In the fifth year of his reign, Pharaoh Amenhotep IV and his beautiful wife Nefertiti, the Great Royal Wife, embarked on a lengthy journey from the country’s capital, Thebes, in Upper Egypt.

Aboard the royal barges, the monarch and his court traveled 225 kilometers down the River Nile until they arrived at Tell El-Amarna, also known as Amarna.

The Pharaoh interpreted his vision as a divine message: “It was my father, Aten, who instructed me to locate this place so that I could establish the Horizon of the Sun for him.”

Indeed, this appeared to be the site of a new city, founded by the King in honor of his new god, Aten, the solar disk, and he named it Akhetaten, the Horizon of Aten.

The royal entourage disembarked shortly after, and the so-called Little Temple began to take shape. Amenhotep documented the grandeur in the texts of the first monuments (stela) surrounding the chosen area.

The narrative crescendos with admiration for the god Aten and enthusiasm for the new capital, as the King designates the locations for the official buildings.

The Pharaoh went to great lengths to emphasize the role of his wife in the establishment of Amarna. In another text, he indirectly acknowledged that Nefertiti was his advisor and contributed to his decision-making.

Of further interest is another proclamation from the King: “I have made the ‘Horizon of the Sun’ as a farm for my father, Aten, and for it to endure in my name or in the name of the Great Royal Wife, Neferneferuaten Nefertiti.”

Akhenaten thus equates the enduring memory of his own legacy as the constructor of the Horizon of the Sun with that of the Queen.

Egypt Opens Its Capital

Amarna embarked on its journey as Egypt’s new capital.

From the onset of his reign, Amenhotep IV had aimed to establish the country’s primary god as the traditional universal creator, the Sun, under the patronage of Aten.

In Thebes, the traditional capital of the kingdom, the influential clergy of Amun and the haughty nobility of the time vehemently opposed this reform. This marked the end of statues and representations in human form of various deities, leaving only Aten.

To overcome this resistance, Amenhotep, now known as Akhenaten, opted to relocate the court to an uninhabited desert. The Pharaoh also chose to alter his own name, adopting Akhenaten, the “living spirit of Aten.”

Subsequently, the rulers, especially the Queen, assumed prominent roles in Amarna’s life.

Palace audiences, public processions, and religious celebrations punctuated the capital’s calendar, as depicted in the decorations of numerous tombs of Egyptian nobles preserved in the surrounding mountains.

The Royal Causeway, a grand processional route traversing the city from north to south, lined with temples and official buildings, held particular significance in these public events.

The sight of royal chariots passing along this avenue left the public in awe with unprecedented scenes. At times, the kings publicly exchanged kisses, while on other occasions, Nefertiti herself drove her own chariot – a sight rarely witnessed in other queens.

The Lady of Amarna

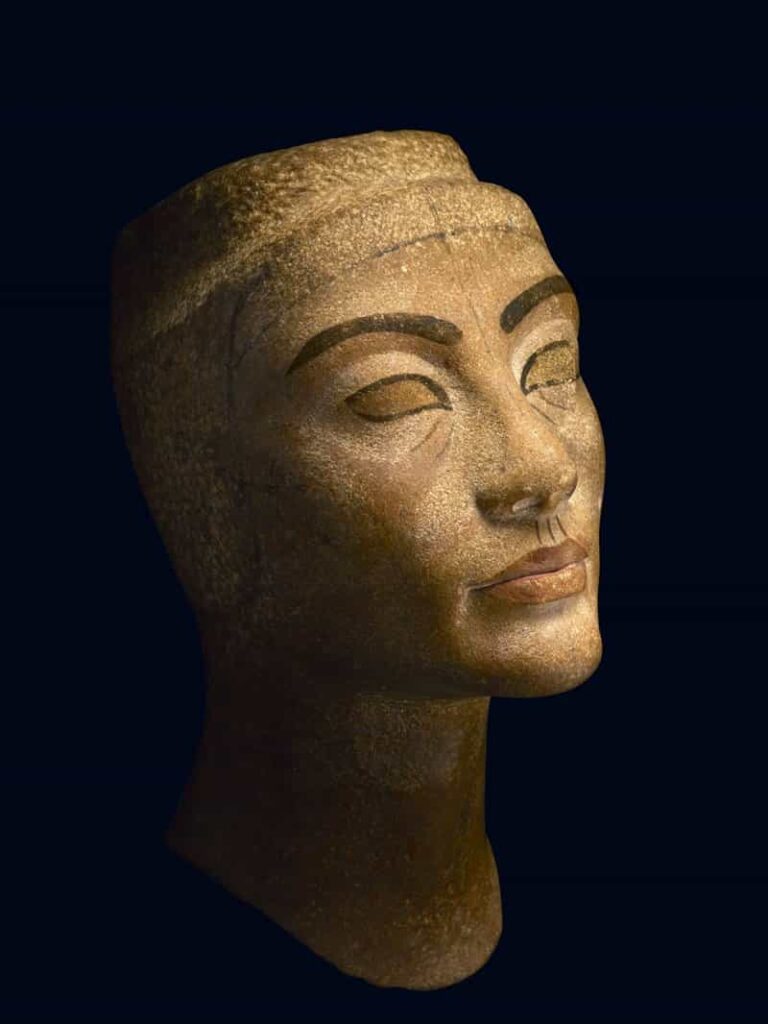

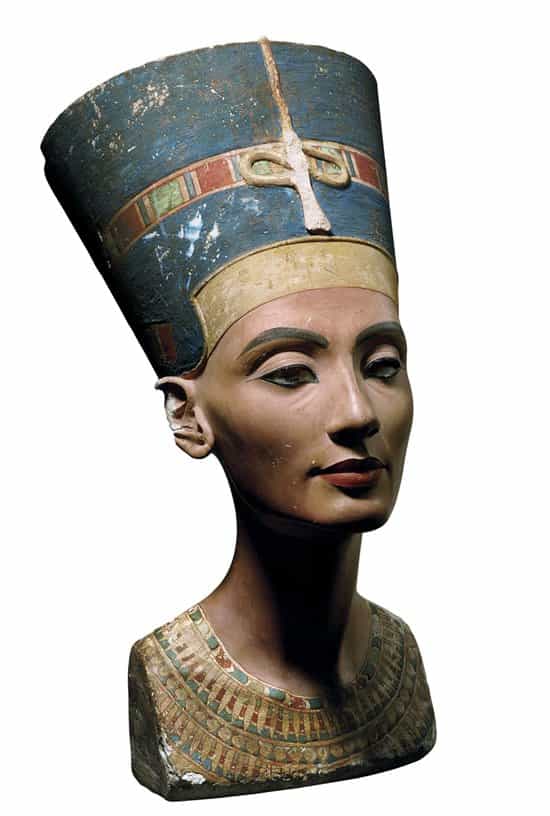

Nefertiti was adorned with titles that beautifully reflected the exceptional portrayal of her figure.

For instance, in the hieroglyphics adorning a column in the Great Palace, she is referred to as the ‘Lady of the Two Lands,’ without the need for the title of Great Royal Wife to precede it. This unique distinction makes her the only Egyptian queen to declare herself Lady of Egypt independently, without reliance on her husband’s title.

Conversely, in a relief from the cabin of the Queen’s ship, she assumes a pharaonic stance of crushing the head of a captive with a ritual mace, a scene typically associated with representations of Egyptian pharaohs.

Other depictions from Amarna offer a glimpse into the intimate family life of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, who openly expressed their affection for their daughters.

Stelae found in Cairo and Berlin that showcase these tender moments breathe new life into the otherwise formal pharaonic iconography.

The same sentiment is evident in the painting discovered by Flinders Petrie in the private chambers of the Amarna King’s House, believed to be the Pharaoh’s office. The delicacy and tranquility of the scene underscore the warmth of a family savoring their private moments.

From Glory to Oblivion

Despite the significant role of the Queen in Amarna’s history, she must have been aware of the challenges involved in establishing the new religious principles in the minds of her subjects in such a short span.

It’s noteworthy that in the case of Nefertiti’s two daughters, Neferure and Setepenre, the name of Aten was replaced with that of Ra. Could the Queen have sensed the unfavorable reception of the initiated changes?

To exacerbate matters, the international political situation took a turn for the worse in Egypt. Vassal princes were embroiled in conflicts, and the Hittite King, Suppiluliuma I, seized Egyptian colonies in Syria.

In the twelfth year of Akhenaten’s reign, a grand tribute festival was held, presumably to commemorate a victory over Nubia. We have detailed accounts of this event thanks to the solemn and vibrant depictions in the tombs of two noblemen, Huya and Meryre II, reflecting the distinctive style of Amarna art.

Shortly after this, King Akhenaten’s second daughter, Meketaten, passed away. She was interred in a chamber within the royal tomb of Amarna, where the grief of her parents and sisters is depicted. This is also one of the last instances where the Queen is mentioned in contemporary texts.

After the fourteenth year, Nefertiti’s whereabouts become unknown. It is possible that she passed away during the early years of Tutankhaten’s reign, at a time when he had already changed his name to Tutankhamun and abandoned Amarna, along with the Aten religion that Nefertiti and her husband had sought to promote.

Source: Theresa Armijo, National Geographic.

Amarna, the city of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Theresa Armijo. Alderaban, Cuenca, 2012.

Akhenaten. Dimitri Labory. The Sphere of Books, Madrid, 2012.