Ouroboros, the symbol of eternal cycles, finds its earliest graphic examples in the art of Pharaonic Egypt.

In its simplest representation, the ouroboros features a snake biting its own tail, forming a circle—a metaphor for the perpetual cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

The choice of a snake as the predominant animal in these depictions is no coincidence, as these reptiles shed their skin, symbolizing a form of rebirth.

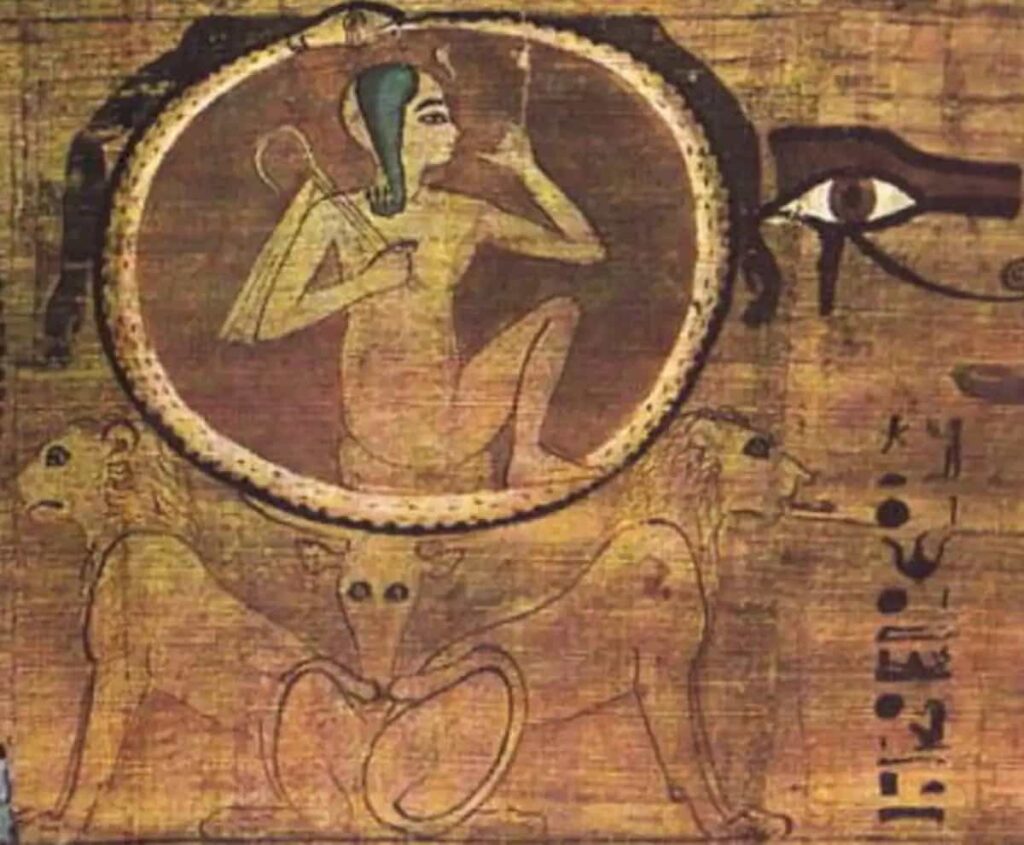

In ancient Egypt, the ouroboros is frequently depicted in association with the solar disk, reflecting the cyclical nature of daily death and resurrection, much like the sun.

The oldest documented representation of the Egyptian ouroboros was uncovered in what is perhaps one of the most renowned archaeological discoveries of all time: the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Specifically, it was found within the hieroglyphs adorning the walls of the second chapel, featuring texts from the Book of the Dead, which refer to the union of Ra and Osiris in the Duat (Underworld).

The ouroboros is depicted twice: once encircling the head and torso of a large figure believed to represent Ra-Osiris as a unified character (with Osiris being reborn as Ra), and again wrapped around the figure’s feet below the knees.

These two snakes, which naturally bite their tails, represent the deity Mehen, known as “the one who coils.” Mehen takes on the form of a serpent but is regarded as benevolent and serves as the protector of the Solar Boat of Ra during its nightly journey through the Duat.

Because of this role, Mehen is often depicted enveloping the boat, acting as a shield against Apophis, another serpent symbolizing the forces of evil and universal chaos.

The ancient Egyptians continued to incorporate the ouroboros into their iconography, leading to its appearance in various contexts. It can be found in reliefs and paintings adorning the temples of Abydos, Dendera, Kom Ombo, Edfu, and Karnak, as well as on the stele of Ra-Horakhty and within the tomb of Hatshepsut. Additionally, it appears in various papyri from the era.

The Greeks and Romans, recognizing the significance of this symbol, incorporated it into talismans and amulets. Even classical authors like Servius the Grammarian, in the 4th century AD, interpreted the pharaonic ouroboros as representing the annual agrarian cycles.