It is not new to say that the ancient Egyptians did everything possible to achieve eternal life after their death. To accomplish this, they meticulously prepared their tomb, known as the house of eternity, and also preserved their body as a mummy to ensure its everlasting existence and protect it from decay. The body was regarded as absolutely essential for ensuring survival in the afterlife.

According to the ancient Egyptians, humans consisted of certain spiritual elements in addition to the physical body (Khat). These elements, together with the body, were vital for attaining eternity. There were five of these elements: ren (name), Shuyet (shadow), ka (double or life force), ba (personality or soul), and akh (spirit).

The Importance of Having a Name

The name, or Ren, was one of the most crucial aspects of a human being as it provided identity. Without a name, one was reduced to the status of a “non-person,” effectively ceasing to exist. This was considered the worst fate imaginable for an ancient Egyptian.

For this reason, the name of the deceased was inscribed in numerous places within the tomb, such as doors, walls, and objects. It was even expected that anyone passing by the tomb would pronounce the name of the person buried there aloud, ensuring their continued existence in the afterlife.

This concept remained virtually unchanged throughout Egypt’s history. Even during the Greco-Roman period, all deceased individuals, including those buried in mass graves, were marked with a card displaying the name and title of the deceased to guarantee their afterlife. The fear of permanent death resulting from the loss of identity was a constant concern among ancient Egyptians of all eras.

The Shadow and the Ka

The shadow (Shuyet) is described in funerary texts as a potent and swift entity. Additionally, the shadow was associated with the Sun and connected to the concept of rebirth.

In fact, it was the Sun that cast the shadow of a person, creating an image of the individual. When the Sun set in the west, the shadow momentarily disappeared only to be reborn the next day with the rising sun. It was believed that the Sun assisted the deceased by ensuring their existence continued in the afterlife.

Regarding the Ka, this is a concept that Egyptologists have yet to fully comprehend. What is clear is that it came into being at the same time as a person and accompanied them throughout their life, like a double, until their death. It was the life force that animated them and needed to be preserved after death.

To achieve this, one of the most important components of grave goods were the so-called “Ka statues” in which the Ka was represented, alongside the mummy. Some of these statues depicted the hieroglyphic symbol of the Ka on their heads: two raised arms signifying protection or praise.

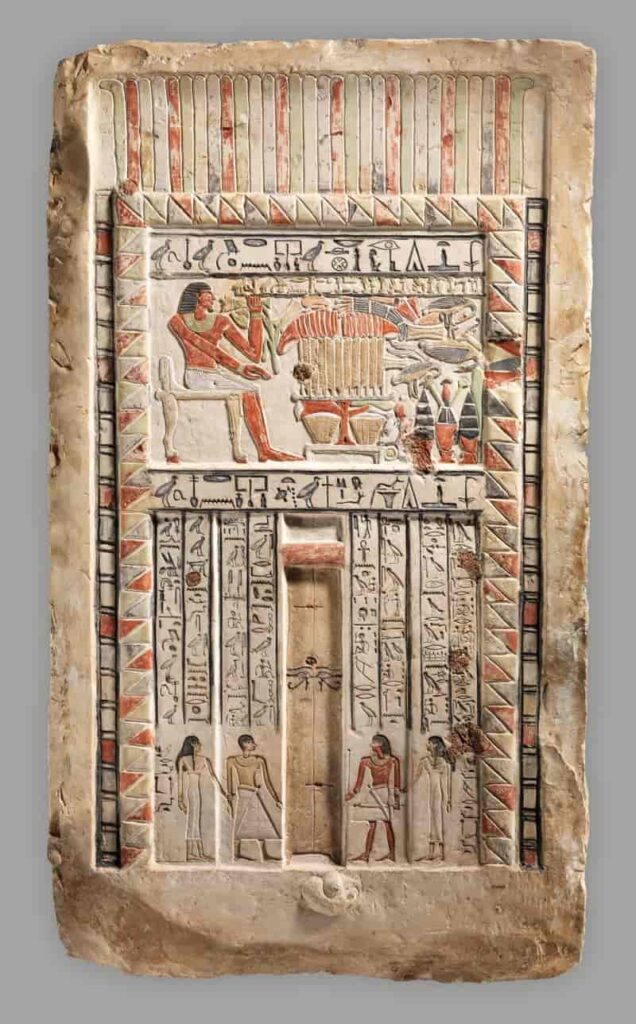

Funerary texts inform us that the Ka continued to exist after death, but it required sustenance to do so. The food offerings placed in the tomb served this purpose. Of course, the Ka did not physically consume the food, but rather absorbed its essence, gaining the energy necessary for its eternal life.

The Ba Takes Flight

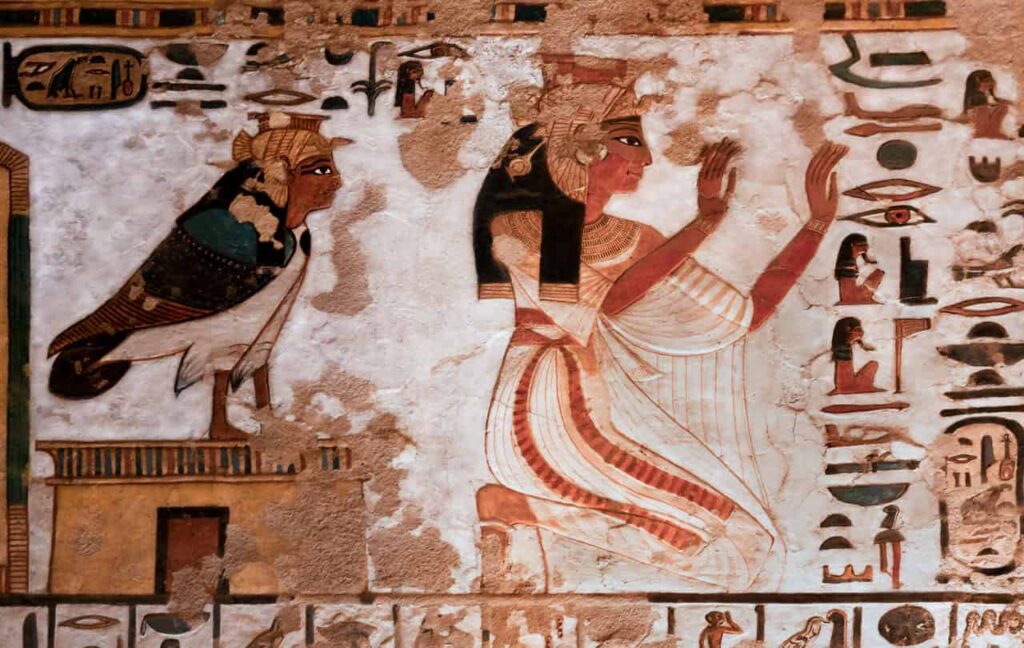

Another significant element that constituted the spiritual aspect of an individual was the ba, depicted as a bird with a human head (sometimes with arms). This spirit possessed wings that allowed it to move from within the tomb to the outside, making it the most agile spiritual component. Moreover, the ba possessed human-like capabilities: it could eat, drink, speak, and, as previously mentioned, move.

But why was it portrayed in the form of a bird? This avian form provided the individual’s spiritual aspect with enhanced mobility and also connected it to migratory birds. Despite its ability to move freely, the ba had to return to the mummy every day, as failing to do so would result in the deceased’s inability to survive in the afterlife.

The depictions of the ba began to gain prominence, particularly during the Middle Kingdom (1980-1760 BC), and reached their peak during the New Kingdom (1539-1077 BC). During this period, they became a common feature in tombs, a tradition that persisted until the end of the Roman era.

A Being of Eternity

Finally, the akh is perhaps one of the most complex concepts. Experts do not agree on the exact nature of this characteristic of the human personality.

One theory suggests that the akh was the union of the ka and the ba, wherein the deceased transformed into an eternal and unchanging being. However, it appears that not everyone could become an akh. Only those who had led a life in accordance with maat (order, harmony, and justice) were capable of doing so.

The akh was symbolized by the hieroglyph of the hermit ibis, a bird that is now extinct in Egypt. Its bluish color was associated with the sky, while the reddish color of its head represented the Sun. These attributes emphasized its celestial nature. In reality, the concept of the akh was primarily linked to the gods. It took shape after a person’s death and symbolized rebirth and resurrection in the afterlife.

During the Old Kingdom of ancient Egypt, the concept of the akh was primarily associated with kingship. Therefore, as divine beings, the pharaohs met with the gods after death, and their respective akh accompanied the solar god Ra on his eternal journey, traversing the sky and the underworld, sharing their power with the divinities.

Subsequently, with the “democratization” of death, common mortals also had the opportunity to transform into immortal beings, allowing them to partake in their own portion of eternity.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic