Under the last king of the New Kingdom, the influence of the priests of the god Amun was increasing, to the point that the high priest Herihor usurped royal authority and became the true power of Egypt.

The New Kingdom was the most glorious time of Egypt, turned into the greatest power in the Mediterranean. The dominions of the pharaohs stretched from the ports of Syria to the fiery sands of Nubia in present-day Sudan.

Egypt’s victorious armies had withstood the onslaught of two deadly enemies: the Mitanni and the Hittites. But success is not eternal.

Internal disputes and external threats undermined royal authority, as was evident in the time of Ramses III, the last great pharaoh of this period: the pharaoh rejected the violent attacks of the Peoples of the Sea, but died the victim of a conspiracy plotted in his own harem around the year 1153 BC.

Since then, Egypt has rolled downhill and the country was doomed to a decline with no possible recovery.

To the incessant internal struggles for power – led by the two dynastic branches that began after the reign of Ramses III (whose successors all bore this name) – must be added a series of insufficient harvests, which led to the impoverishment of the kingdom and even long periods of famine.

The decline of the authority and prestige of the pharaohs was manifested in the robberies of royal tombs, a plunder that had the character of true sacrilege, given the divine component of the Egyptian kings

Ramses XI ascended the throne in that atmosphere of increasing instability, towards the year 1099 BC. He was the last representative of the Twentieth Dynasty; when he died, the New Kingdom faded with him.

Who was Ramses XI?

In the opinion of the Egyptologist Jacques Pirenne, the last four Ramses were sons of Ramses VI and therefore brothers.

The last of them, our Ramses XI, is credited with twenty-seven years of reign. But his weakness and the strength of his adversaries made him a merely decorative figure during the last eight years of his tenure.

Herihor’s ambition

When Pharaoh’s authority wavered or disappeared in ancient Egypt, the emptiness it left was filled by the most powerful subjects.

In previous times of crisis (the first two intermediate periods) that authority was supplanted by the provincial governors or nomarchs and other local kings; now, at the end of the New Kingdom, it was to pass to the increasingly powerful clergy of the god Amun, centered in the great temple of Karnak, in the city of Thebes.

Towards the middle of the reign of Ramses XI, the power of the priests of Amun was increasing.

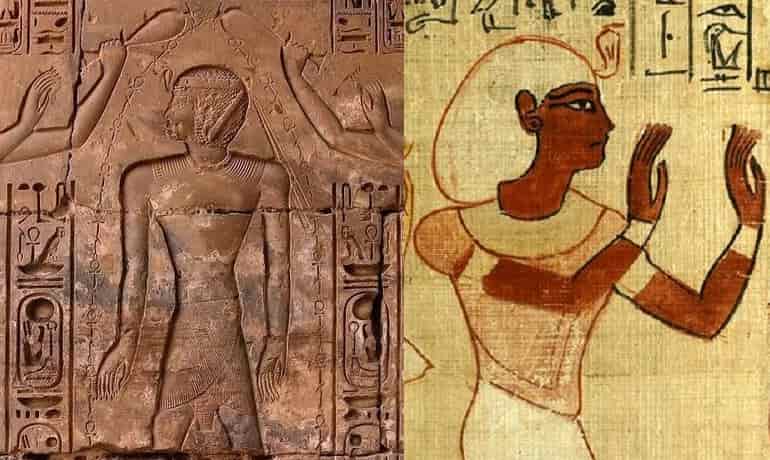

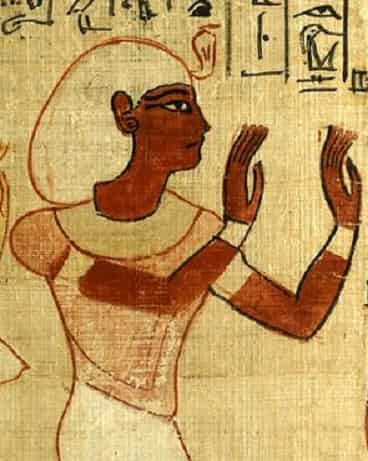

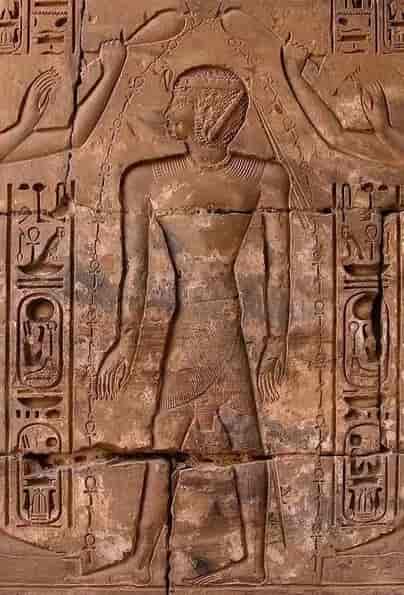

This increasingly powerful position was recorded by the high priest of Amun-Re, Amenhotep, who had his image carved equal in size to that of Ramses XI on the walls of Karnak.

His audacity should not have been limited to this, since shortly after he was removed from his position, not without creating a serious internal conflict in which the viceroy of Nubia, Pinehesy, intervened.

The office of high priest of Amun-Re was vacant for at least nine months, something that had not happened since the turbulent time of Akhenaten, the heretical pharaoh.

The era of the renaissance

After the time of Amenhotep as high priest, the highest religious hierarchy passed into the hands of Herihor who, apparently, was of Libyan origin and came from the army.

The political influence that he displayed from his office soon changed the history of Egypt, because Herihor realized the threat that four hundred years ago had motivated the revolution of Akhenaten: that the power of the clergy of Amun would surpass that of the Crown.

To escape this danger, Akhenaten proclaimed Aten, the solar disk, as the sole divinity of Egypt, of which he himself became supreme pontiff, and built a new capital, Amarna, far from Thebes and the clergy of Amun.

Did Ramses fail to assess the danger Herihor posed to his own authority?

In fact, with the appointment of Herihor as high priest of Amun-Re, the pharaoh had tried to counteract the power of the clergy by putting as superior a man who enjoyed his full confidence.

With the same intention, he appointed Herihor general in chief of the army of Upper Egypt and Nubia, thus protecting himself from a possible insurrection by Pinehesy, the viceroy of Nubia.

Ramses would close the southern defensive circle by appointing Herihor viceroy of Nubia. As might be expected, the performance of Ramses provoked the wrath of Pinehesy, who soon dissociated himself from Egypt, retaining command of the Nubian army.

This meant the final loss of the empire created almost five centuries earlier by Thutmose III, the conqueror of Nubia and Asia.

Ancient Egypt was thus returning to its old borders: the Mediterranean to the north, and Aswan to the south, at the height of the first cataract of the Nile.

The decisions of Ramses had been turned against him. Not only had Nubia lost, but Herihor actually assumed pharaonic power.

In the year 19 of the reign of Ramses XI, the same year in which he was appointed viceroy of Nubia, Herihor took a definitive step: starting a new era from scratch, which he christened “whm-mswt”, “the era of the Renaissance.”

Traditionally this was the case when a pharaoh ascended to the throne, marking the chronological beginning of his reign.

Now, the “official” king was still Ramses, but the command was exercised by Herihor, who soon inscribed their names on individual cartridges, a royal prerogative that he also usurped.

Egypt, split in two

Herihor’s ascension to supreme power is evident in the sanctuary of the god Khonsu (revered as the son of Amun), located in the sacred precinct of Karnak and which was completed in those years.

In a first phase of the decoration of this sanctuary, Herihor and Ramses XI appear at the same level, making offerings to the divinity; but then it is Herihor who claims the construction of the temple, relegating the king to the background, before totally ignoring him in the last dedicatory inscriptions.

In this convoluted matter there is a third character in contention: Smendes, who administered Lower Egypt (the region of the Nile delta) from the city of Pi-Ramesses.

Smendes, who also came from the clergy of Amun, built a new city in the eastern delta: Tanis, about 25 kilometers north of Pi-Ramesses. This last city was completely dismantled to build the new capital with its materials.

It is likely that such a sudden transfer was due to a change in the hydrography of the Delta: the branch of the Nile that supplied Pi-Ramesses with water and was its route of transport changed its course and moved away from the city.

In any case, the new location must have been decided taking into account the important port that opened on the arm of the Nile where Tanis was built.

It was an essential outlet for increasingly heavy commercial maritime traffic, and a basic defensive post in the region.

Egypt lived in an unstable political balance. In Lower Egypt Smendes ruled together with his influential wife Tentamun, daughter of Ramses XI.

In Upper Egypt, Herihor, which brought together the religious, executive and military powers; and in Nubia, Pinehesy.

Although Ramses XI was the legitimate king, his role was reduced. But Herihor’s ambition was only partially fulfilled: he tried to crown himself on the death of Ramses XI, but fate would have him perish around 1074 BC, before the king.

Despite this, he materialized the dream long cherished by the clergy of Amun: to create a religious dynasty that would displace the Theban monarchy.

The government of Thebes was continued by Piankhi, who succeeded his father Herihor as High Priest of Amun.

For his part, Smendes, married to a daughter of Ramses XI, used this kinship to justify his proclamation as pharaoh, becoming the founder of the Twenty-first Dynasty.

As for the pharaoh, we do not know anything about the circumstances of his death, which occurred around 1069 BC, nor do we know if he was buried in the tomb KV4 of the Valley of the Kings, prepared for him, but which remained unfinished despite the long reign of its owner.

Thus ended the New Kingdom and began the Third Intermediate Period.: with the country of the Nile divided between a Lower Egypt ruled by the pharaohs of Tanis and an Upper Egypt ruled from Thebes by the high priests of Amun.

Around 1070 BC, in Thebes, Pinedjem I succeeded his father Piankhi at the head of the priests of Amun and the army of Upper Egypt, although after his marriage to Henuttawy, another daughter of Ramses XI, he resigned his religious position and adopted the Pharaonic titles.

Source: National Geographic.

History of ancient Egypt. Nicolas Grimal, 2011.