Papyrus boats, rowing and transport ships, sacred boats… during the Pharaonic era, various boats sailed the Nile and even the high seas.

Without the Nile, the holy river, Egypt would only be a vast desert. In ancient times, the annual rise of its waters guaranteed the sustenance of those who lived on its shores and, at the same time, served as a privileged communication route along the thousands of kilometers of its channel.

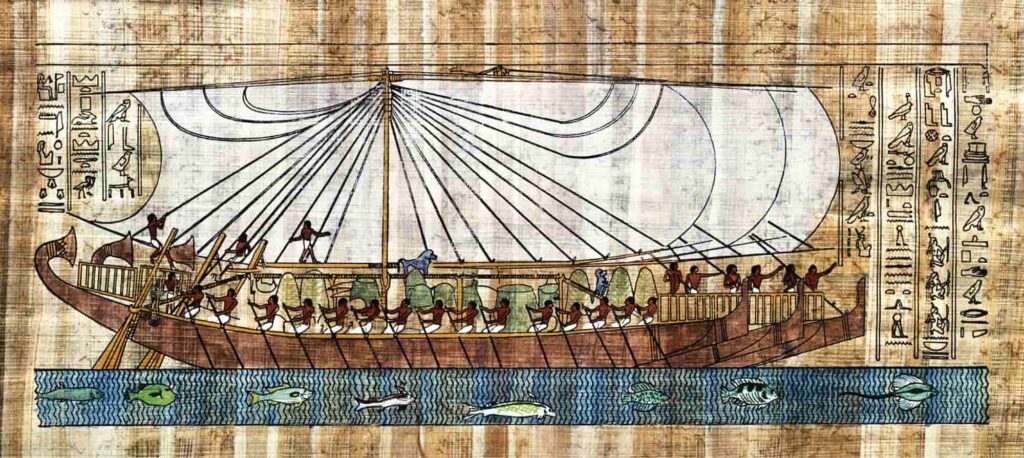

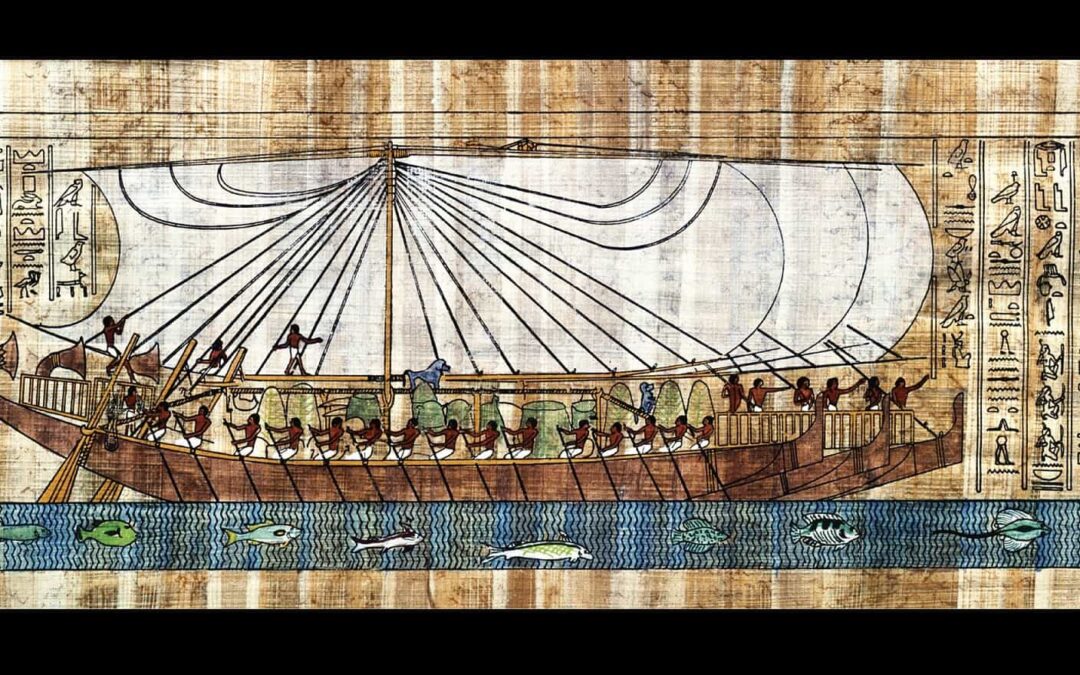

For this reason, in the daily life of the ancient Egyptians, ships played a fundamental role, whether it was for the movement of people, the transport of goods, or numerous religious ceremonies.

Due to its scarcity, very few remains of these vessels are preserved, probably because the wood they were made from was a precious commodity. Without a doubt, it was often reused to make coffins, but there are numerous representations that show us the different types of ships and their evolution.

Thus, some vases of the predynastic period show that rowing boats with double cabins abounded then, and the hull followed a uniform curve from bow to stern.

This characteristic of the great Egyptian ships served to differentiate them from other supposedly Asian ones.

In a tomb at Hierakonpolis, whose painted remains are preserved in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, we see five white-hulled ships with the typical Egyptian curved line, but a sixth ship, with a black hull, has an almost vertical stern.

The Louvre Museum exhibits the Gebel El-Arak knife from the predynastic period, whose ivory handle depicts a naval battle.

Some of the ships maintain the classic Egyptian typology, but others have both the stern and the bow raised, and one of the cabins is convex, like that of the black boat in the tomb of Hierakonpolis.

While some authors see a military confrontation in the scene between ancient Egyptians and Asians, others interpret a fight between Egyptians: an army from Upper Egypt against a coalition from the Delta.

In addition to these first large ships, the Nile welcomed very different types of vessels. Both fishermen and farmers moved in small skiffs made of papyrus.

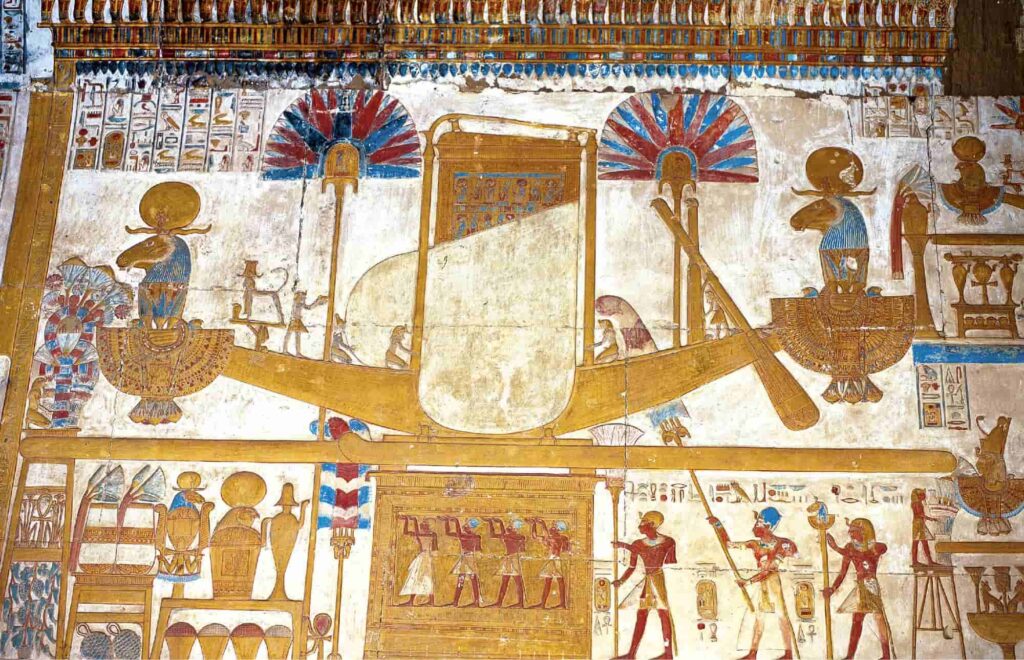

And not only men: Ra, the King of the gods, traveled in one boat during the day and made the gloomy voyage of the night in another.

Although, as we said, there is hardly any material trace of these ships, archaeologists have made some remarkable finds. In 1991, an American mission discovered fourteen tamarisk-wooden boats in the necropolis of Umm El-Qaab in Abydos, where the kings of the first two dynasties were buried.

The boats, twenty-three meters long, were found lined up, buried at a shallow depth, protected on the sides by adobe walls, and covered with a paste of silt and lime.

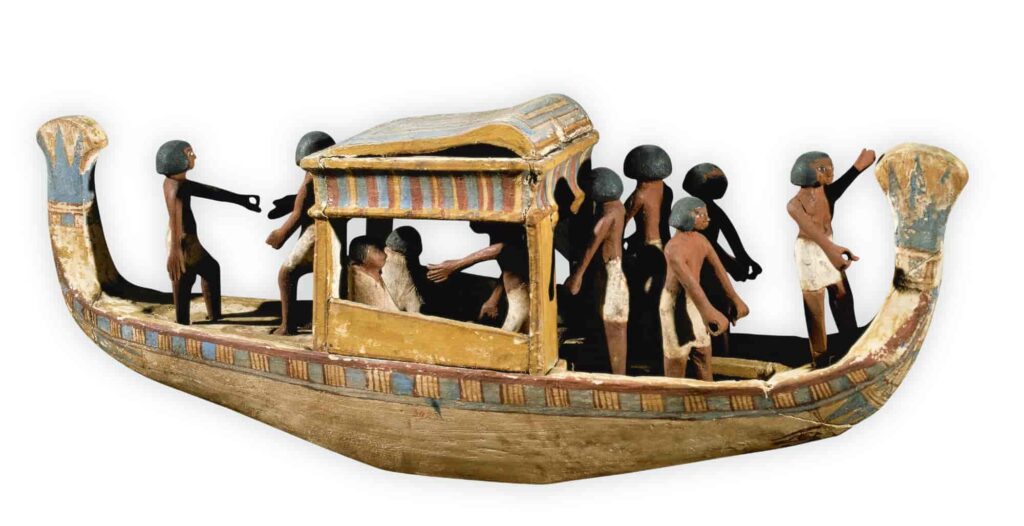

In general, boats were part of the grave goods of kings and high dignitaries, as evidenced by the numerous boat-shaped graves found next to the mastabas and pyramids of the Old and Middle Kingdoms.

Pits that once housed boats that did not have to be “solar”, with an exclusively funerary purpose, as has been written, could have sailed down the Nile.

After the discovery of Abydos, it is necessary to go back to the fourth dynasty to find boats destined for the funerary trousseau of another pharaoh, Khufu.

One of them, found in 1954, is now exhibited in the Grand Egyptian Museum. This ship navigated the river because, among other signs, its boarding plan shows signs of use.

In the Khufu ship, the different boards of the hull were interlocked with esparto ropes, while in those of Abydos, the traditional system of boxes and tenons, commonly used in carpentry, was used.

What archeology says

The third major ship find was in Dashur, about forty kilometers south of Cairo. In 1894, next to the pyramid of Senusret III, Jacques de Morgan discovered six cedarwood boats from the twelfth dynasty, four of which are still preserved today.

One is in the Chicago Museum, another in the Pittsburgh Museum, and the other two in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Their length varies from 9.4 meters in Pittsburgh to 10.2 meters in one in Cairo. Two long oars at the stern served as a rudder.

During the Middle Kingdom, technical improvements were made to ships. A single oar was placed aft and used as a rudder instead of the two in common use in the Old Kingdom, and the double mast also disappeared and was replaced by a single mast. Despite this, the hull design of the ships remained basically the same.

We can learn in detail what the ancient Egyptian ships were like by the decoration of the tombs, which usually included bas-reliefs or paintings of ships with more or less defined details.

In the mastabas of Ptahhotep and Ty, from the fifth dynasty, we witness the construction of wooden and papyrus boats in Saqqara.

Other details of rigging, sails, ropes, and the cabins of transport and pleasure boats can be seen on the western wall of the pillar room of the mastaba of Mereruka, vizier of Pharaoh Teti, from the sixth dynasty.

Here, too, it can be seen that the ships had only one mast and a square sail. The mast, at this time, was made up of two sticks that were joined at the top. There, a fixed semi-circular piece allowed the sail hoist ropes to slide.

On the causeway of Unas, the last pharaoh of the fifth dynasty, there are boats engraved on the wall. The scene details how a system of thick hemp ropes allows the great mast to be lowered onto the deck, on which rest two columns are destined for the King’s funerary temple.

These large columns, one in the temple below it and another in the Louvre Museum, give an idea of the great weight that the boat could support.

Source:

National Geographic.

The priests in ancient Egypt. Elizabeth Castel. Alderabán, Madrid, 1998.

Texts for the ancient history of Egypt. JM Serrano Delgado. Chair, Madrid, 1993.