The mummy of the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep I (who reigned between 1525 and 1504 BC) was buried twice. The first, when he died. The second, in the Twenty-first Dynasty (from 1070 to 945 BC), when the priests buried him in Deir el-Bahari.

From that moment, 3,000 years ago, the pharaoh rested in peace. At least until 1881, when the adventurers of the time found his grave.

The mummy was still completely covered. And it remained that way for more than a century.

All royal mummies found in the 19th and 20th centuries have been opened for study, and Amenhotep’s was an exception. No one dared to break the charm of its perfectly preserved packaging, its beautiful decoration with flower garlands or the exquisite realistic mask that covered its neck and face.

In order to unravel the secrets it still hides, the legendary archaeologist Zahi Hawass and radiologist Sahar N. Saleem, from the Cairo University School of Medicine, have studied the remains using non-invasive methods to discover details about the physical appearance, the health and cause of death of Amenhotep I.

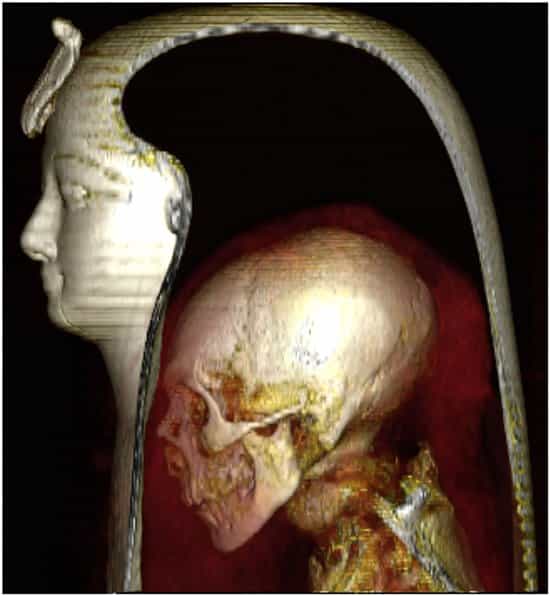

A computerized tomography (CT) scan allowed us to see the face of the pharaoh, who died around the age of 35.

“He was approximately 169 cm tall, circumcised, and his teeth had minimal wear,” write the specialists in a study published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine. “And they removed the viscera from his body through a vertical incision in the left flank,” they add.

“The heart is seen in the left hemithorax with a superimposed amulet, the brain was not removed and the mummy has 30 amulets or pieces of jewelry, including a band of metal beads (probably gold)”, they point out after their analysis, which included front and side three-dimensional CT images.

The mummified body of Amenhotep I suffered multiple post-mortem injuries and, according to Egyptologists, they were likely inflicted by grave robbers. Hawass and Saleem also believe that the embalmers of the 21st Dynasty tried to correct the damage.

This included wearing a resin-treated linen band to fix the detached head and neck from the body, covering a defect in the anterior abdominal wall with a band and placing two charms underneath, and placing the detached left upper limb next to the body and wrapping it around..

“The right forearm is individually wrapped, probably representing the original 18th Dynasty mummification,” they write.

The head mask is made of cardboard and has stone inlays for the eyes. “By digitally unwrapping the mummy and ‘peeling off’ its virtual layers – the mask, bandages, and the mummy itself – we were able to study this well-preserved pharaoh in unprecedented detail,” says Sahar Saleem.

“Amenhotep I probably bore a strong physical resemblance to his father Ahmose I: He had a narrow chin, a small, narrow nose, curly hair and slightly protruding upper teeth,” she adds.

If Ahmose I was able to expel the Hyksos and reunify Egypt, his son Amenhotep lived a golden age in a prosperous and safe country. Upon his death, he was worshiped as a god.