The Army of Alexander the Great: Composition

The force that under the command of Alexander the Great invaded and conquered the Persian Empire, thus ensuring the extension of the Hellenistic culture to most of the world known at that time, was composed in total from 40,000 Experienced and well-armed fighters.

a) Cavalry

Heavy Cavalry: from 1,700 to 2,100 riders

It is not clear if the definition of “companion” came from the fact that they were “companions” of the king, which they protected in battle, as a type of royal guard, or from the fact that they were companions and equal among themselves, since they trained and lived together and were of more or less “noble” origin.

It was undoubtedly the elite force of the Macedonian professional army, a heavy cavalry of attack trained to strike the rear and the flanks of the enemies.

It was the “hammer” of Alexander’s tactics (the “anvil” corresponded to the phalanx).

Most of its components would not carry any protection, except helmets and breastplates of leather and pressed linen, but it was a force that exceeded in mobility the Persian cataphracts.

His typical formation was the wedge, which although it was not too flexible once the battle was started if it allowed them to make the most of their shock power.

His weapon was a long spear, the Xyston, 2 or 3 meters that was used without support, spearing the enemy with the unique strength of the arm.

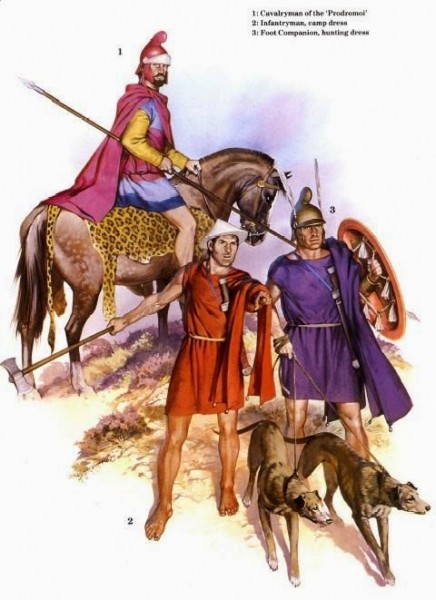

Macedonian light cavalry: 800 to 600 horsemen.

Macedonian cavalry equipped lightly, without using armor or any protection, except a Boeotian helmet.

They went before the main force (hence the name, “the precursors”). They were explorers, beaters, and protected the flanks of heavy cavalry, a kind of peltast on horseback.

Cavalry of Thessaly: from 1,700 to 2,100 horsemen.

The best cavalry of Alexander recruited among the semi-vassal territory of Thessaly that had historically stood out for the quality of its cavalry forces. Its type formation was a rhombus, with a delegated commander at each vertex.

This training gave them an enormous flexibility, since they could change their combat front from one vertex to another with a simple command.

The rest of the cavalries of the time knew only two maneuvers, the attack and the retreat, which gave the Thessalian cavalry a very remarkable advantage.

The Thessalians stood out for their costumes, a huge wraparound cloak and a helmet that imitated a travel hat. Their spears were almost certainly shorter than those of the Macedonian cavalry.

Allied Greek cavalry: from 600 to 750 horsemen.

Conventional Greek cavalry, possibly used as a reserve.

Cavalry Peony: from 200 to 300 riders.

They functioned as light Cavalry in the peltasta style.

b) Heavy Infantry

Macedonian Falangists: 12,000 men.

The base on which Alexander and Philip II articulated their battles. The phalanx usually had only one mission, which was to set the enemy front to allow the cavalry to locate the flank and the rear (the famous “anvil” of the Macedonian army).

Whatever they did, the enemy would leave an uncovered flank within reach of the cavalry or the phalanx.

The Macedonian phalanx of Alexander has been considered invincible, although a critical interpretation of the sources allows us to deduce that its war trajectory was not so brilliant.

It was a very inflexible training, because it had been created with a single purpose: to fix and crush the phalanx of the enemy in a frontal assault.

Since he sometimes had to fight superior enemies in number, and the Persian Empire stood out for the impressive numbers of his armies, Alexander recruited a large number of light infantry that would allow him to lengthen his flanks and avoid the risk of flanking.

They were troops who would have yielded against Hellenic hoplites, but who could hold the line against the light Persian troops.

Allied Greek Falangists: 7,000 men.

A minor force subordinated to the Macedonian phalanx.

Against this last one it would have been in inferiority given the smaller length of its spears and its small number, but possibly it was superior in the fight against the Persian forces due to the greater versatility that its shorter spears allowed.

Possibly its members had a more solid personal protection, since in the Macedonian phalanx the protection came from the long spears that were projected in front of the enemy, although the general trend in the Greek armies had been to lighten their hoplites.

This fostered the cohesion of the closed order, forcing the soldiers to keep close to each other in search of protection, while increasing the number of citizens susceptible to being recruited by making the equipment cheaper.

Being an elite force recruited from across Greece, they may still have a superior quality team.

Alexander used it as support of his own Macedonian phalanx, in The Battle of Gaugamela he had already decided that the Persian infantry had no chance of defeating his Falangists, although he still feared the possibility of being surrounded, so he placed the Greek allies in the rearguard to avoid this risk … although it is not clear how these would have been protected in turn from the same risk.

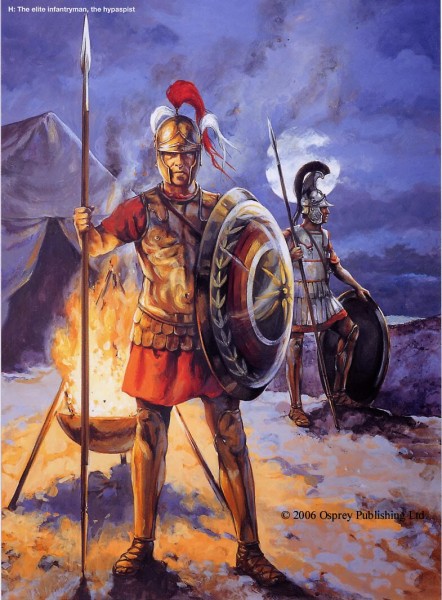

Macedonian royal guard: (Hypaspists: shield bearers, silver shields) 3,000 men.

The nature of this force has not yet been entirely clear to historians; one could take the simplest explanation as the most obvious: They were the infantry equivalent of the Hetairoi, the royal guard on foot.

Possibly it was a section of the phalanx formed by experienced veterans and that had a greater mobility to form a second front of spears before a danger of flanking (the biggest threat to a phalanx).

The hypaspists became known as argypappistes “silver shields” a distinction in honor of their capacity as a veteran and invincible shock force.

Even after the death of Alexander they maintain their number, 3,000 men, which reinforce their consideration of elite strength.

c) Light Infantry

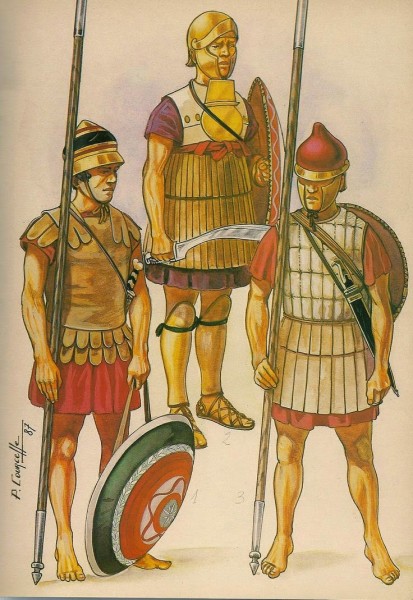

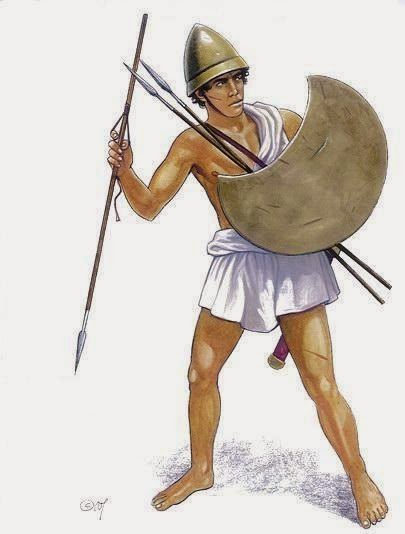

Peltasts:

Peltasts were what we could call Rangers, hunters, beaters. It was a very light infantry, endowed with javelins and light armament and responsible for obstructing as much as possible the enemy formation, even attacking it from a distance.

Thracians: 6,000 men

He would be a type of “barbarian” warrior dressed and equipped with his traditional weaponry.

Greeks: 5,000 men

The “civilized” equivalent of the previous combatant. The Greek peltast had always been a “lightened” hoplite, who gradually regained weight until after the reforms of the Athenian Iphicrates.

Their armament made them a versatile force, since they could form a firm battle line and resist the onslaught of the enemy.

This made them very useful to occupy strategic points on the battlefield and keep them until they were relieved.

Archers: 1,000 Illyrians, 500 Agrians with Javelins, from 500 to 1,000 Cretan Archers.

Several light troops, mostly throwing weapons that are used for skirmishes before combat or for support to the heavier troops, as in the case of archers.

Operational capabilities

The Macedonian army stood out against the classic armies in three main aspects:

1- It was a professional and permanent army, born of “feudal” type commitments with a leader who did not have to respond to any type of collective control institution.

2- Its experience was so abundant in the fight against irregular forces (Thracians, Tribes, Illyrians) as against the organized armies.

3- Its recruitment was based on an entire nation of considerable size, compared to classic army that was limited to a city and its small hinterland.

In front of the Persian army it stood out for the homogeneity and the organization, and for the superior quality of the tactics and the armament.

As if that were not enough, it was supported, for the first time in history, by an organized staff and an effective siege chain.

If the commander in chief considered it appropriate, military engineers could build heavy siege weapons in a very short time, and design a site with great chances of success.

For its part, the staff organized the supply and the routes of advance taking into account a rational study of the distances, the land and trying to harmonize it with the dates of collection of the crops to avoid the shortage of food.

Between 402 and 399 BC, an army of about 14,000 hoplites crossed the entire western front of the Persian Empire, without their armies could stop or defeat them.