Since the 1920s, archaeologists have unearthed small blocks of sandstone at the Temple of Amun in Karnak, decorated with beautiful scenes that preserve their original polychromy.

These scenes were part of larger ones that decorated the defunct temple built by Akhenaten in Karnak, the Gempaaten, dedicated to the solar disk. But what happened to that great temple? And, more importantly, why were its decorative elements used by his successors as filler rubble in later buildings?

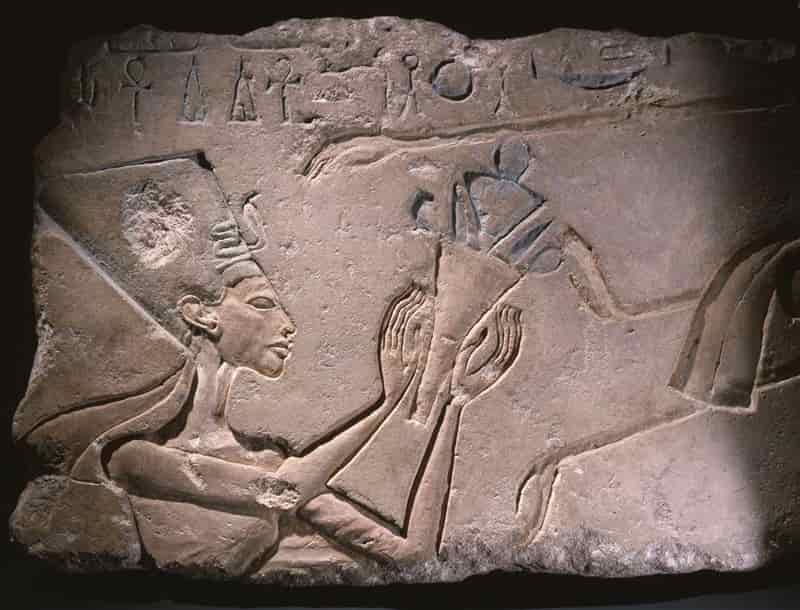

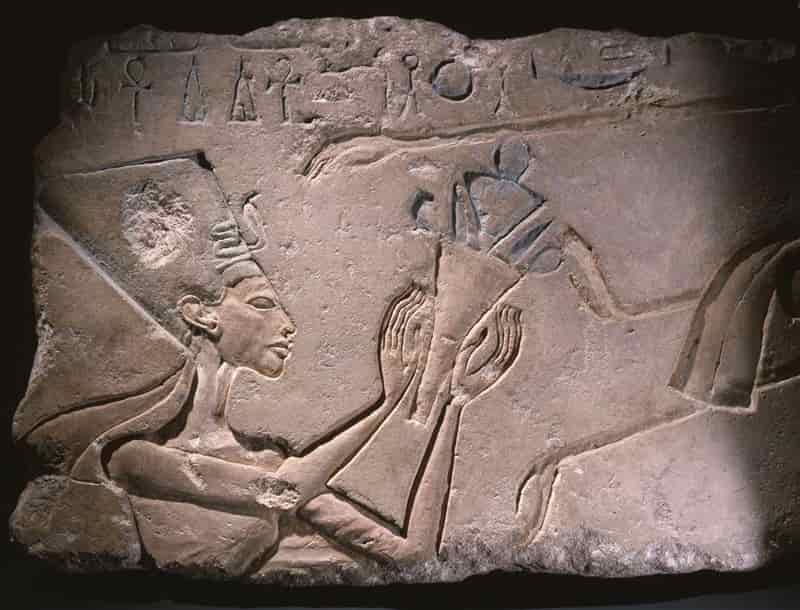

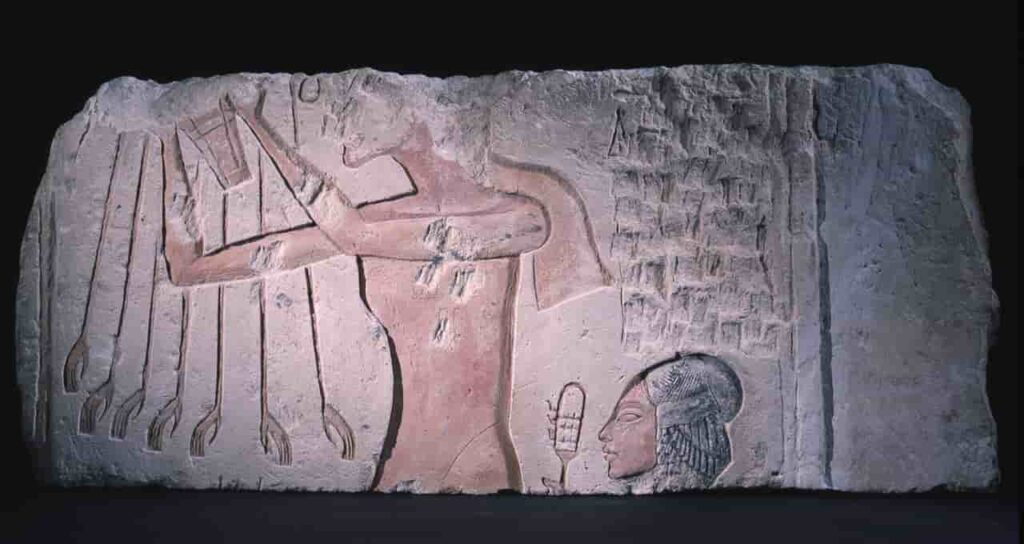

The powerful rays of Aten, the solar disk, mercilessly bathe those attending the inauguration of the great temple dedicated to the god in Karnak, the Gempaaten.

Celebrating the ceremony is Akhenaten, the new pharaoh of Egypt, who has just changed his dynastic name, Amenhotep IV, to a new title that includes the name of the solar disk, the divinity that from now on will become hegemonic in Egypt.

The temple dedicated to Aten has no roof. Thus, the sun’s rays can travel without restriction the entire extension of the sanctuary and caress with their warmth those who come to venerate Aten.

Especially his son, Pharaoh Akhenaten, who raises his arms to heaven while singing the Hymn to Aten, addressed to his divine father and composed by himself:

“You appear full of beauty on the horizon of the sky, living disc, that you start life. By rising above the horizon of the Levant you fill the countries with your perfection …” .

Akhenaten would end up moving the capital of the country to Amarna, in Middle Egypt, where the pharaoh raised a great city out of nowhere with beautiful palaces and magnificent temples destined for the greater glory of the new main god of Egypt.

But before leaving behind Thebes and the clergy of Amun, until then possessed of absolute power, Akhenaten had ordered to raise the Gempaaten in the sacred precinct of Karnak, domain of the god Amun, to the horror of his priests.

But Akhenaten’s religious revolution did not survive him, as did almost none of his works. In fact, the memory of the pharaoh and his family was subjected to a systematic erasure. Ancient Egypt wanted to forget the years of Akhenaten, the cursed pharaoh, the heretic … Another era was beginning.

Temple of Akhenaten: Erased from history

The indisputable proof that someone tried to erase the memory of the pharaoh forever would appear thousands of years later, in 1926, during a restoration program in the Karnak temple carried out by the French archaeologist Henri Chevrier, at that time inspector of antiquities of the Upper Egypt.

While studying some of the pylons in the temple of Amun, he recovered no less than 20,000 small blocks of sandstone, uniformly cut and about 50 x 25 x 23 centimeters.

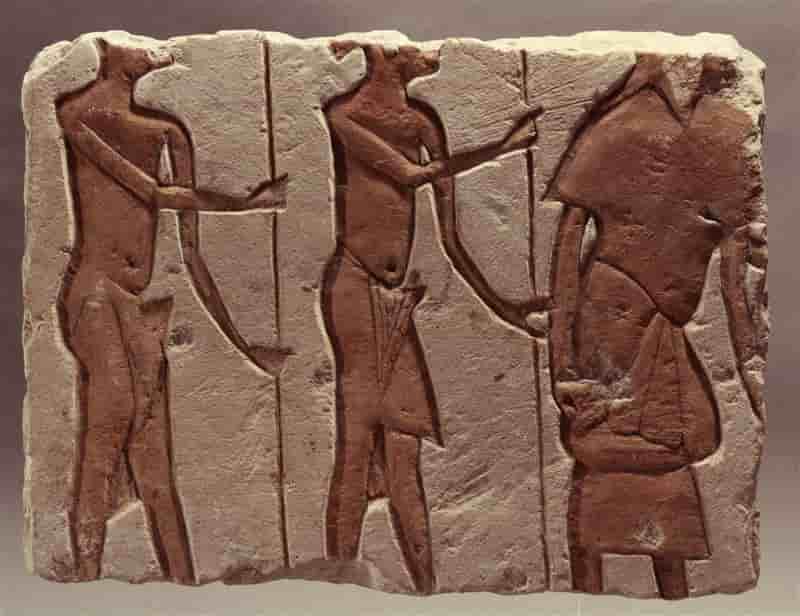

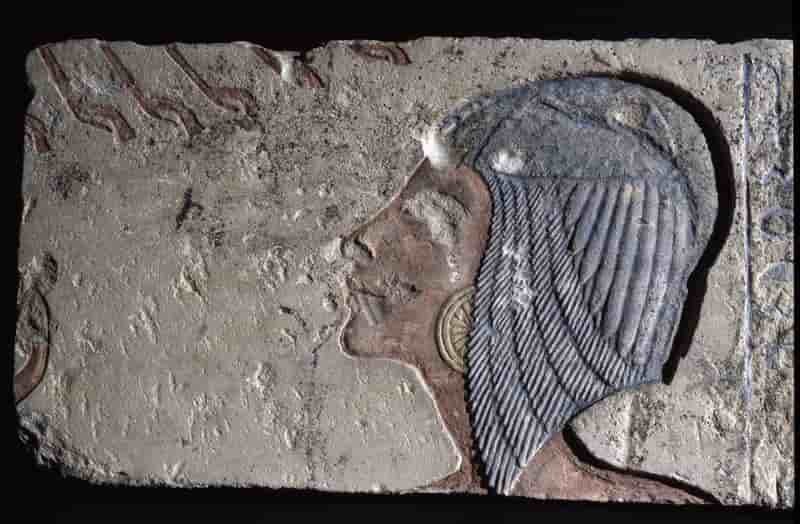

Many preserved remains of paint and others were decorated with reliefs that seemed to be part of much larger scenes. Because of their size, three hand widths long, the workers baptized them as talatat, which in Arabic means “three.”

Chevrier also found remains of broken masonry at Karnak with the inscribed name of Amenhotep IV. The archaeologist concluded that these masonry fragments and the thousands of “talatats” unearthed inside the pylons must have been part of a demolished temple.

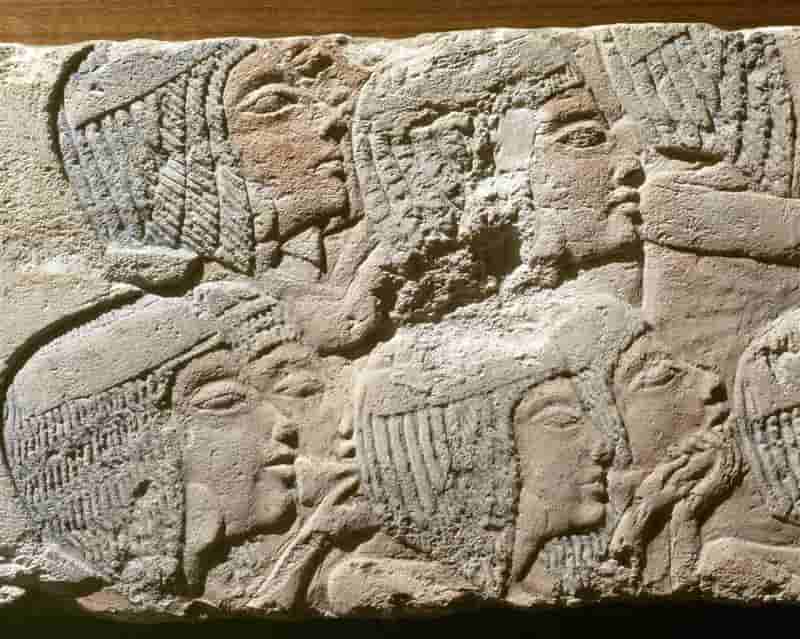

But there was something strange about it all. The blocks appeared to have been carefully moved from their original position, and many scenes depicting portraits of the royal family (Akhenaten , his wife Nefertiti, or their daughters) had been intentionally damaged. It was clear that this was all part of an orchestrated campaign of destruction.

But rebuilding the great temple of Aten was a daunting task, far beyond Chevrier’s capabilities at the time. The archaeologist then ordered to store the thousands of talatats, many of them on wooden loading platforms, without any type of protection.

The stones were gathered without registering their original positions, at random, which greatly complicated their possible assembly in the future.

During the following years more talatats kept appearing, but they were simply stored together with the others. Many mysteriously left Egypt and reappeared in private collections and museums around the world. Others just got lost.

A 100,000-piece puzzle

In 1965, Ray Winfield Smith, an American diplomat fond of Egyptology, proposed using scale photography to try to solve the puzzle that represented the 100,000 pieces that had been recovered from between the walls and foundations of pylons and structures in Karnak (specifically the Most of it was used as filling material for pylons 2, 9 and 10, built by Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, and also in the foundations of the great hypostyle hall, started by Seti I and finished by his son Ramses II).

Winfield, with the support of the Egyptian authorities, initiated the Temple of Akhenaten Project, sponsored by the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania.

The idea was to take thousands of photographs of the blocks and try to find the proper position of each piece to reconstruct a model of the original building. A real puzzle.

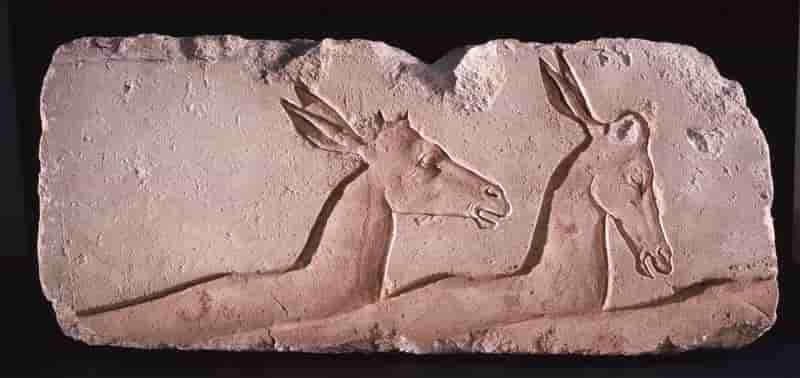

In 1972, the project was led by Canadian Egyptologist Donald Redford. To date, thousands of talatats have been matched, and many of the images that were represented in them have come to life:

Scenes of daily life that show workers and farmers doing their tasks, also carts with horses, representations of ceremonies and the royal family making offerings to the divinity, and even scenes from the first Sed or jubilee festival of Akhenaten, which the pharaoh performed between the third and fifth year of his reign. All captured with the realism and delicacy typical of Amarna art.

The Gempaaten was constructed outside the limits of the sacred precinct of Amun, towards the east. At the time of its construction, the sanctuary dedicated to the solar disk must have been larger than that of the tutelary god of Thebes (it must have measured 130 x 126 meters).

Apparently, the Gempaaten enclosure also included a royal residence. Forming part of the Gempaaten complex were other buildings as well, such as:

- Hwt benben (apparently dedicated to Queen Nefertiti),

- Teni-Menu (which contained warehouses and private chambers)

- Rud-Menu, whose function is unclear.

The talatats that were part of both the Teni Menu and the Rud Menu were discovered inside Pylon 9, built by Horemheb.The stone blocks were rescued and a large part of them could be rebuilt, as if it were a giant puzzle, and are exhibited today in the Luxor Museum.

An ancient mystery

But who orchestrated that gigantic campaign of historical erasure? Who went to the enormous trouble of dismantling all these buildings piece by piece and then using the fragments as fill for other buildings?

Everything points to General Horemheb, who was pharaoh after Tutankhamun and Ay. In fact, the erasure of the memory of Akhenaten and his successors had already been initiated by Ay, who even erased the name of his predecessor, Tutankhamun, from some inscriptions.

But it would be Horemheb who would undertake the daunting task of dismantling the Gempaaten and its outbuildings.

Thousands of years later, in 1978, Egyptologist Donald Redford discovered in a large pile of rubble the end of a pole that may have been lost by a foreman in charge of directing the demolition work. And that pole had a cartouche with an inscribed name that seemed to leave no doubt as to who commissioned this task: Pharaoh Horemheb.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic