The art of writing and mastery of the written word were crucial in the development of the Pharaoh’s civilization. The written heritage is vast and encompasses many genres, used for both temporary and eternal purposes.

Writing was initially used for economic purposes but quickly gained a greater significance: “Be skilled with words […]. Words are worth more than all the combats,” King Merikare of the Tenth Dynasty is exhorted in teachings written by his father.

In ancient Egyptian society, scribes were essential for the construction of the economic and cultural framework. Firstly, they created writing for daily use, as it was necessary to record every action that took place in the Nile valley methodically and exhaustively.

Secondly, they refined the language to capture abstract concepts and religious beliefs. Ready to listen and write, this official represented obedience and loyalty to the state that had elevated them. The ancient Egyptians held this profession in high regard.

Many texts suggest that this profession offered the best future. The most famous is the Satire of Trades, composed during the 12th Dynasty.

However, we do not know much about the reality of the educational system in ancient Egypt. It appears that access was limited to a select few, with the goal being to educate future civil servants who would work in the administration or join the ranks of the priesthood or army. In general, a person’s professional career followed that of their parents.

Aware of their group identity, the training of scribes was essential. To become a “skillful finger scribe,” they had access to numerous schools. Most of these schools offered elementary instruction (reading, writing, and calculating), which could be accessed at age 10.

Higher studies (such as astronomy, medicine, geometry, or architecture) were taught in temples, which were important economic and cultural entities.

In 2002, a French team discovered the remains of a school for the first time. It was found in the Ramesseum, a temple built by Ramses II in western Thebes, and it was held outdoors, like most schools seem to have been.

The Kap, a prestigious school reserved for princes and the children of the elite, located inside the royal palace, deserves special mention.

The relationship between students and teachers was based on respect and obedience. Reliefs show boys sitting on the ground, attentively listening to their lessons with their backs curved. Some even had brushes behind their ears, ready to be used for writing.

While the greatest virtue of a good student was to listen, patience was also important. Before a student could become a scribe, they had the difficult task of learning to draw the hundreds of written signs and their phonetic values.

Students first learned cursive, a quick and simplified version used to write with brush and ink on papyrus. Hieroglyphic writing was at a higher level due to its sacred and monumental nature. Carved into stone, the text became an integral part of the decoration. At this point, the scribe’s role merged with that of the artist.

The methodology for learning involved memorization and recitation. To aid in their studies, students had manuals with sample letters, formulas, and basic texts. They also memorized long lists of words organized by class for an encyclopedic purpose.

In addition to reading, apprentice scribes were responsible for systematically copying texts of moral significance. This not only taught them the proper techniques for being a scribe, but also instilled in them the values of ancient Egyptian society. In particular, a type of wisdom literature called “teachings” or “instructions,” written by a father to his son, was widely popular.

The most famous of these texts is the Satire of Trades, in which Khety talks to his son Pepy on the way to school, encouraging him to be diligent and highlighting the advantages of being a scribe.

Students in ancient Egypt were not much different from students today. Since papyrus was expensive, they used cheaper materials like wood, pottery, and limestone (called ostraca) for writing texts, noting formulas, or practicing calligraphy.

These materials were often written on both sides and, on occasion, wooden boards were covered with a waterproof stucco to allow for reuse.

Students used black ink for the texts and reserved red ink for titles, chapter beginnings, and teacher corrections. It was also common, as it is today, to indicate the date of dictation in red.

The constant copying of texts, whether partial or complete, often led to deformations, resulting in multiple versions of the same text. Sometimes, the reconstruction of a document is only possible thanks to the chance discovery of pieces copied on different dates and found in different locations in Egypt.

However, it is a paradox of history that many of these drafts are the only surviving copies of great works of Egyptian literature, such as the famous Story of Sinuhé, which became a classic in ancient Egyptian school programs.

The quality of these writing exercises reveals which students were more advantaged, with good handwriting and free of spelling errors.

At the service of the state

The abundance of texts glorifying the role of the scribe is not coincidental. In reality, they are the result of a well-planned propaganda campaign by the state to showcase its effectiveness.

Since around 3000 BCE, ancient Egypt was organized as a unified country under a monarchy, and the scribe played an active role in the development of the new administration. This was especially true from the Middle Kingdom, the period during which the Satire of Trades was composed.

During this process, writing and language became crucial tools for imposing centralization against local dialects. The high level of bureaucratization led to the inclusion of scribes in all sectors and strata of society.

They became almost ubiquitous, appearing in the civil and military administration, the palace, and the temple. In return, they were required to have a high level of specialization, which led to an increase in the number of titles: scribe of the barns, scribe of the archive, scribe of the pasture of the cow herds, etc.

Scribes recorded tax collection, calculated crops, accompanied soldiers on expeditions, and provided services to individuals by writing letters, wills, and reading correspondence.

Every property owner needed a scribe to manage their affairs. This bureaucracy was accompanied by an accumulation of “paperwork,” with all documentation kept in archives for consultation.

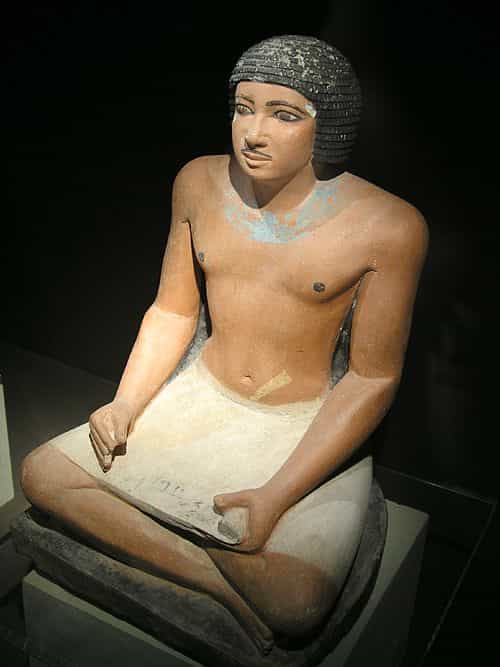

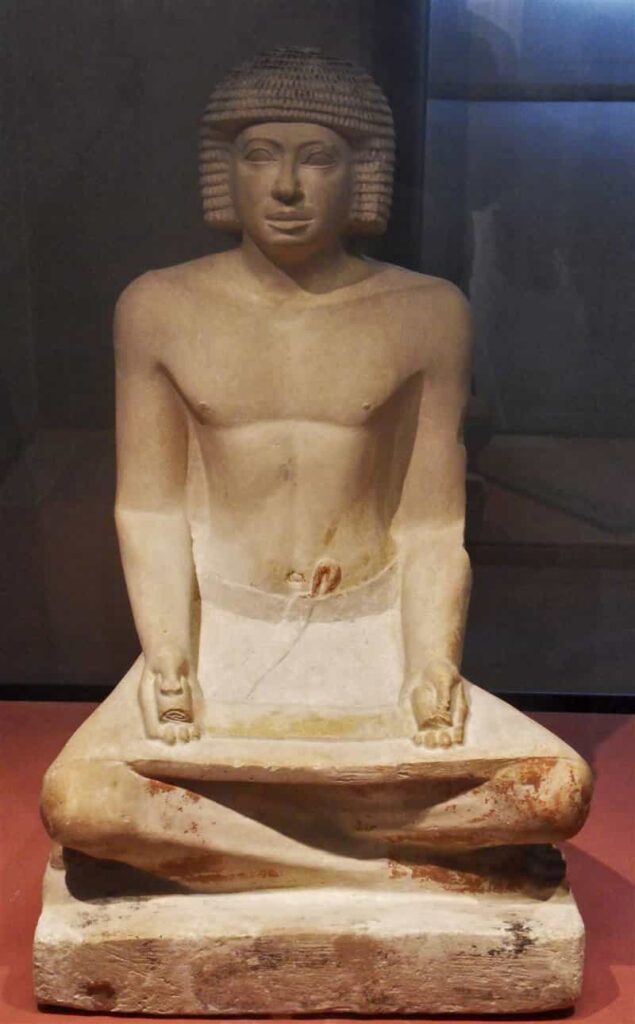

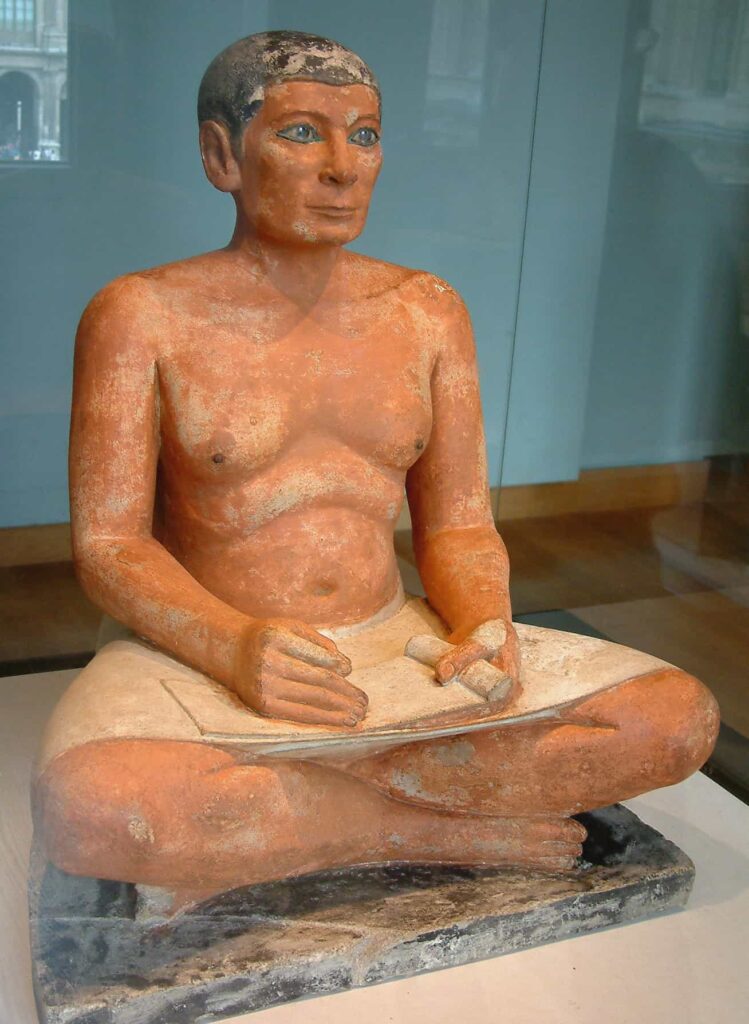

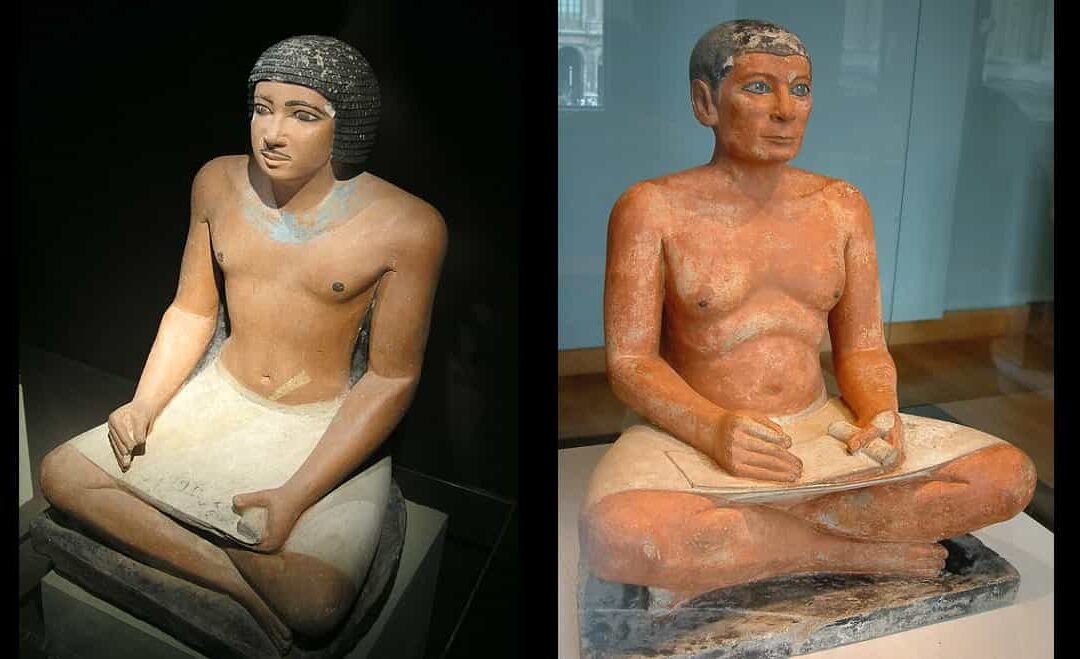

As allies of the Pharaoh, scribes were rewarded with upward career mobility. The famous statues of seated scribes with a papyrus scroll on their knees reflect their social status and class pride.

They were organized into a hierarchy of directors, with the vizier, the Pharaoh’s right-hand man, at the top. Promotions seem to have been relatively easy to attain.

Under the auspices of Thoth

Hieroglyph is a Greek term. The ancient Egyptians referred to their hieroglyphic writing as “words of the god.” According to ancient Egyptian mythology, the god Thoth received writing from the hands of Ra and was tasked with teaching it to humans.

Thoth served as the scribe of the gods, recording all divine acts in writing. He was responsible for writing the name of the new Pharaoh on the leaves of the divine tree and recording the verdict in the trial where the heart of the deceased was weighed to determine their eligibility for eternity.

As a result, Thoth, depicted as a baboon or ibis, became the patron of the guild of scribes. His main cult center was in the city of Khmunu, known as Hermopolis by the Greeks, who equated Thoth with their god Hermes.

Upon mastering writing, scribes took on the task of composition. In prestigious temple schools known as Houses of Life, copyists responsible for reproducing sacred texts were trained. These schools were also research centers for religious and scientific study, where experts could consult works.

The country that invented papyrus had a deep reverence for the book. According to a well-known document, a book was more useful than building a house or tomb and was worth more than establishing a residence. The goddess Seshat, Thoth’s wife, was the protector of the “archive of the divine scrolls,” where religious books were kept.

Source: CRISTINA GIL PANEQUE, historia y vida