Depicting Pharaoh Khafre, son of Khufu, at the height of his power, this splendid 4,500-year-old work of art is considered a masterpiece of Egyptian statuary. Although it was made not to be seen, today its beauty continues to fascinate travelers who visit it in Cairo.

A surprising discovery

The statue, which with its half smile seems to contemplate from the abyss of millennia the astonished visitor who sees it for the first time, was discovered in 1860 by the Frenchman Auguste Mariette, then head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, during excavations in Giza.

The Egyptologist was excavating the funerary complex of Khafre, specifically the Monarch’s Valley Temple (which he himself had discovered in 1852), an enclosure where the purification ceremonies of the sovereign’s mummy took place before it was taken to the high temple, located next to the pyramid, through a long ceremonial causeway.

The Valley Temple of Khafre is 500 meters from his pyramid and is located near the Great Sphinx. The building has a square floor plan and its walls (which do not show any type of decoration) are covered with red granite slabs and the pavement is white limestone.

In it, the ancient Egyptians arranged an ambitious iconographic program consisting of a set of 23 statues representing Khafre. They all had religious significance.

They were to serve as a receptacle for the ka or life force of the deceased pharaoh. Much later, some of these statues were buried in a pit that was covered with stone slabs, and it was there that, centuries later, Mariette discovered them.

The Egyptologist wrote in his diary: “These are seven statues representing King Khafre. Five of them are mutilated, but the other two are complete. One of them is in such a state of preservation that you might think it came out of the box yesterday”.

The power of the pharaoh in stone

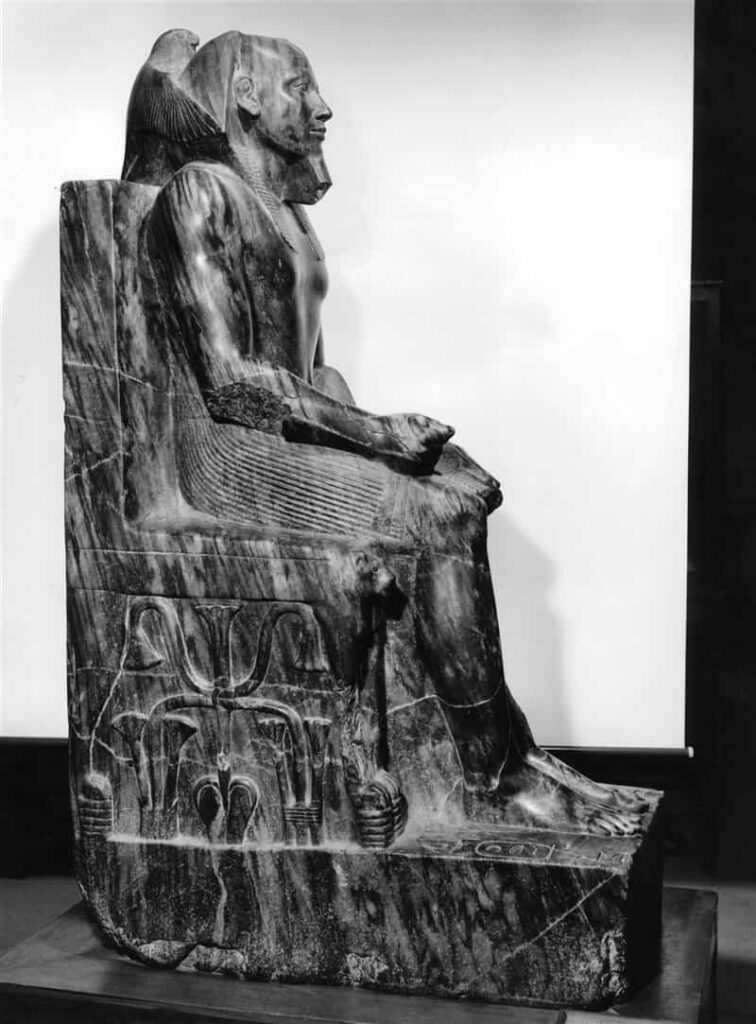

This work of art, made to be seen from the front, measures 1.68 meters high, 57 centimeters wide and 96 centimeters long.

It represents Khafre, pharaoh of the 4th dynasty and architect of the second largest pyramid of Giza (the largest is the one built by his father Khufu), a monument that still preserves part of the original limestone cladding on its apex.

The statue shows Khafre as a young man with a perfect, athletic physique, dressed only in a kilt, wearing the ceremonial nemes headscarf and the false beard characteristic of his position (which is broken). His face sketches a faint smile and his gaze is lost in infinity.

Behind the pharaoh, a falcon, a representation of the god Horus, a divinity with which the monarch identified himself in life, spreads its wings around Khafre’s head, offering him its protection.

The king’s arms are glued to the body and he places his left hand extended on his knee. The right hand, also on the knee, is clenched into a fist and appears to be holding a scroll of papyrus, a symbol of his power.

For its part, the throne on which Khafre is seated is finished off with legs in the form of lion claws and its sides are decorated with the symbol of the “sema-tauy”, the intertwined lotus and papyrus plants.

A new home

Khafre’s statue was first brought to the Bulaq Museum, the forerunner of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, to later be transferred to the museum that was set up in Tahrir Square.

In September 2017, the statue of Khafre, which until then had been the star of one of the rooms on the ground floor of the museum, was carefully packed, along with other large pieces, like it, and placed in a box with sensors.

With great care, it was placed in a specially prepared van with special devices to avoid the vibrations typical of transport, and it was transferred to its new home, the Grand Egyptian Museum.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic