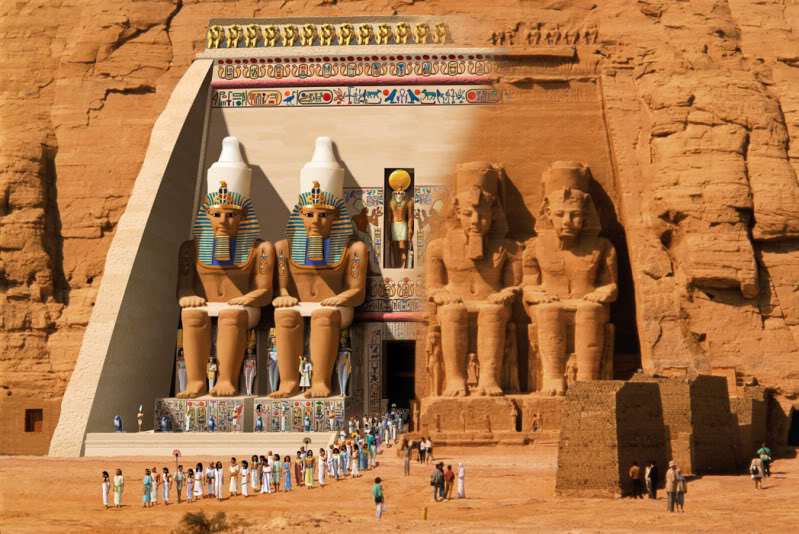

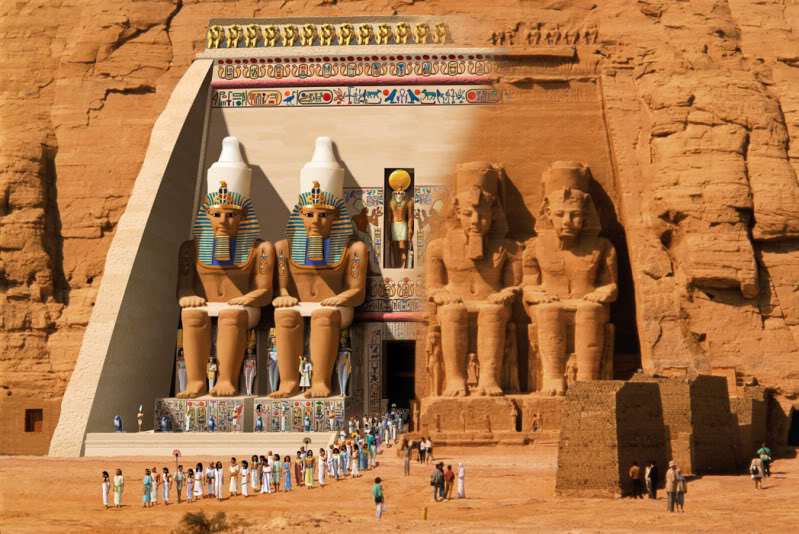

When we see Greek or Roman sculptures today, we often imagine them sculpted in white marble. But the truth is that both the temples and statues of ancient cultures, including those of ancient Egypt, were once covered in colors that have mostly disappeared over time.

The painters and sculptors of ancient Egypt were not considered artists, but rather craftsmen. They were paid like any other worker, with goods that allowed them to survive. Some of them achieved recognition, but these were a minority, and none of the paintings or sculptures are typically signed by the artist.

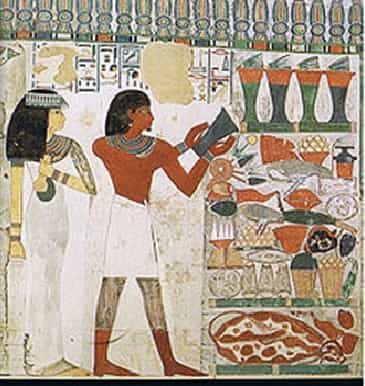

In the case of painting, it was closely linked to daily life, which was often depicted in houses, temples, and tombs. In these tombs, images related to death and resurrection in the afterlife also appeared, as the function of these paintings, along with statues and mummification, was to preserve the image of the deceased and their possessions for the afterlife.

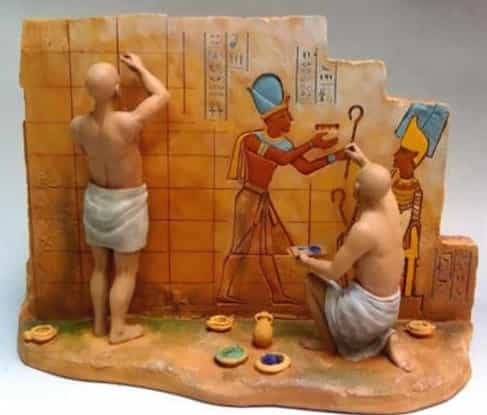

A foreman directed the entire process of making the paint, which began with the preparation of the wall. The wall was stuccoed to remove any imperfections and then a grid was drawn.

This grid was made by soaking a rope in red paint and stamping it against the wall. The draftsman, or “contour scribe,” then used this grid to make his drawing with millimeter proportions.

For example, the human body was governed by a scale in which a standing man would measure about 18 squares of the grid. 2 squares corresponded to the face, 5 to the torso, 5 to the upper part of the legs, and 6 that went from the knees to the feet.

The draftsman designed these scenes first on papyrus, ostraca, and/or wood, and then made the outlines in yellow, red or black on the chosen wall. When it was clear that the wall was to be painted, the background was colored and the outline of the figures was marked to be colored later.

Each artisan was in charge of a color and applied it all at once. It could also be done in relief, chiseling the wall with a mallet to reduce the surface and then giving color to the interior.

The artisans used a specific set of tools for their work. The relief was made with a chisel and a mallet, and stone palettes were used to mix pigments with water. There were two types of brushes: one used by the draftsman for outlines, which was simply a very fine reed with a crushed end, and one for applying paint, made of reeds with chewed ends.

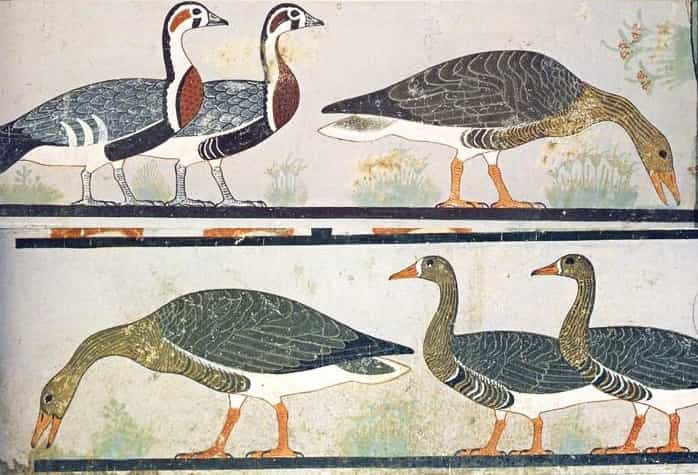

The pigments were obtained from different raw materials. Ground malachite was used to create the color green, iron oxide for red, natural ochres for yellows and browns, carbon for black, white was obtained from chalk or gypsum, and blue was obtained from an artificial mixture of calcium and copper.

These pigments were mixed with water and egg white to increase adhesion, and on some occasions during the New Kingdom, beeswax was used to give it a greater shine.

Ancient Egyptian painters chose colors so that the background was clearly distinguishable from the drawings, as the images were often charged with magical meaning. Additionally, men were painted with a more reddish hue, while women were painted in a yellowish color.

Painting in ancient Egypt: A brief history

In this article, we will take a brief tour of the painting of Ancient Egypt.

In the pre-dynastic period (end of the 5th millennium BC – 3200 BC), we find paintings on cloth, such as those found on the Gebelein fabric. In the few fragments that remain of this linen cloth, we can see different ships.

We also have painting on ceramics, particularly in Nagada II, where stylized images of boats and animals can be seen. During the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BC), we observe an evolution of painting. For example, in the tomb of Nefermaat in Meidum, a scene of geese is represented, being the first example of a complete sequence.

During the First Intermediate Period (2125-2055 BC), we have representations in the tombs of the nobles of how they carried out daily activities or storage.

In the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650/1640 BC), the practice of marking social position through size in painting becomes more prominent; for example, a nobleman appears in the paintings of a larger size than the servants or peasants.

During the Middle Kingdom, offerings and magical formulas that appeared on sarcophagi and walls were accompanied by figures of offerers so that the deceased would always receive those offerings in the afterlife, at least magically.

During the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC), the Amarnian period stands out. After Akhenaten‘s religious reform, ancient Egyptian art also changed, becoming much more naturalistic and realistic than it had been until then. The decoration of palaces at this time is a decoration of paintings, among which scenes of swamps stand out. After the Amarnian period, traditional aesthetic canons were recovered.

In the New Kingdom, the nobles are represented in their tombs in the same style as the pharaohs. From the Third Intermediate Period (1069-715 BC), paintings on papyrus began to be increasingly rare, with only some fragments of the Book of the Dead remaining.

Source: María González Rodríguez, historiaeweb