Seqenenre Tao was the pharaoh who ruled southern Egypt during the late 17th dynasty, approximately between 1558 and 1553 BC.

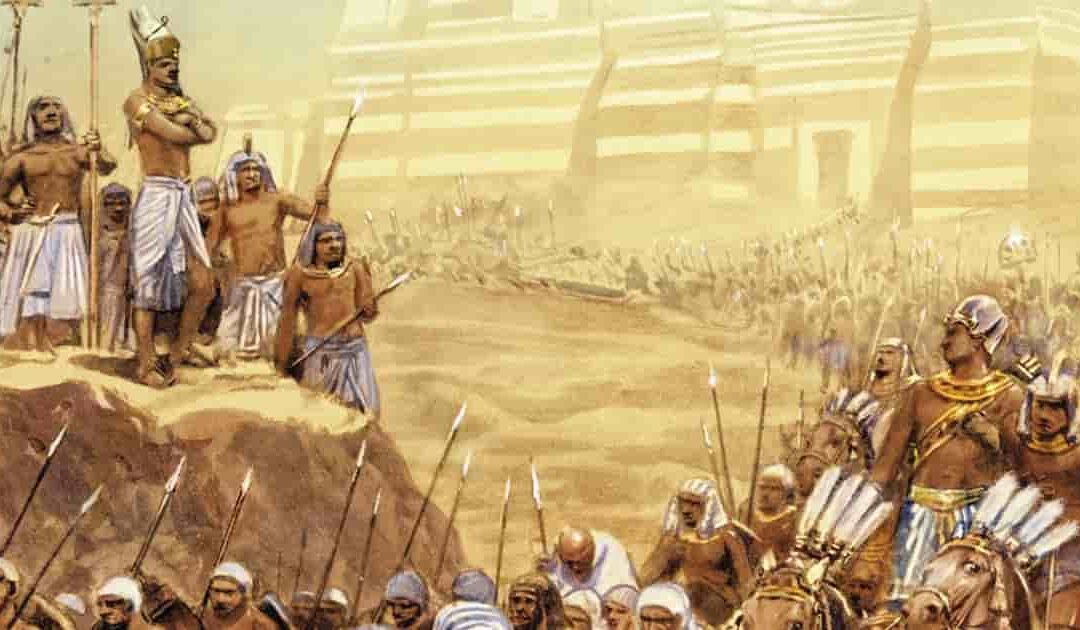

It was a troubled era. The Hyksos, known in ancient Egyptian as Heqau-khasut, “the rulers of foreign lands,” held control over the northern part of Egypt and established Avaris (present-day Tell el Dabaa) as their capital during the “second intermediate period” (1650 -1550 BC).

Despite the pharaohs retaining power in the south, with their capital in Thebes, the entire region was compelled to pay tribute to the invaders.

An ancient papyrus revealed the hostilities between Seqenenre and the Hyksos King named Apepi or Apophis.

As per the text, Apophis sent a hostile message claiming that noisy hippos in a pond in Thebes disturbed his sleep in Avaris (400 miles away), and demanded the destruction of Theban sacred space.

While the conclusion of the story is lost, the document ends with Seqenenre summoning his advisors, perhaps to initiate hostilities.

Deir el-Ballas, a settlement north of Thebes established during this pharaoh’s reign, likely served as the base for military campaigns against the Hyksos.

Throughout the conflict, Seqenenre’s eldest son, named Kamose, perished in battle, leaving his brother Ahmose to complete the expulsion of the Hyksos. Ahmose pursued them to Sharuhen (located in the present-day Gaza Strip) to reunify ancient Egypt.

However, the fate of Seqenenre remains a mystery, as his presence abruptly vanishes from the narrative.

In 1881, archaeologists discovered his mummy in Deir el-Bahari (Thebes). The inscriptions on the original linen wrappers confirmed that this was the body of Seqenenre-Tao.

Tao (or Taa) represented his birth name, signifying “Thoth is great,” while “Seqenenre” was the throne name, translating to “He whom Ra has made brave.”

In the 19th century, researchers observed the deteriorated condition of the body, indicating limited mummification, and noticed severe head injuries, suggesting a violent death.

However, there were no injuries found elsewhere on the body. Over the years, various theories emerged. Did he perish in battle? Was he a victim of a palace conspiracy? Why was his mummification hastily conducted?

It took more than a century to uncover answers to these questions. A recent CT scan has unveiled previously unknown details of his injuries, cleverly concealed by embalmers, according to specialists in an article published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

X-rays confirmed that Seqenenre was captured on the battlefield, as his hands displayed evidence of being bound behind his back, hindering any chance of escape or defense against an attack.

“This implies that the pharaoh was at the forefront alongside his soldiers, risking his life in the fight to liberate Egypt,” stated Dr. Sahar Saleem, a Cairo University professor of radiology.

The analyses conducted suggest that the execution was carried out by multiple assailants. The examinations found traces of up to five different weapons from the Hyksos that matched the wounds of the Egyptian king. “Seqenenre’s demise was more of a ceremonial execution,” she explained.

“In a typical execution of a restrained prisoner, it could be assumed that only one assailant would attack, possibly from different angles but not with different weapons,” Saleem clarified, who collaborated on this case with former Egyptian antiquities minister and archaeologist Zahi Hawass.

Seqenenre was in his 40s when he died, and his embalmers took great care to conceal his injuries.

They utilized a sophisticated technique to cover the head injuries under a layer of embalming material that functioned akin to fillers used in contemporary plastic surgery.

This suggests that the mummification occurred in a specialized mummification laboratory rather than a poorly equipped setting, as previously thought.

Saleem and Hawass were pioneers in utilizing CT scans to study pharaohs and warriors of the New Kingdom.

“Seqenenre was at the forefront of the battlefield. His demise inspired his successors to continue the struggle to unify Egypt and initiate the New Kingdom,” they concluded.