In Egypt, archaeologists have unearthed millions of ibis mummies over the years, which were buried in special catacombs designed to house the mummified bodies of these beautiful birds.

Most have been found, for example, in Tuna el-Gebel, in Middle Egypt, where four million of these mummies have been found, or in the necropolis of Draʻ Abu el-Naga’, in Upper Egypt, where they have been discovered thousands of mummified ibis.

But where did such a huge number of ibis come from? That’s what a team of researchers led by paleogeneticist Sally Wasef of the Australian Research Center for Human Evolution at Griffith University has asked.

And they believe they have found the answer. The results of this study have been published in the journal PlosOne.

Were they hunted on a large scale?

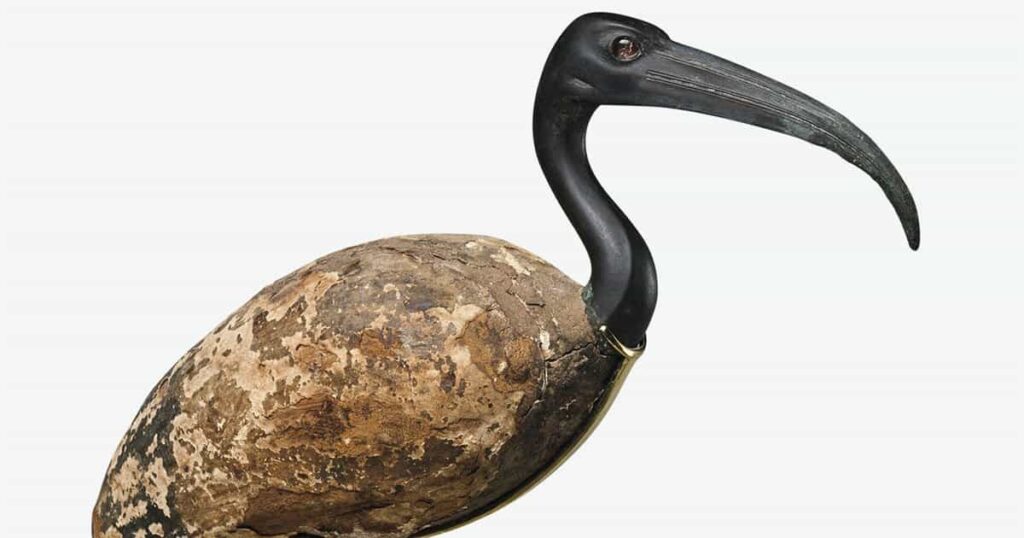

Between 650 and 250 BC, the ancient Egyptians sacrificed millions of ibis – of the species Threskiornis aethiopicus, the African ibis – which were later mummified to be offered to Thoth, a deity often depicted with a human body and ibis head who was the mighty patron of scribes and god of writing.

These mummies were offered to Thoth to ask for health or a long life.

Some ancient texts seem to indicate that the Egyptians raised ibis on an industrial scale, in facilities designed for that purpose – in a similar way to modern chicken farms – to satisfy the enormous demand for mummies of these birds on the part of the temples, which sold them to the pilgrims, which was a lucrative business.

This is indicated, for example, by a document from the 2nd century BC in which a priest and scribe from the town of Sebenitos, in the delta of the Nile, called Hor, tells that he regularly fed thousands of ibis “with clover and bread.”

But to date, researchers have not been aware of how the ancient Egyptians managed to gather such a huge number of these birds.

Thus, to try to solve the enigma, Sally Wasef’s team has analyzed the genomes of 14 mummies of 2,500-year-old sacred ibis from six Egyptian catacombs (including Saqqara and Tuna el-Gebel) and those of 26 specimens modern from all over Africa to compare them.

Genetic diversity

To their surprise, they saw that the genetic diversity of ancient birds was almost the same as that of modern ones. If the birds had been raised on special farms, the genetic diversity would have been very low due to inbreeding.

Wasef believes this would demonstrate “in all likelihood that priests domesticated wild populations through techniques such as tempting them with food within their natural habitats, such as lakes or wetlands near temples.

This study sheds light on a ritual long practiced by the ancient Egyptians and how the priests obtained millions of sacred ibis to sacrifice annually. ” Consequently, according to this study, large-scale rearing of ibis would thus be ruled out.

But not all researchers agree with these conclusions. The archaeologist Francisco Bosch-Puche, from the University of Oxford, who has not participated in the study, believes that the birds were bred in captivity, as some ancient texts collect.

One of the pieces of evidence he wields is the signs of healed fractures and infectious diseases observed in some of the ibis mummies, which are very similar to those documented in modern populations of captive animals with little genetic diversity.

According to the researcher, these sick birds would not have been able to hunt or flee from predators in the wild, so they most likely received care.

Bosch-Puche does believe, however, that the food from ibis farms would have attracted thousands of wild birds that would have been hunted to fill the demand for mummies.

Although for archaeologists hunting would not be the main technique to obtain these birds. “We speak of millions of animals in different places throughout Egypt, so I am not convinced that they depended only on hunting wild specimens”, the archaeologist ditches.

What is clear is that the results of this genetic study contradict traditional ideas about how the Egyptians mummified millions of ibis.

But research on the DNA of these birds could also answer the question of why the sacred ibis became extinct in Egypt in the mid-19th century.

So far it has been argued that the loss of their traditional habitats could have been the main cause, but this does not seem to be the only answer, as these birds are highly adaptable.

As stated by Salima Ikram , Egyptologist and specialist in animal mummies at the American University of Cairo, “is part of a larger conundrum that has to do with human-animal interactions and their impact on the environment.”

Source: CM Muñoz, National Geographic