Khonsuemheb and the Ghost, a story written in ancient Egypt more than 3,000 years ago, tells the tale of a high priest of Amun named Khonsuemheb. The story is believed to have been written during the 19th and 20th dynasties of the New Kingdom, and may have been based on an earlier popular story.

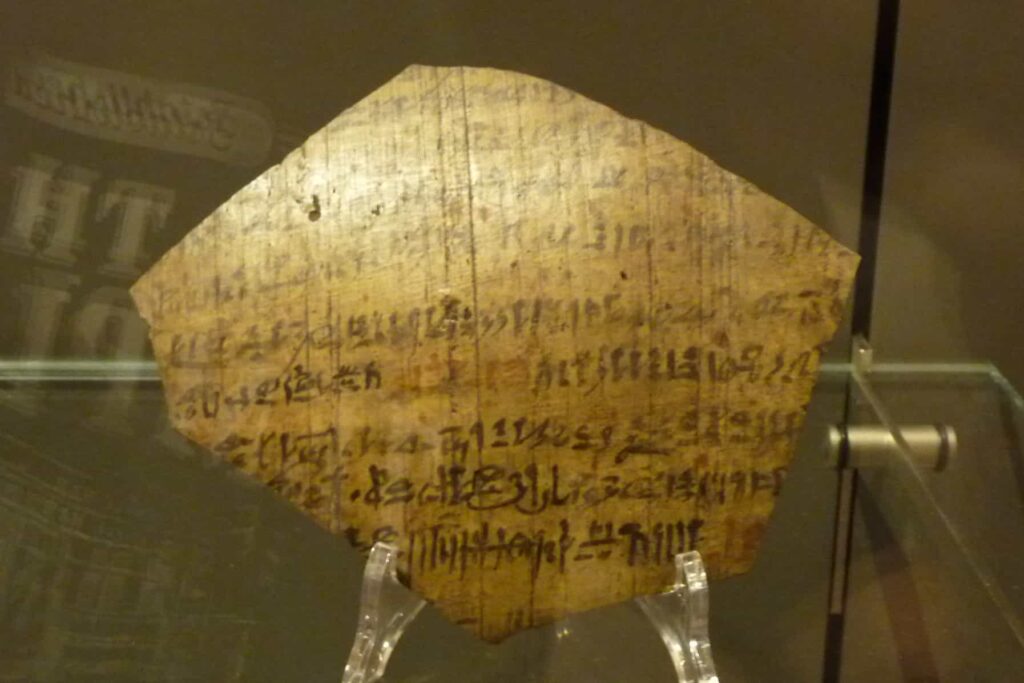

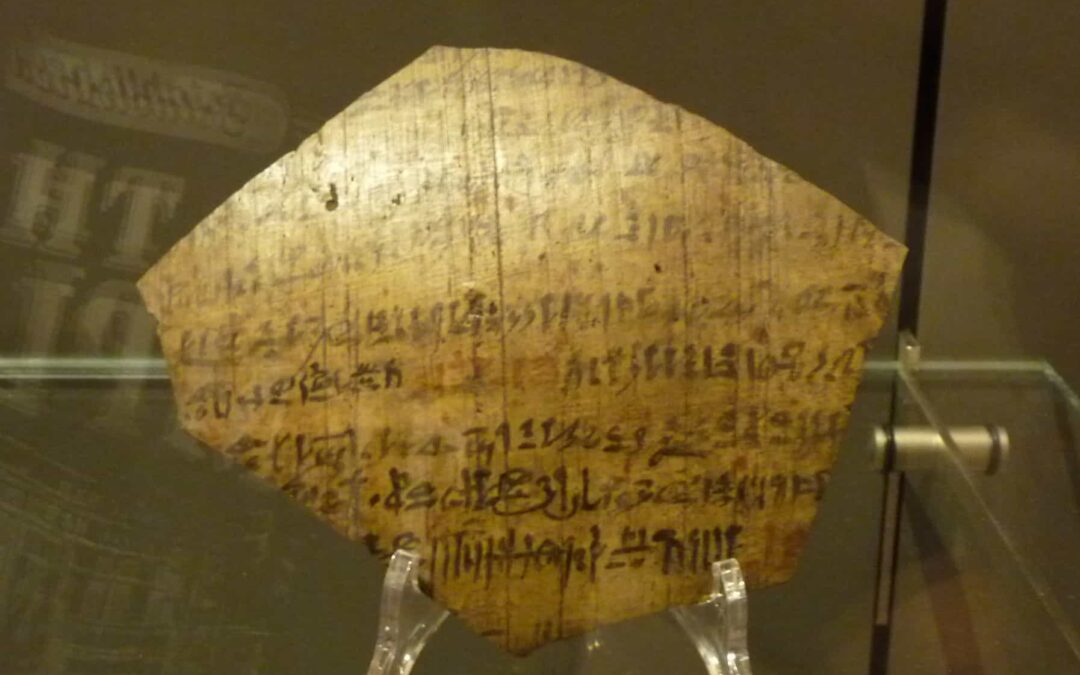

The story was found in various fragments of ostraca, which are ceramic or terracotta pieces on which scribes or their apprentices wrote texts or drawings. These fragments were discovered by Egyptologists such as Gaston Maspero and Ernesto Schiaparelli in the Deir el-Medina area between the 19th and 20th centuries.

The story begins with Khonsuemheb, the high priest of Amun, receiving a visit from a man who was forced to spend the night in the Theban necropolis. The man was awakened from his sleep by the akh, or spirit, of one of the deceased buried there.

According to ancient Egyptian beliefs, the human personality was multi-faceted and extended into a life after death. This allowed one of the forms adopted in the afterlife to return for various purposes, either positive or negative. This concept is not commonly seen in Egyptian literature.

The akh was the divine force linked to immortality and resurrection. It was initially exclusive to pharaohs, but later extended to the entire population. It was represented by a glyph in the shape of a crested ibis or a mummiform ushabti, which is a statuette.

After the death of the physical body, the ba and the ka come together to revive the akh, but this can become a kind of wandering ghost if for some reason the tomb is not in order, causing nightmares, remorse in the living, etc. Something that, as we are going to see, has a direct relationship with the story of Khonsuemheb and the ghost.

Taking up the thread of the ancient Egyptian narration, Khonsuemheb goes up to the roof of the temple and invokes the gods to get that spirit or akh.

Khonsuemheb and the Ghost

When he finally materializes, the spirit says his name is Nebusemekh, son of Ankhmen and Tamshas, who was a prominent figure in the court of Pharaoh Rahotep.

Rahotep reigned between the years 1622-1619 BC, belonging to the Seventeenth Dynasty, which belongs to the so-called Second Intermediate Period.

Nebusemekh, apart from holding a military command, served for Rahotep as overseer of the treasuries, an Ancient Egyptian official position that appears documented for the first time during the Fourth Dynasty and lasted until the Late Period (712-332 BC, approximately), the owner assuming the duties of administrator of the royal treasury.

The reason that Nebusemekh has returned from the afterlife is that his tomb (probably located in the Dra abul Naga cemetery, where Rahotep was buried and which is opposite the Karnak temple) has collapsed and the wind enters the burial chamber, preventing him from resting in peace.

He says he died during the reign of Mentuhotep, pharaoh Mentuhotep had given his official a tomb, a sarcophagus of alabaster and even the canopic jars (those that were used to store the viscera, after the mummification process), all of which were now in danger of ruin.

Taking pity on the poor ghost, the priest Khonsuemheb offers to help him, agreeing to repair his tomb and provide him with a new sarcophagus, this time made of golden jujube (a deciduous shrub endemic to the Mediterranean) wood. But Nebusemekh is not convinced of his sincerity because he has been deceived before.

To show his good faith, Khonsuemheb assures that every day he will send a dozen servants -five men and five women- to make offerings at the grave. Something commendable but useless, according to the ghost.

At that point, the narrative is interrupted, since, let us remember, it is found in several pieces discovered in Deir el-Medina (near Thebes) and distributed by the Egyptian Museum in Turin, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Florence and the Parisian Louvre.

The last fragment, the one kept in Paris, tells how Khonsuemheb keeps his promise and sends three servants in search of a suitable place to make a new tomb, finding it “twenty-five cubits away from the king at Deir el-Bahari” (where the funerary temple of Mentuhotep II stands, a famous place today because there, right next to it but five centuries later, Queen Hatshepsut and her son, the powerful Thutmose III, of the 18th dynasty, also built theirs).

No more pieces of Khonsuemheb and the ghost have been found. The last sentence says ambiguously: “And in the evening he returned to sleep in the Ne and he…” (the Ne is the Theban necropolis), which suggests that the high priest was going to inform Nebusemekh that he would soon have a new tomb. Would he be able to restore her to eternal peace?

Sources:

Jesús López, The Story of the Ghost (Khenshemhab and the Spirit)

William Kelly Simpson, The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry.