The grave goods that Howard Carter found in 1922 in the famous tomb of the Valley of the Kings contained everything necessary to guarantee Pharaoh a peaceful and safe life in the Hereafter.

We would never have dreamed of something like this: a room – it looked like a museum – full of objects, some of them familiar, but others like we had never seen before, piled on top of each other in a seemingly endless profusion.

In this way, the British Egyptologist Howard Carter summed up the impression he had when looking for the first time through the crowded chambers of the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun, in November 1922.

It was the first time that anyone had contemplated a complete grave goods from Pharaonic Egypt, that he had not been a victim of the looters and thieves of antiquity.

Thus, the find not only uncovered a unique artistic ‘treasure’, it was also an incomparable opportunity to study and understand the significance of burial and life in the Hereafter for the ancient Egyptians.

Since prehistoric times, the Egyptians buried the body of the deceased along with objects that were considered necessary for survival in the afterlife: ceramic bowls (probably with food scraps), some ornamental element and utensils such as knives.

Soon the tombs of high-ranking characters were distinguished by the quality of their grave goods and by having a more complex structure.

At the same time, as religious thought developed, objects related to divinities and protection in the afterlife began to appear, such as amulets and statuettes of gods.

Its purpose was to protect the deceased from the dangers he had to face in the Hereafter and thus allow him to survive eternally. «Long live your “ka”, and may you spend millions of years, you, lover of Thebes, sitting with your face looking at the North wind and with your eyes looking at happiness ”, reads the inscription on an alabaster cup found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

For the ancient Egyptians, the body was made up of various elements, including the ka, a kind of double of the deceased who accompanied him in earthly life and who had to be fed in the afterlife.

Ka’s disappearance would cause the annihilation of the deceased, so the food offerings and part of the funerary equipment were intended for the conservation of the ka.

All of this was faithfully reflected in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Thus, upon entering the Antechamber, Carter found two statues that caught his attention from the first moment:

“Two life-size black figures of a king, facing each other like sentinels, wearing gold skirts and sandals, armed with a mallet and a staff and carrying on the forehead the sacred cobra as protection. One of these statues represented precisely the ka of Tutankhamun.”

The king, among the gods

Other pieces, meanwhile, evoked the divine condition of the pharaoh. Considered in life as the incarnation of the god Horus, at his death he became Osiris, the god of the world of the dead, a theme that appears evoked in the wall paintings of the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Numerous representations of divinities were also found in the form of statues and as decorative complements in some furniture, such as the beds destined for the regeneration of the pharaoh’s mummy.

Other pieces of the treasures, particularly abundant, consisted of amulets that the pharaoh wore as jewels. Their function were to protect the king from the dangers that haunted him during the night journey he made every night in Ra’s boat, the god of the sun.

Another element that could not be missing from the funeral trousseau were the ushabtis, figurines that represented the magical servants who continued to serve the pharaoh after his death to do their daily tasks.

Clothes, food and drink

An important need was the Clothes; hence the presence in the tomb of Tutankhamun of numerous linen garments, such as tunics, shirts, skirts, loincloths or gloves.

“In some cases,” Carter wrote, “the clothing is so strong that it looks like it has just come off the loom; in others, the humidity has reduced it to the consistency of soot.”

To drink, the pharaoh had amphoras of wine, each with the label that indicated the harvest, the class, the vineyard and even the name of the harvester.

As for food, Tutankhamun had basic foods –bread, garlic, onions and legumes, and even dishes prepared and stored in containers containing ducks or meats.

Crowns, thrones and swords

In the tomb of Tutankhamun were found several scepters heka (crook) and nekhakha (flail), symbols of royal authority and associated with the god Osiris.

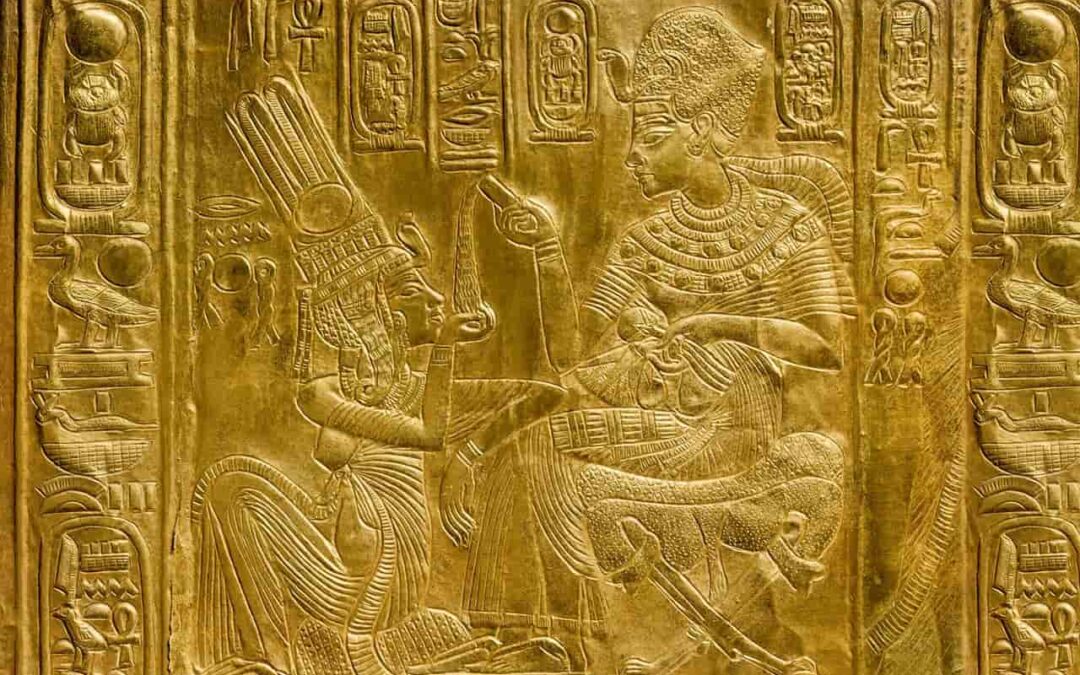

An important object that signaled Tutankhamun’s role as sovereign was the throne. Carter called it “another of the great artistic treasures of the tomb, perhaps the greatest we have uncovered so far: a throne covered with gold from top to bottom and richly adorned with glass, faience, and inlaid stones.”

In Ancient Egypt, chairs were a symbol of authority and prestige, and the throne was an example. Made of wood with a gold coating, the backrest presented an intimate scene, in which Tutankhamun appeared seated on a throne with his wife, Ankhesenamun, before him.

The scene was presided over by the solar disk, the god Aten, which with his rays gave life to the royal family. Ankhesenamun appears applying perfumes to the pharaoh’s body, in an intimate and everyday scene.

As one of the Pharaoh’s obligations was the defense of the country, it is normal that among the objects in his tomb there are a large number of weapons, both defensive (such as shields or breastplates) and offensive.

“It was seen that they had been placed in the tomb with Tutankhamun to assist His Majesty in combat with enemies who try to delay his advance from this world to the next,”.

Noteworthy are the curved bronze swords or khopesh, as well as the daggers. One of them is a rarity, since the blade was made of iron, a mineral little known in Egypt.

Throughout the tomb there was a great profusion of arches, both simple and compound; the measurements indicate that some of them were used by the pharaoh when he was still a child.

The human side of Tutankhamun

One fact that surprised archaeologists was that some of the objects discovered did not originally belong to Tutankhamun. In fact, most of the jewelry found in the tomb had been made at the time of his parents and even his grandparents, and Tutankhamun had simply changed the inscriptions that indicated the owner.

For example, a breastplate kept in a box has a cartouche too long for the name of Tutankhamun, so it follows that the name that was originally inscribed was that of Akhenaten, his father.

Read more: The discovery of Tutankhamun in full color

Source: Maite Mascort, National Geographic