The burning question historians keep trying to answer.

For a historical figure as well-known as Cleopatra, it’s odd that we really have no sense of what she looked like.

The muse for so many artists, poets and writers over the centuries, the true visage of the last pharaoh of Egypt is muddied by both time and inaccurate repetition.

Thanks to being on the wrong side of the Roman civil war, it’s believed that many examples of contemporary portraits of her were destroyed by Octavian, Julius Caesar‘s heir.

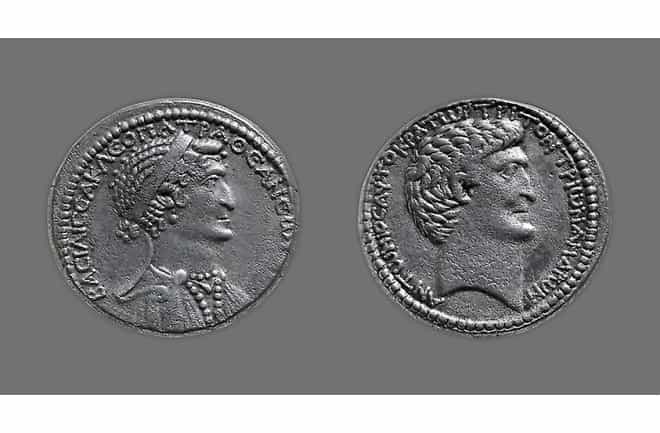

What we’re left with is around ten coins (approved for distribution by Cleopatra, so questionable in accuracy), a handful of statues (most in very stylised forms, so difficult to judge) and some contemporary accounts of her appearance (mostly contradictory).

But historians continue to pick away to find the truth. What we can be confident in saying is that she was not Egyptian, having been born to the Macedonian Ptolemaic line, but it’s also unlikely that she looked like a contemporary Greek. Her family line had lived in Egypt for 250 years, after all.

For our own recreation, we turned to the research of Dr Sally-Ann Ashton, an Egyptologist who worked on a more recent rendering of Cleopatra.

Her work, which contributed to a BBC documentary called Cleopatra: Portrait Of A Killer, drew from statues and an understanding that she would very likely have had mixed Greek and Egyptian heritage.

But is this all a distraction? While her racial background and depiction is of contemporary interest and relevance, the obsession with Cleopatra’s looks, whether she was the most attractive women in the world or ugly, were not that relevant to her ability as a ruler.

Much of the debate around her appearance in her own time was to push the conversation away from her keen political acumen; to diminish her legitimacy to rule. It was easier to think of her as a seductress than as a shrewd political operator.