Obelisks, representing the rays of the sun god Ra, stood in temples and tombs throughout Egypt. Its construction and transfer constituted a titanic work that involved hundreds of people.

There is no doubt that the constructions that best identify the ancient Egyptian landscape are the pyramids and obelisks. In fact, they are monuments of a very similar nature.

Both were intended to impress with their height and to last forever; its construction required an extraordinary investment in labor and required a vast array of engineering; and they were loaded with religious and political symbols and messages.

Europeans were fascinated by pyramids and obelisks, but the latter had the advantage of being “transportable.” With that, the robbery of Westerners allowed various obelisks to end up as decorations for parks and squares in Rome, London, Paris, New York or Istanbul.

The term “ obelisk ” comes from the Greek obelískos, diminutive in turn of obelós, “pole or pointed column”. The ancient Egyptians called them weave.

The obelisks are monolithic pillars – made from a single block of stone – with four sides, and their shape is truncated pyramidal, that is, they taper slightly from the base to the top.

Its origin is the same as that of the pyramids; not by chance they were crowned by a small pyramid or pyramidion, called by the Egyptians benben.

This is a stylized representation of the primeval hill from Egyptian mythology, the mound that arose during the birth of the world and in which gods and living beings were created when nothing existed yet.

This legend developed in the city of Heliopolis, where the Sun was worshiped and the Benben stone was worshiped since the Archaic period (3065-2686 BC).

Perhaps in its origin this stone was a meteorite fallen from the sky, which acquired a sacred character because it came from the sphere of the gods.

In the Pyramid Texts, the hieroglyph representing the benben is a complete or truncated pyramidion, a double or single staircase, or a rounded-edged promontory; in all cases it appears as an element that rises from earth to heaven and serves as a connection between both worlds.

The benben symbolized the process by which the life-giving rays of the sun fall on the earth and fertilize it . For this reason, solar symbols and figures of the king protected by the solar god Ra or Amun-Ra were inscribed on the pyramidion.

The symbolic messages of the obelisks were not limited to the pyramidion. Hieroglyphic inscriptions were engraved on the four sides of the monolith, including a dedication to the gods and the names and titles of the pharaoh.

Through these texts, the monarch was united to the divinity and mediated between men and the gods. In 390 AD, the Roman Emperor Theodosius I took the obelisk of Thutmose III to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), where it is read that this king:

«He ordered the erection of many great granite obelisks, with their pyramidion, as a monument to his father the god Amun”.

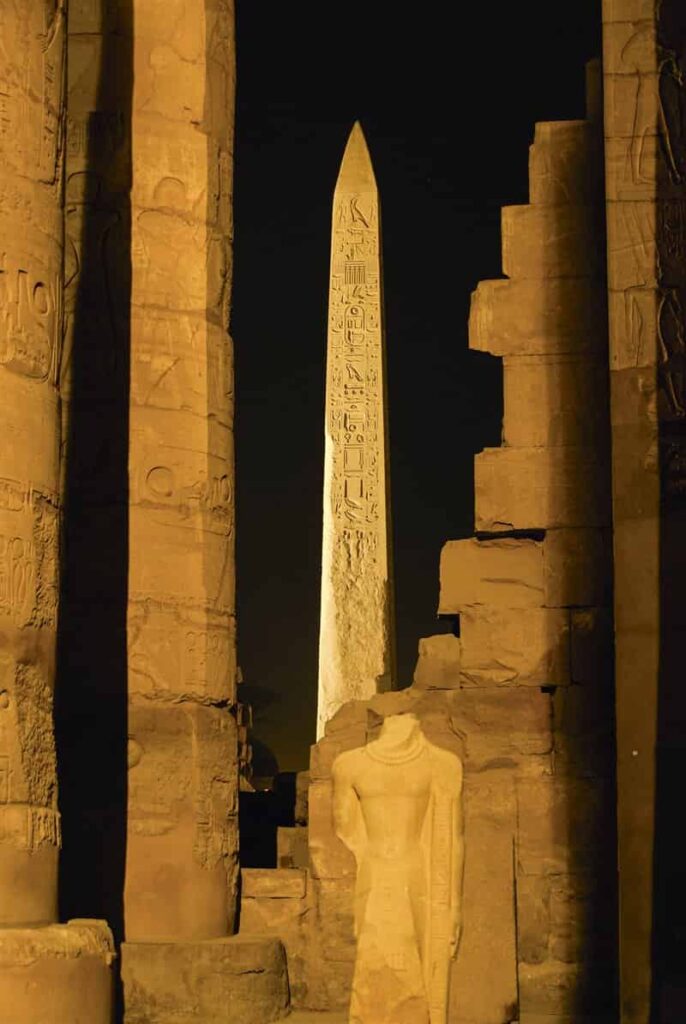

Likewise, the base of the obelisk could be adorned with baboons, animals associated with the Sun because of the cries that they utter at dawn and dusk, and which were interpreted as a tribute to the sun king.

This is how we see it in the obelisk of Ramses II that still stands before the monumental entrance to the temple of Luxor.

Solar temples and obelisks

According to ancient sources, some obelisks were covered with gold or an alloy of gold and silver, like that of Thutmose III.

However, it is most likely that the pyramidion that crowned it was simply lined with gold plate. The use of this metal is due to its durability and its relationship with the gods, whose flesh, according to the Egyptians, was made of this material.

Gold also had a special relationship with the sun, the color of this metal, whose rays propitiated and promoted life on earth.

The color of the stone was also linked to divine concepts. The most used material was the red or pink granite of Aswan, in the first waterfall, also linked to the Sun by its color.

Obelisks were present throughout the history of Egypt, from the Old Kingdom to the end of the Egyptian civilization, although they did not always have the same characteristics.

During the Old and Middle kingdoms, Heliopolis was the great center of worship for the sun god Ra, and it was for this reason that the obelisks were mainly built.

For example, Senusret I had two obelisks erected 20 meters high. The curious obelisk-stele of red granite that stood in Abgig, in the Faiyum Oasis, is due to the same Pharaoh, just over twelve meters high.

It is distinguished by its rounded upper end, rather than the traditional pyramidion, although the symbolism is identical.

Obelisks for the god Amun

In New Kingdom times, Thebes became a center of worship for the god Amun-Ra, who combined characteristics of the solar god Ra and the Theban god Amun.

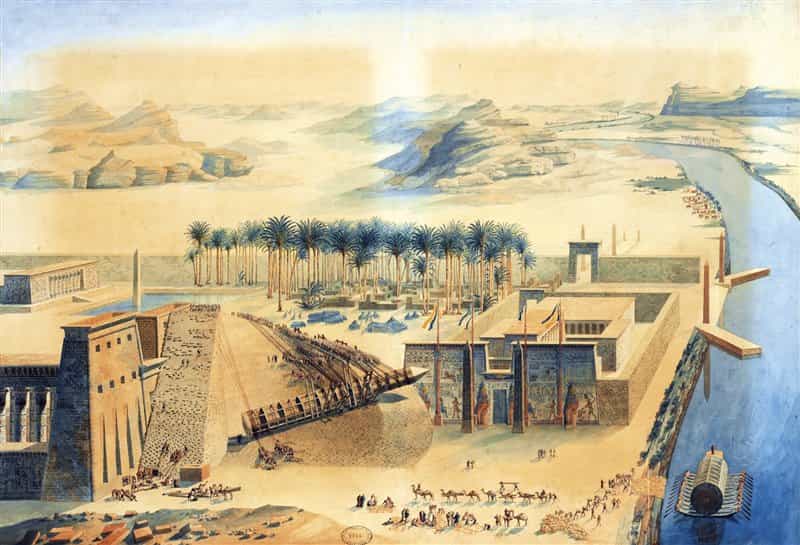

For this reason numerous obelisks were erected there, especially in the temple of Amun-Ra in Karnak and, to a lesser extent, in that of Luxor.

In fact, the New Kingdom was the peak period for the construction of obelisks, in which the most beautiful and tall ones were created, made with the most diverse materials: granite, quartzite, limestone, grauvaca…

Their silhouette appears on papyri, reliefs, paintings, and even amulets and jewelry.

Obelisks were erected in temples as a way of marking a “sacred” place. They used to be arranged in pairs before the pylons that flanked the doors of the sacred precincts.

In this way the dual aspect of the god Ra was manifested as the Sun and the Moon, since the Egyptians believed that the Moon was the nocturnal aspect of the king star.

In the Karnak temple, Thutmose I erected the first pair of obelisks, of which only one remains standing. In the same temple he was followed by two more from Thutmose II, two from Hatshepsut ( one of whom lies next to the temple’s sacred lake) and three from Thutmose III.

One of the latter must originally have reached 33 meters, which makes it the highest of those still standing.

Later, Thutmose IV erected another, like Seti I, although this king’s was smaller. For his part, Ramses II had a couple of new obelisks placed before the entrance of the newly built temple of Luxor; one of them was transferred to Europe in 1834 and today presides over the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

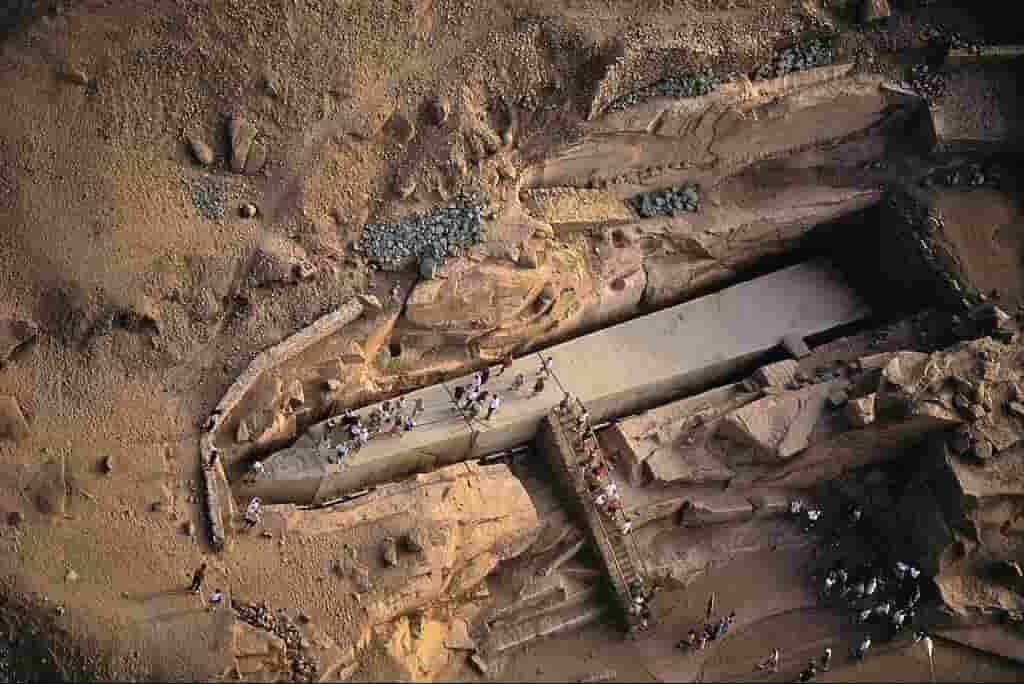

One cannot fail to mention the famous obelisk that was never erected because it was fractured in the Aswan quarry while the workers were carving it.

It is not known exactly which pharaoh ordered the work, but if it had been successful, with its almost 42 meters high and a weight of 1,168 tons it would have become the tallest and most imposing obelisk in Egypt.

It constitutes eloquent proof of the titanic effort involved in carving these huge blocks of stone from a single piece, then transporting them by ramps and sledges to the Nile, transporting them by boat and placing them at their final destination.

Obelisks for everyone

Not all the obelisks in Egypt were the work of the pharaohs, nor did they have the monumental proportions of those that stood at the Karnak temple.

There were also smaller “private” obelisks, which were placed in private graves. For its construction, the express authorization of the monarch was required, since he had a monopoly on the stone and only gave it as a gift or reward to a specific individual.

Read more: The unfinished obelisk of Aswan