Introduction

The Battle of Megiddo was a war that pitted the army of the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III (1479 – 1425 BC) with a military coalition of city-states from the Syrian fringe led by Qadesh and supported by the kingdom of Mittani in mid – 1457 BC.

This confrontation is contextualized, on one side, in the 18th Dynasty (1550 – 1295 BC), within the Egyptian New Kingdom, and on the other side, in the kingdom of Mittani, the most powerful state of the Near East of the 15th century BC.

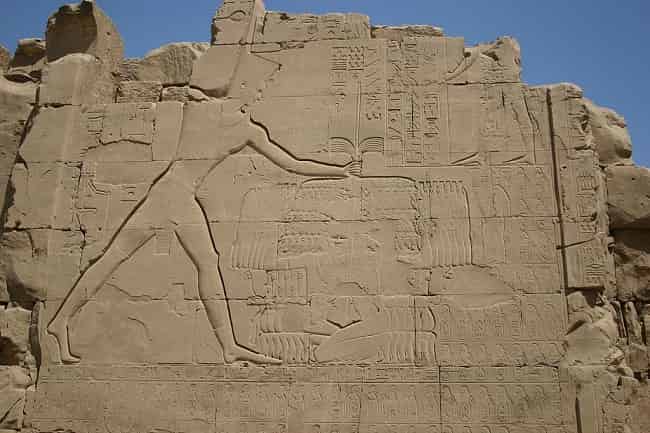

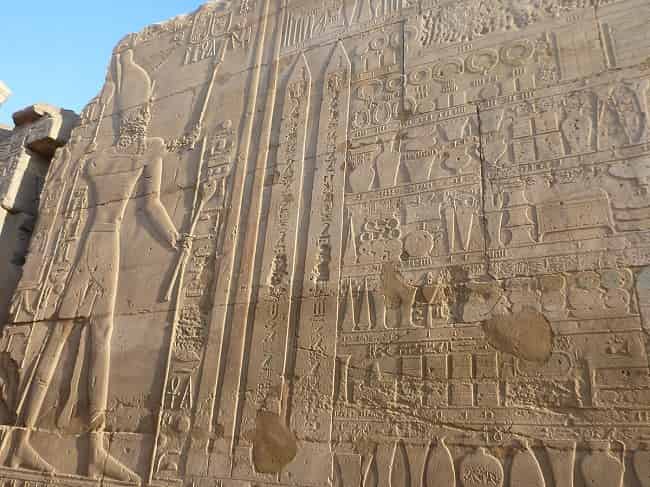

The exceptional character of the Battle of Megiddo lies in the fact that it is the first recorded battle in history. This battle, and in general, all the military campaigns carried out by Thutmose III in the Syrian strip (at least a total of fourteen), are narrated in great detail on the walls of the sanctuary of Amun in the temple of Karnak.

All are known thanks to the fact that the king’s scribes kept a meticulous campaign diary on leather scrolls, which was later copied on the walls of the temple.

In these inscriptions, called the Annals of Thutmose III, Pharaoh’s battles are exhaustively narrated, also describing the enemies they faced, the spoils of war they obtained, or the tributes that the defeated had to deliver to the victorious Egypt.

Background to the Battle of Megiddo

To better understand the political causes of this battle, we have to go back a few years in time. Hatshepsut (1473-1458 BC), stepmother and aunt of Thutmose III, was one of the few women who reigned with full power in Ancient Egypt.

The origin of this power came from the minority of her stepson and nephew, who at the time of being crowned after the death of his father, Pharaoh Thutmose II (1492-1479), was still a very young child.

In general, it is usually considered that her reign was quite peaceful, in contrast to that of her successor, since we have no sources of knowledge that tell us about military campaigns to the south or north.

Perhaps wanting to take advantage of this situation, upon the death of Hatshepsut, several Syrian city-states decided to turn their backs on the Egyptian kingdom that had dominated them until now and show their loyalty to the kingdom of Mittani.

For this reason, before he completed a year of reign alone, Thutmose III had to embark on his first and most important military campaign in the Levant.

The other side, the one supported by the Mitanni kingdom, is much more unknown. Since the middle of the third millennium BC, several Hurrian city-states had sprung up in Upper Mesopotamia.

During centuries there were several attempts to unify them, but it was not until the end of the seventeenth century BC when they were unified in a kingdom that in sources call it Mitanni (its official political name), Khurri (as it was called by its population, the Hurrians), or Khanigalbat (for the geographical area in which it was located).

Development of the Battle of Megiddo

As the story of the temple of Karnak recounts, not long after setting off for the Syrian region, Thutmose III realized that he could reach the place where his enemies gathered, Megiddo, by three different routes.

Two of them were longer but safer and more comfortable, since the paths were wide and the necessary precautions could be taken to avoid setbacks.

On the contrary, the third of them was shorter but also much narrower, which meant that his army could only pass single file and without comforts.

It also had a key element: It would allow them to get much closer of the city without being detected by the other side.

Despite the meeting he had with his generals, in which they recommended that he take any of the long ones, Thutmose III decided to risk his army and travel the narrow way.

After making their way smoothly, Pharaoh’s army turned up one morning on the plain in front of Megiddo, a few hundred yards from where the Asian coalition was camped overnight.

Counting on the surprise factor, the troops of Thutmose III launched a frontal attack against the side led by the king of Qadesh that quickly led to an Egyptian victory .

However, the pharaoh’s soldiers made a big mistake. When they saw the Asians flee, the Egyptians abandoned their weapons and began to loot the belongings left by the other side in their camp.

In this way, the remnants of the military coalition were able to reach Megiddo and strengthen their resistance. The serious mistake of the soldiers of Thutmose III had its consequences, since they needed to carry out a siege of more than six months to the city so that it finally surrendered and accepted Egyptian rule.

Aftermath of the Battle of Megiddo

After this first campaign, Egypt once again consolidated itself as one of the great powers of the region. The successive expeditions that Thutmose III carried out in the region in the following years were mainly of a collection nature, so that they would not forget to what great power they owed loyalty.

Even in the reign of his successor, Amenhotep II (1427 – 1400 BC), the raids were more reaffirmation than conquest.

Later, when both the Egyptian and Mitannian borders were threatened by a common enemy, the Middle Hittite Empire, the old enemies reached an agreement: Aleppo, Mukish, Niya and Nukhashe would be for Mitanni, and Qadesh, Ugarit, Tunip and others southern cities would be for Egypt.

On the other hand, after paying homage to him as the victor, owner and lord of the territory, the rebel cities provided Thutmose III with a booty of outstanding dimensions, collected in detail in the Annals of Thutmose III.

It included about 900 chariots (including two lined with gold), about 200 armor (including bronze of the rulers of Megiddo and Qadesh), about 2500 horses, more than 25,000 diverse animals …