the ceremony was done before the mummy, which had been taken from the coffin; others believe that it was performed before a statue and that it took place inside the burial chamber).

It is put up in front of the door of the burial to carry out the most important rite of all, the one that will allow the deceased to regain all his senses to be able to live fully in the afterlife: it is the so-called ceremony of “the opening of the mouth and the eyes”.

Resurrection Ritual

The ceremony of the opening of the mouth (as it is known in its abbreviated form), a ritual of which we have evidence from very remote times, was not exclusive to royalty, but was carried out on the mummy of any deceased with the purpose of assuring him the full recovery of all his senses (speech, sight and hearing) for his afterlife.

Thus, this ceremony was the confirmation that death was not the end, but the beginning of a new life that would last forever.

The steps (75, according to some texts) that the priests in charge of the ritual followed were very complex and loaded with mysticism.

The recovery of each sense corresponded to a different god who was represented by a priest dressed in a mask of divinity.

For example, the god Ptah, creator god of Memphis, was in charge of symbolically “opening” the mouth of the deceased so that he could regain speech, and the funerary god Sokar was in charge of the recovery of sight.

To carry out the magical ritual, the priests normally used elements made with meteoric iron since it was thought that this material from the sky was sent by the gods.

Among these instruments were several adzes, a fishtail-shaped staff called a peseshkef, and a knife decorated with the head of a serpent called an uerhekau.

With them, the priests touched the limbs and organs that were to be brought back to life, mainly eyes, nose, ears and mouth, so that the deceased could eat, drink, speak, hear, smell and see in the afterlife.

In the Book of the Dead (a compendium of funerary formulas intended to facilitate the journey to the underworld) there is a passage in which the deceased refers to the ritual:

“My mouth is opened by Ptah, / the bonds of my mouth are released by the god of my city. / Thoth has come fully equipped with spells, / unties Seth’s bonds from my mouth. / Atum has given me my hands, / they stand as guardians. / My mouth is given to me, / my mouth is opened by Ptah / with that metal chisel / with which he opened the mouth of the gods.”.

Food and drink for the deceased

Once the deceased had regained his senses, the sacrifice of one of the oxen that had participated in the funeral procession was carried out.

Aided by the thigh of the animal (which was sometimes not real, but a tool that had this shape), the sem priest “opened” the mummy’s eyes and mouth four times.

Afterwards, the dead man’s mouth was reopened with an adze. Since the deceased was now able to eat and drink, he was presented with a series of food offerings and a cup of water.

Meanwhile, the servants were depositing the grave goods inside the tomb.

Finally, and after “cleaning” the bandages that covered the eyes and mouth, a copy of a funerary text was placed (usually the Book of the Dead ) inside the coffin and it was taken to the burial chamber.

If the deceased was the pharaoh, his coffin would be deposited inside a stone sarcophagus. When they left, the group in charge of all these tasks erased their tracks.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic