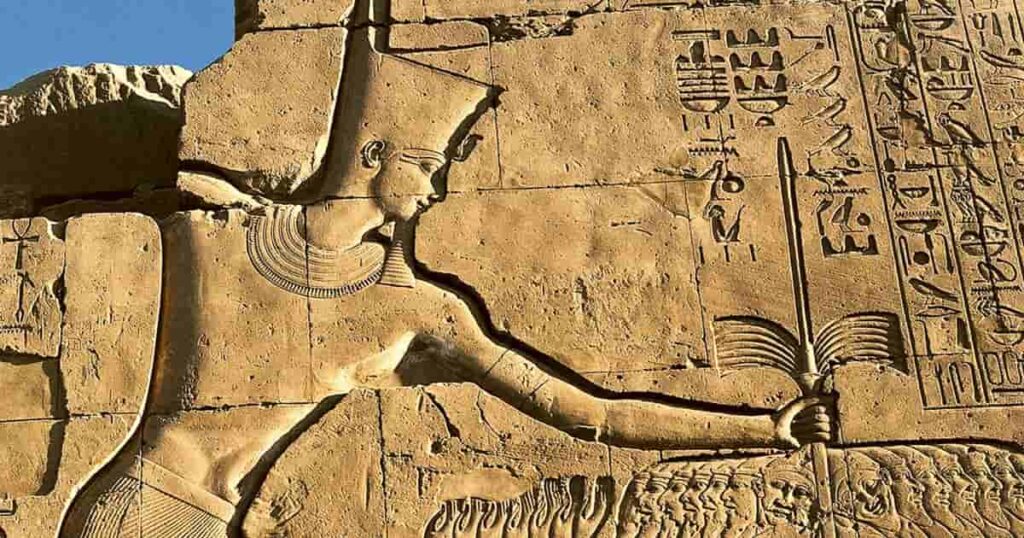

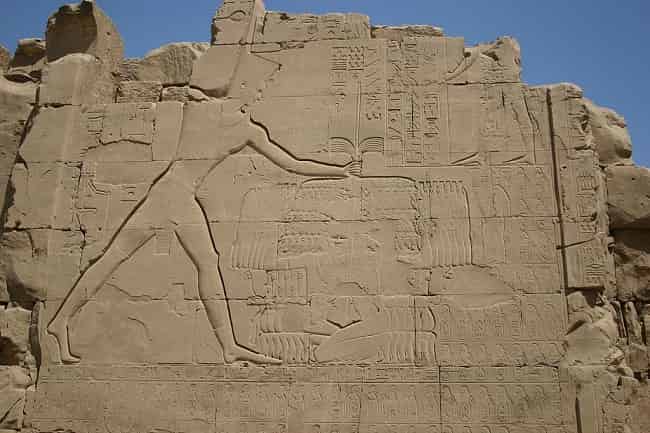

The pharaohs in Ancient Egypt carved images on the walls of their temples, presenting themselves as victorious leaders crushing their enemies.

Numerous inscriptions relating to conquered sites, chronicles of battles, and successful expeditions were discovered from the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC) when Egypt reached its peak.

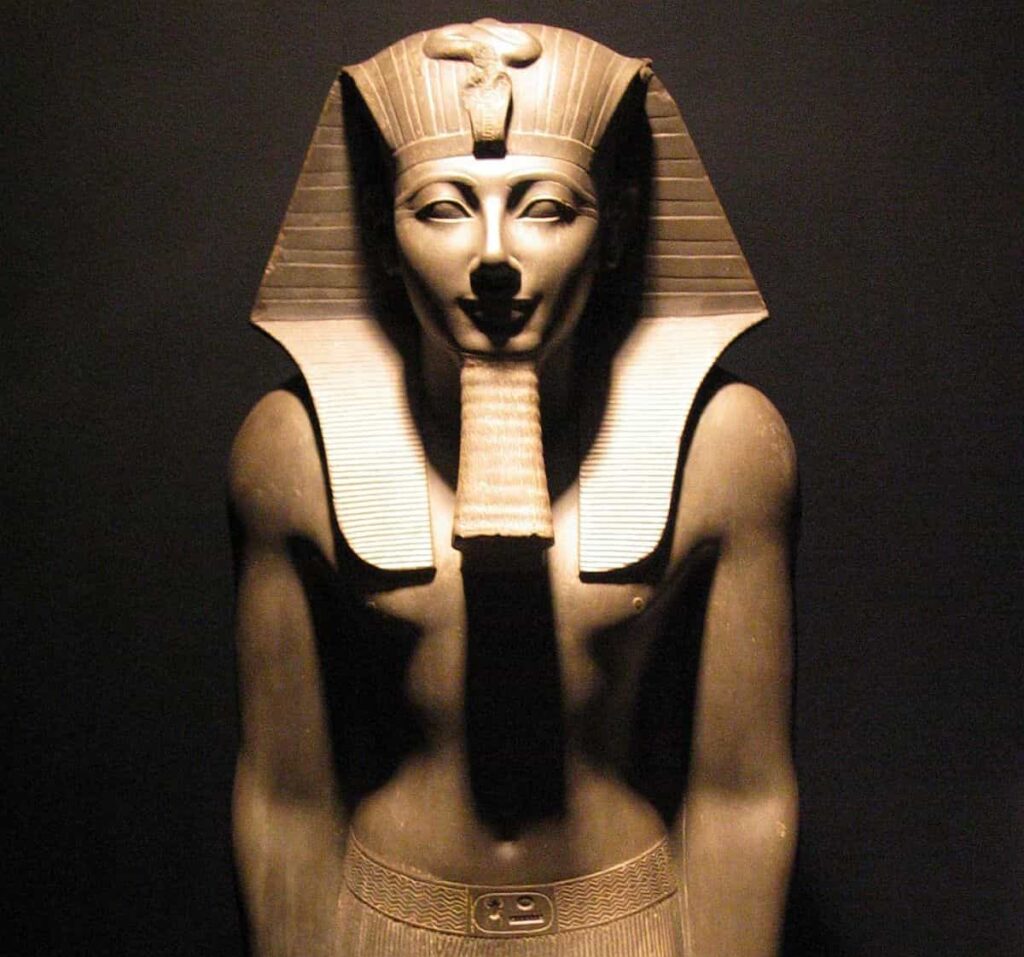

If there was a king who stood out in the military world, it was Thutmose III, who reigned between 1479-1425 BC – of which he reigned alone from 1458 BC (Hatshepsut ruled in his place the years previous).

Thutmose III was raised within the military establishment and received a prudent education in the art of war and the direction of an army.

As we will see below, this apprenticeship ended up converting him into the pharaoh who led Egypt to its maximum territorial extension.

Background in Egyptian foreign policy

Before discussing the campaigns of Thutmose III, it is worth making a brief review of the history of foreign policy in the new Egyptian kingdom.

This golden period arose after a series of military campaigns that freed the Egyptians from the rule of the Hyksos, who had controlled northern Egypt for a century.

Once this was achieved, Ahmose and Amenhotep I (1550-1504 BC, both reigns added) set the goal of expanding to the south.

First, the southernmost regions of Upper Egypt, affected by possible rebellions, were reorganized, and then Nubia was raided for its precious gold.

Thutmose I (1504-1492 BC) continued with these campaigns and achieved an unprecedented achievement in Egyptian history. He extended his borders to the fourth cataract of the Nile.

It seems that this pharaoh was the first to launch campaigns toward Asia, although their scope cannot be confirmed; for some, he was able to reach the Euphrates River, and for others, he did not even reach the Orontes River.

Still, he had set a precedent so that it would become the region that the pharaohs sought to control in the future.

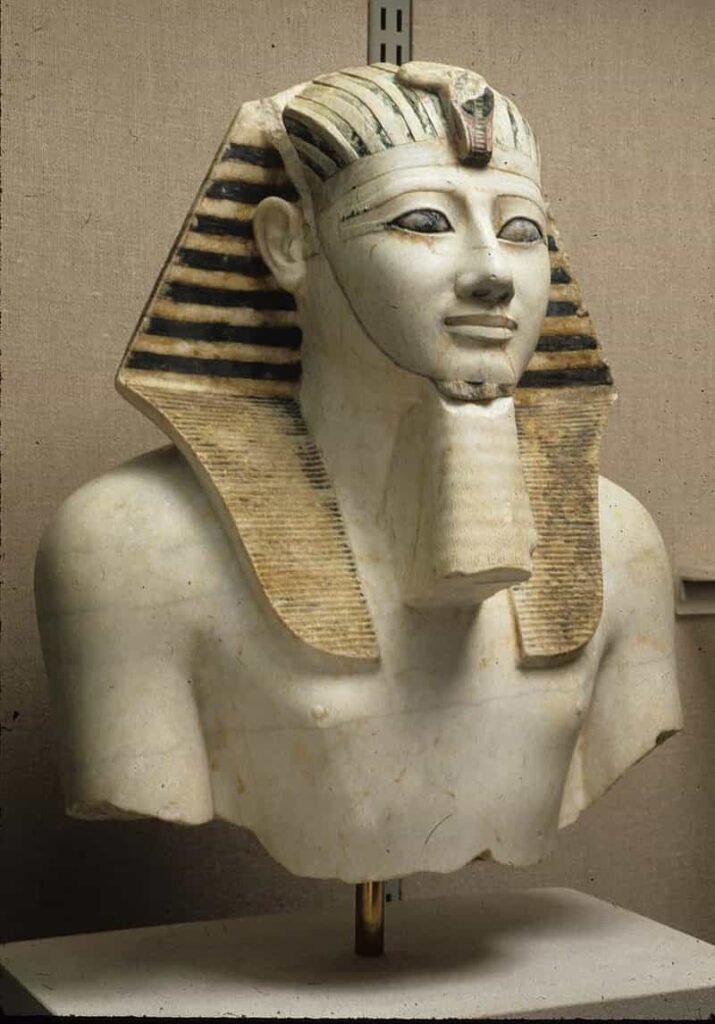

After the ephemeral reign of his son, Thutmose II, whose reign is unknown but presumed very short, his sister, Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BC), came to power.

This queen dedicated herself to maintaining what she had achieved in Nubia, and she did not seem interested in spreading toward the Mediterranean Levant.

It is very likely that ancient Egypt, at this time, did not have sufficient military capacity to enter this area of the Asian continent. More specifically, the area was under the influence of Mitanni, the first power in these lands, and the Egyptians did not want direct confrontation with them.

The campaigns of Thutmose III

When Hatshepsut died in 1458 BC, Thutmose III was able to start his reign alone at a relatively young age. From his aunt, he inherited an Egypt that was prosperous and economically and internally stable, which allowed him to focus on his greatest specialty: The army.

The ancient Egyptians had begun to adopt techniques and weapons that they had inherited from the Hyksos, such as the compound bow or the chariot.

These innovations coming from the Middle East added to Egypt’s economic potential and created a powerful army.

Thutmose III did not seem to be very interested in expanding in Nubia, although he made sure to maintain control and the inherited stability; in fact, only one major campaign is reported late in his reign.

It is possible that this is because he had as his main objective, the Egyptian expansion throughout the Mediterranean Levant, to control important commercial regions and achieve success where no other pharaoh did.

Thutmose III’s first major engagement was at the famous Battle of Megiddo against a coalition of city-states led by the Prince of Kadesh.

For the first time in history, we know with relative approximation what war was like because the campaigns of Thutmose III were recorded in his annals.

Thutmose III, the warrior, and ingenious pharaoh

The benefits of his first campaign, both in loot and prestige, led this pharaoh to embark on a campaign for control of the region from Mitanni.

In total, Thutmose III carried out a total of fourteen recorded campaigns, this number eventually extending to seventeen.

After the first of them (that of Megiddo), between years twenty-five and twenty-nine of his reign (counting the years of Hatshepsut’s regency), he launched a total of four campaigns to gain control of the current Syrian-Palestinian fringe, in addition to consolidating positions previously gained.

Between years thirty and thirty-three of his government, we find the most important campaigns as he managed to cross the Euphrates River and reach Mitanni lands. Egypt, thus, reached its moment of greatest territorial extension.

Thutmose III’s last military campaigns were between years thirty-four and forty-two of his reign. Here, he focused on defending himself from Mitanni’s counteroffensives and definitively conquering Qadesh.

Although the tension between the two empires remained, the remainder of Thutmose III’s reign was peaceful.

The imperial rule of Pharaoh Thutmose III

Egypt had expanded like never before, so it was necessary to establish an administration for the different territories that it had conquered.

In the case of Nubia, which had already previously been largely occupied, military occupation and the establishment of a governor were maintained to lead the region on behalf of the pharaoh. He intervened to protect the lucrative trade in Nubian gold, the most precious metal for the Egyptians.

On the other hand, the Mediterranean Levant presented greater difficulties in maintaining its control.

Although it is known that around 3,000 BC, the Egyptians had occupied the area militarily, by this time, it was already something very complicated; a vast network of city-states made military occupation difficult because it involved a large deployment that the ancient Egyptians could not execute.

For this reason, a policy of overthrowing local rulers was established to stop leaders related to Egyptian interests. Likewise, their children would be raised in the Egyptian court in order to align them in its orbit and reduce the chances of them rebelling.

This was a system that was in force throughout almost all of the New Kingdom with good results.

Source:

Alvaro Comes Cervera, historiaeweb

Delgado, J.M.S. (2021). Texts for the ancient history of Egypt. Chair.

Ortiz, JMP (2012). The Egyptian empire. RBA.

Pharaonic Egypt. Isthmus Editions.

Quesada, UJJ (2012). Pharaonic Egypt: Politics, Economy, and Society (2nd ed.). Salamanca University Editions.

Shaw, I. (2010). History of ancient Egypt. The sphere of books.