Recent research indicates that, beyond mere conjecture, the pyramids of the Fourth Dynasty, constructed nearly 5,000 years ago, may possess a stellar alignment linked to the passage of the deceased pharaoh into the afterlife.

The ancient Egyptians were avid stargazers. Their system of timekeeping gave rise to the sophisticated solar calendar upon which ours is based, and they meticulously charted the stars, considering the firmament an integral part of their religious beliefs.

Moreover, they oriented their temples in pursuit of Maat, the cosmic order, refining astronomical patterns to aid in this endeavor.

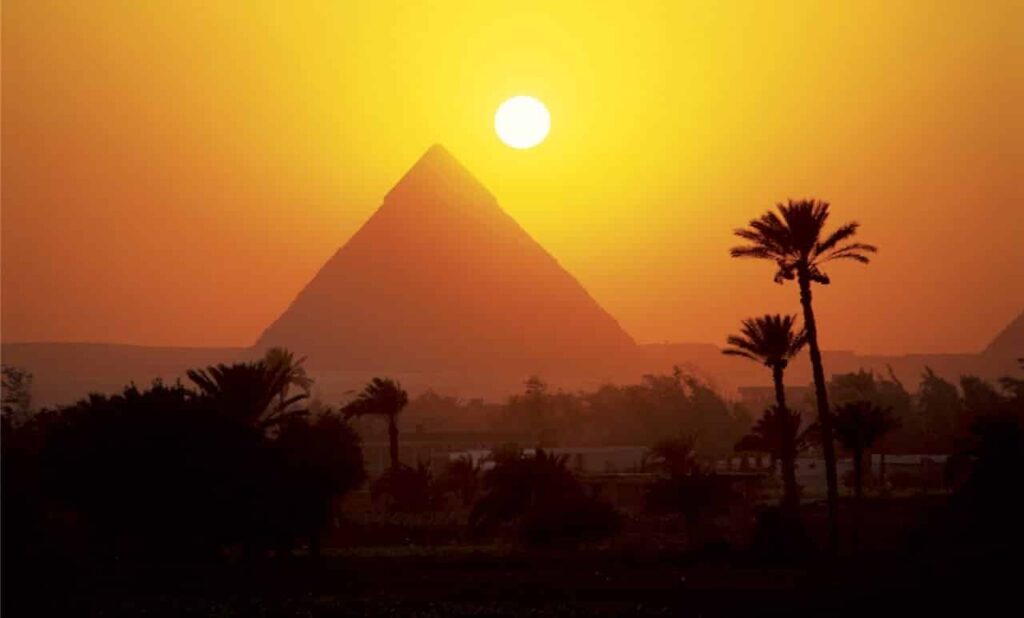

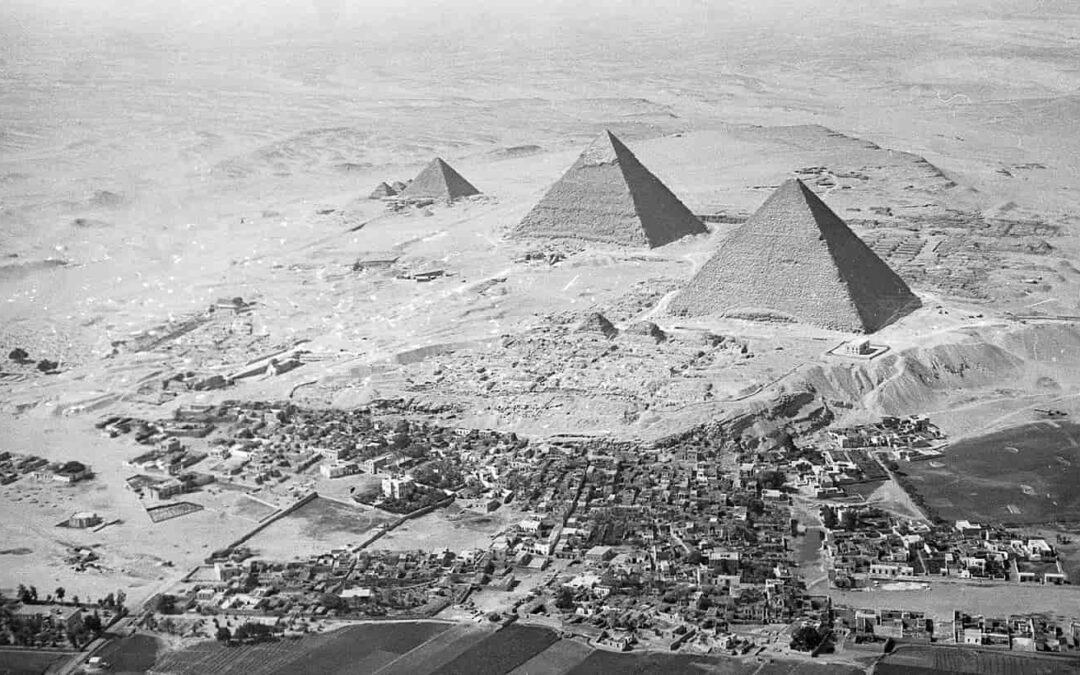

The profound connection between the heavens and the earth is also evident in the orientation of the pyramids. It is well-documented that these structures, particularly those erected on the Giza plateau by the pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure around 2550 BC, are aligned with the cardinal points.

The method by which they achieved this alignment remains one of the most hotly debated topics in the field of Egyptology.

The Significance of Meskhetyu

The ancient Egyptians referred to the constellation Ursa Major as Meskhetyu, identifying it as the Chariot asterism consisting of seven stars.

Represented either by a bull’s leg or by the ceremonial hoe used in the ritual of the opening of the mouth, a ceremony aimed at restoring the senses to the deceased, Meskhetyu held great importance from ancient times.

Its prominence is evident in the Pyramid Texts, the oldest known religious texts, which adorned the burial chambers of numerous pyramids as early as 2300 BC.

Within these texts, phrases such as “I am the one who lives, […] the two Enneads have purified themselves for me in Meskhetyu, the Undying” convey the deceased king’s aspiration to ascend to the heavens and join the ranks of the “imperishable stars,” specifically the circumpolar stars that remain perpetually visible in the night sky.

The alignment of the pyramids, coupled with their association with celestial motifs such as Meskhetyu, underscores the profound cosmological beliefs of ancient Egypt, where the earthly and celestial realms intertwined, offering insights into the mysteries of the afterlife and the eternal journey of the soul among the stars.

This concept can be traced back, at the very least, to the onset of the Old Kingdom, as noted by the author, with reference to the stepped pyramid of King Djoser in Saqqara, constructed around 2650 BC. However, it’s plausible that it reflects even older traditions, potentially dating back to the Predynastic period around 3100 BC.

The deep connection between Meskhetyu and royalty, intertwined with the celestial realm, reveals another dimension. An inscription from the temple of Edfu, dating back to the 3rd century BC, states: “By observing Meskhet [yu], I have established the four corners of the temple of his majesty,” indicating that the temple was aligned in accordance with the visibility of Meskhetyu on the horizon.

Alignment was accomplished through the ritual of “tightening the rope,” during which the king, accompanied by the goddess Seshat, associated with time reckoning and writing, determined the orientation and dimensions of a temple through specific observations, likely of an astronomical nature.

Indeed, the practice of using stars and celestial bodies to orient sacred structures has been documented since the earliest days of Egyptian civilization, much like the ceremony of tightening the rope itself, mentioned in the records of a ruler from the First Dynasty.

In particular, Meskhetyu consistently served as a reference point for the Egyptians to establish meridian orientations, based on stars visible along a meridian—the imaginary line dividing the celestial sphere into eastern and western halves, running from north to south.

The Pyramids and Celestial Alignment

Not all of Egypt’s pyramids are precisely oriented; in fact, only a handful of the over sixty known pyramids exhibit accurate alignment.

Among the pyramids of the Fourth Dynasty pharaohs at Dahshur and Giza, the alignment is most precise, with errors of approximately a quarter of a degree, or 15 minutes of arc. Some, like those of Khufu and Khafre, exhibit even less error.

Considering that the sun or full moon, as observed with the naked eye, have a diameter of about 36 minutes of arc, it becomes evident that such precise results would only be achievable through the expertise of highly trained observers equipped with the most accurate instruments available at the time.

It’s intriguing that the oldest pyramids boast the best alignment. Various theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, many centered around the use of astronomical observations to establish the north-south axis.

In the 19th century, astronomer Piazzi Smyth suggested that the Great Pyramid may have been aligned with Thuban, which at that time served as the pole star—the star nearest to the celestial pole visible to the naked eye.

This theory found support from Heinrich Karl Brugsch, a prominent Egyptologist of the era. Thuban reached its closest position to the pole around 2787 BC, when it was only two arc minutes away from it.

However, it was later discovered that the Great Pyramid was built at least two centuries later than previously believed, rendering this theory improbable.

Other proposed orientation methods involve observing the sun or the shadows it casts. In 1931, Ernst Zinner suggested observing the minimal shadow produced by a gnomon—a stick inserted vertically into the ground—since, in our hemisphere, the shortest shadow cast by the sun at noon points northward. However, accurately outlining shadows proved challenging, making achieving the required precision difficult.

In the late 20th century, American artist Martin Isler proposed that certain techniques available in ancient times may have enabled the precise shaping of shadows.

Building upon this idea, archaeologist Glen Dash, a member of the Giza Plateau Mapping Project, recently conducted experiments demonstrating that the “Indian circle method” could potentially achieve the necessary precision by tracking the displacement of the solar shadow throughout the day. However, there is currently no evidence that the Egyptians were aware of this method.

A Fundamental Discovery

In the 1980s, astronomer Steven C. Haack made a significant observation regarding the orientation of the pyramids from Dynasty IV and those constructed before and after. He noted a temporal correlation in the errors of their alignment.

Haack found that the older pyramids displayed less precise orientation compared to later ones. Alignment errors reached a minimum during the reign of Khufu but increased again in subsequent monuments. Haack attributed this surprising pattern to the phenomenon of precession—the gradual change in the Earth’s axis of rotation over time.

Despite the importance of his discovery, Haack’s postulation that the pyramids were aligned based on the orthography of certain stars—meaning the point at which they appear in the sky—did not receive much recognition. This method was later proven to be insufficiently accurate.

Instead, the method proposed by IES Edwards in 1947 gained more support within the scientific community. This approach involves first establishing an artificial horizon, such as a stone wall, to mitigate issues caused by atmospheric extinction and refraction near the horizon.

Then, a circumpolar star is selected and observed during its nightly movement. The positions of its rise and set are marked on the artificial horizon, indicating the precise north-south meridian line.

Although this procedure is believed to be highly accurate, it has not yet been experimentally tested, and there is no evidence of its historical use.

Once again, this underscores the complexity of the architectural plans devised by the pyramid builders, which intertwined practical considerations with religious symbolism. In this instance, the alignment of the pyramids reflects the intimate connection between circumpolar stars and the belief in the afterlife of the deceased pharaoh.

While the problem of pyramid orientation remains unsolved definitively, these discoveries shed light on the intricate knowledge and symbolism embedded within these ancient structures.

Sources:

Juan Antonio Belmonte, National Geographic.

Pyramids, temples and stars. J. Antonio Belmonte. Criticism, Barcelona, 2012.

Astronomy in ancient Egypt. Jose Lull. University of Valencia, 2004.