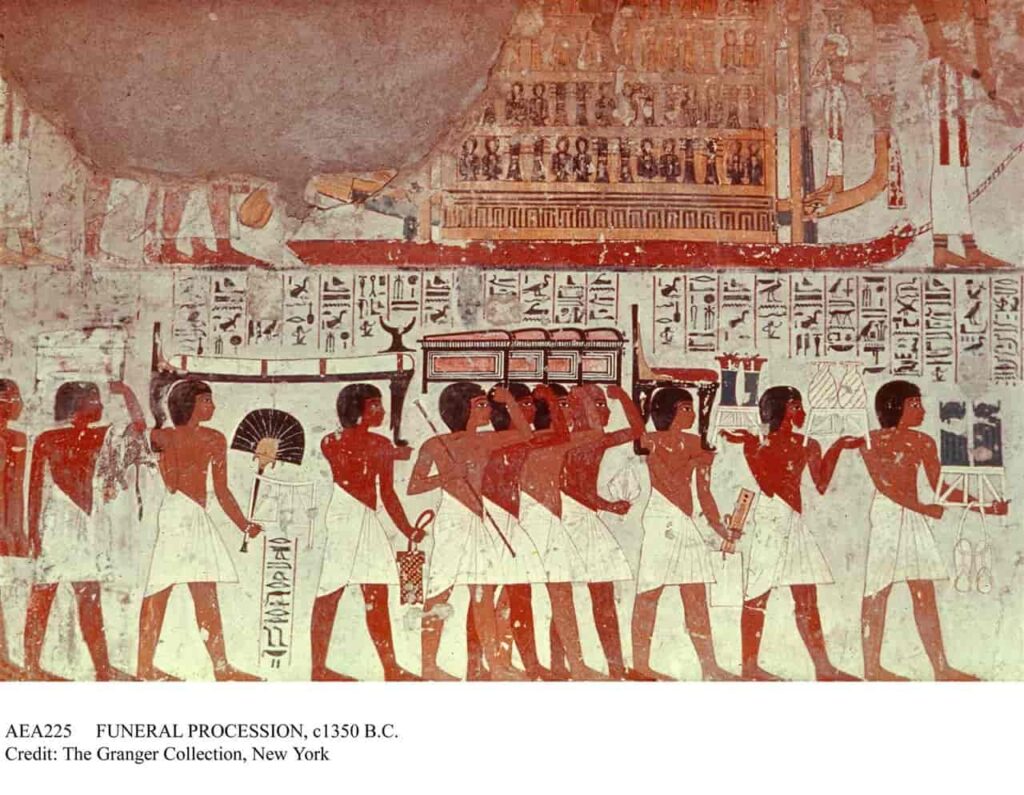

Despite the severity of the penalties imposed by the Egyptian courts, which punished tomb robbery with death, these were a constant in Pharaonic Egypt since time immemorial.

Despite what it may seem to us, not all Egyptians felt an almost sacred veneration towards their deceased kings, nor a superstitious fear towards the punishments, divine or human, that their impious acts could bring them.

In fact, grave robbers were noted for showing little respect for the dead and being completely unafraid of admonitions that tomb robbing was “a crime that the gods will never forgive those who commit it.”

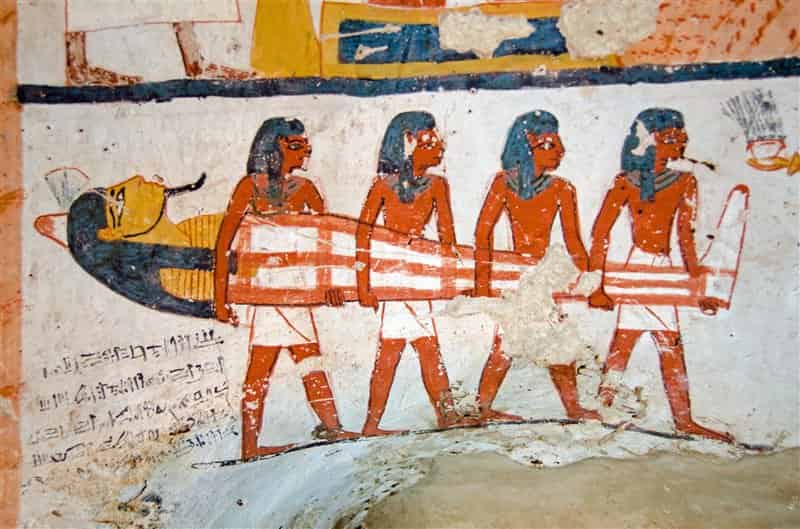

These men did not think twice if they needed light and to enlighten themselves they had to turn mummies into improvised torches to light the way, and they did not mind unceremoniously tearing the linen wrappings that covered the bodies of kings, queens and nobles in search of the coveted gold, even if for this they had to rip off heads and limbs, and then throw them away anyway.

Traps for thieves

The builders of the tombs took many precautions to avoid looting, but despite this, there are a rare Egyptian tombs that have not been looted.

In all of them, ancient thieves dug a tunnel or managed to penetrate inside by some other means. The architects of the pharaohs designed everything from locks to false passageways, sliding stone trapdoors and rubble-filled pits that were meant to entomb anyone who tried to enter.

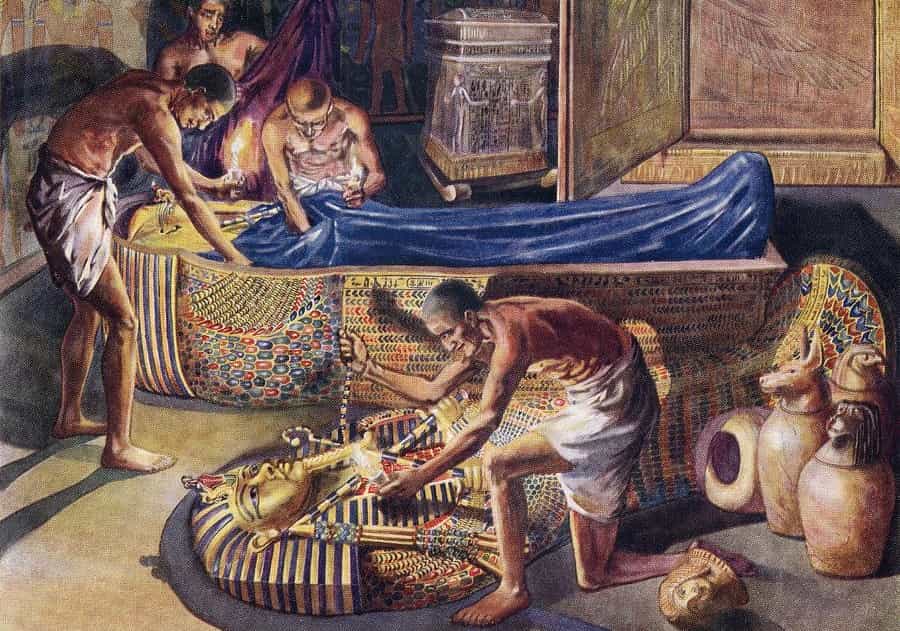

But there was at least one case where one of these traps did work. Thousands of years later, an archaeologist found evidence of a dead thief in the middle of “work”.

The investigator found a severed pair of arms on a broken coffin. The rest of the body was lying to the side. Possibly this man tried to lift the mummy from inside the coffin when the roof of the tomb collapsed, severing his arms and killing him instantly.

In fact, grave robberies increased in times of crisis. During the first intermediate period (2100-1940 BC), after the fall of the 6th dynasty of Egypt, the country experienced a series of altercations and uprisings that disrupted the social order.

A sapiential text of the time called (The admonitions of the wise Ipuwer) already warned: “Look at the looters everywhere” and “what the pyramid hid has been left empty”.

Caught up!

But thieves didn’t always get away with it. Many were caught and some confessed hoping for some clemency.

The Abbott, Amherst, and Leopold II papyri recount one of the most curious cases of tomb robbery that occurred at the end of the New Kingdom (1539-1077 BC), during the reign of Ramses IX.

At that time there was a veritable plague of looting in the Theban royal necropolises. Paser, mayor of Thebes, accused a certain Pauraa, mayor of Western Thebes, where the necropolises were located, of being an accomplice of the tomb raiders.

There was then a series of arrests and interrogations that ended up bringing to light a well-organized network of plundering the tombs of kings and nobles, involving important members of the administration.

The vizier took charge of the matter and several inspection visits were made to the necropolis to check the state of the burials.

Protect the mummies

The situation would worsen over time, and already during the 21st dynasty (1076-944 BC) it was decided to remove the royal mummies from their tombs and deposit them all together in caves to protect them from constant looting.

Many of these “caches” would be discovered centuries later by archaeologists, as is the case of the famous cache of Deir el-Bahari, in 1871, one of the most amazing finds in Egyptology.

Looting of ancient tombs continued over the centuries, and when archaeologists arrived in Egypt in the late 19th century, they found virtually no intact tombs.

Auguste Mariette, head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service from 1858 to 1881, tried to curb the looting and illegal excavations that still plagued the country.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic