Who was Ramses I?

In reality, Ramses I was a man not destined to be pharaoh and was born into a prestigious military lineage from the Avaris region in northern Egypt.

His name was Paramesu, and he had a brilliant career in the Egyptian army. He rose to great heights of power, becoming a general during the reign of Horemheb, the last ruler of the eighteenth dynasty (1539-1292 BC).

Paramesu was a capable man who knew how to quickly win the trust of the pharaoh, who would end up appointing him vizier (chaty), the second most important position in the state.

Ramses I, the founder of a dynasty

Over the years, Horemheb found himself having to appoint an heir since he had not managed to father male offspring. He thought of Paramesu as the most suitable man to take charge of the destinies of Egypt.

Although he was no longer a young man, the general had a son, Seti, with which the dynastic continuity was assured. Thus, when Horemheb finally died, Paramesu succeeded him on the throne with the name of Ramses I.

But his reign was very short since he ruled only sixteen months before he died (apparently from an ear infection) at just fifty years old. He was succeeded by his son Seti I, who also had a son, the future Ramses II.

After his death, the old pharaoh was buried with all the ceremony and pomp that a pharaoh of ancient Egypt deserved in the tomb dug for him in the Valley of the Kings (KV16).

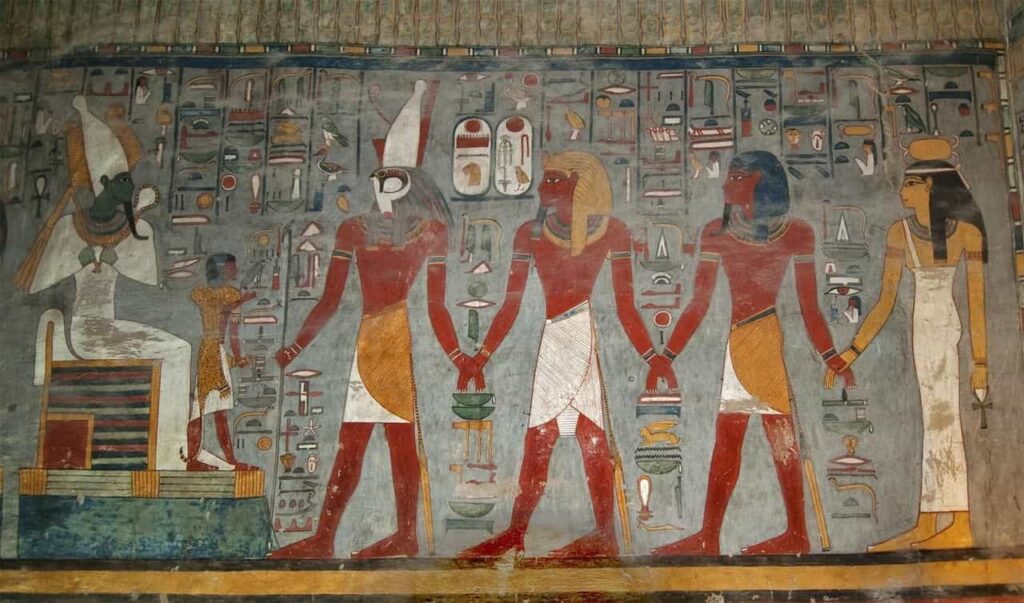

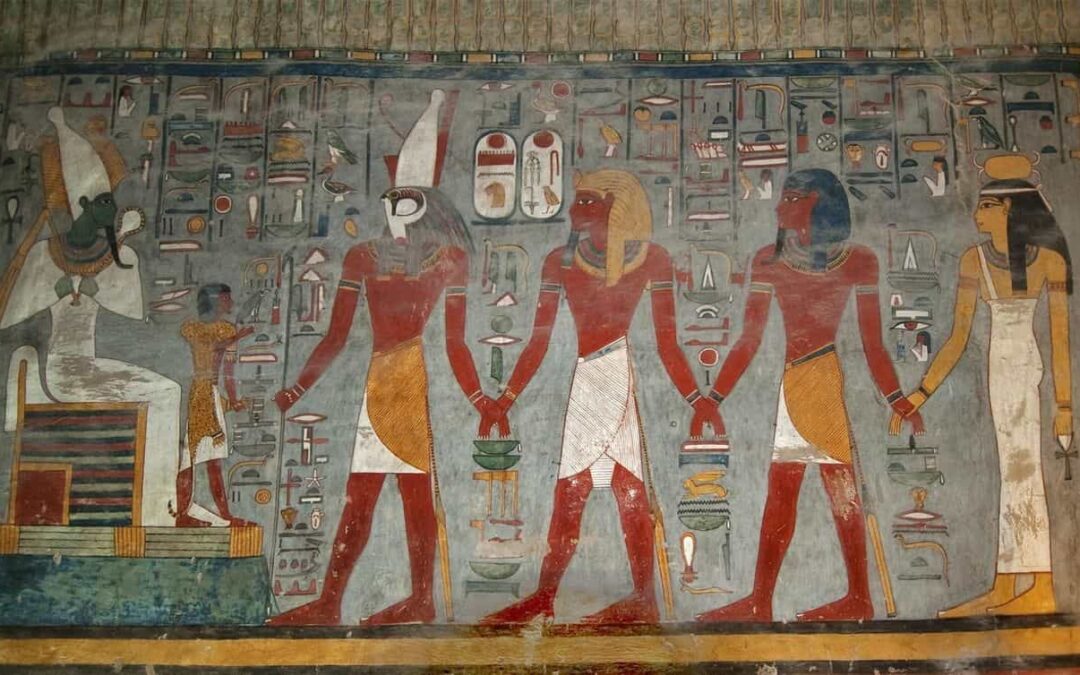

The tomb (which has recently been restored and opened to the public) was small in size, as there was no time to finish it before the King’s death, so only the burial chamber was decorated.

The priests and the transfer of mummies

In 1817, the Italian explorer and adventurer Giovanni Battista Belzoni entered the tomb of Ramses I but did not find his mummy there. So, where could he be?

The body of Ramses I enjoyed the tranquility of his tomb for approximately two hundred years before ancient Egypt was plunged into a period of great political upheaval; the Valley of the Kings suffered countless pillages.

In those years, the royal mummies were transferred from one place to another in search of safety by the priests of the twenty-first dynasty, in charge of protecting them from the avid hands of tomb robbers.

And the mummy of Ramses I was no exception. It was supposedly first transferred to tomb KV17, the tomb of his son Seti I, perhaps the most beautiful in the entire Valley. There, he would also be joined by his grandson, Ramses II.

But this would not be the final destiny of these three generations of pharaohs. The mummies of the three sovereigns were later transferred to the tomb of Queen Ahmose-Inhapy, from the seventeenth dynasty, and later, to the famous cache of Deir el-Bahari, the tomb of Pindejem II.

Although a large number of royal mummies were rescued from the famous cache, Ramses I was not among them. So, what had happened to him?

The mummy of Ramses I travels to the United States

The incredible cache of royal mummies had been discovered years ago. Not by archaeologists, but by a family of tomb robbers, the Abd el Rasul.

In 1871, through the Turkish trader Mustafá Ana Ayat, the Abd el Rasuls sold a remarkably well-preserved mummy to Dr. James Douglas, who in turn sold it to the Niagara Falls Museum in Ontario (defined as a “museum of monsters and curiosities of nature”), who exhibited it as the mummy of the legendary Queen Nefertiti, wife of the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten.

The return of Ramses I to Egypt

The royal mummy of Ontario remained in the museum for one hundred and thirty years until it went bankrupt in 1999. In 2001, it was sold to the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, near Atlanta.

In this institution, the unknown mummy was subjected to various studies, and finally, the researchers from the University announced that they could say with certainty that it was the mummy of Ramses I.

The careful and costly mummification process to which the mummy had been subjected convinced the experts that it was a real mummy.

In fact, a CT scan performed in the Department of Radiology at Emory Hospital revealed elaborate mummification techniques, such as the presence of large amounts of resin (a highly valuable material) in the skull. The mummy was also subjected to radiocarbon dating, which placed it in New Kingdom times.

All this led specialists to affirm that the mummy in the Michael C. Carlos Museum was, with little doubt, that of Ramses I.

The Egyptian authorities, headed by Zahi Hawass, who at that time was Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt, did not take long to request the repatriation of the remains. The American institution did not put any objection.

Afterward, with all the fanfare that a pharaoh deserves, the mummy of Ramses I was placed in a simple wooden box covered with the Egyptian flag and returned to the Land of the Nile, where he was received with honors as head of state.

Since 2004, the mummy that belongs to the founder of one of the most important dynasties in Egypt rests forever in a special room in the Luxor Museum.

ٍSource: Carme Mayans, National Geographic