On November 26, 1922, the English Egyptologist Howard Carter anxiously peered through a small hole he had just made in the intact door.

Behind it lay the antechamber where the objects from King Tutankhamun‘s funerary trousseau were piled up. When Lord Carnarvon, his companion and patron, asked if he could see anything in the dim candlelight, Carter simply replied, “Yes, wonderful things.”

Three days later, the official opening of the tomb took place before distinguished figures, privileged witnesses to what many already described as the most significant archaeological discovery of the century.

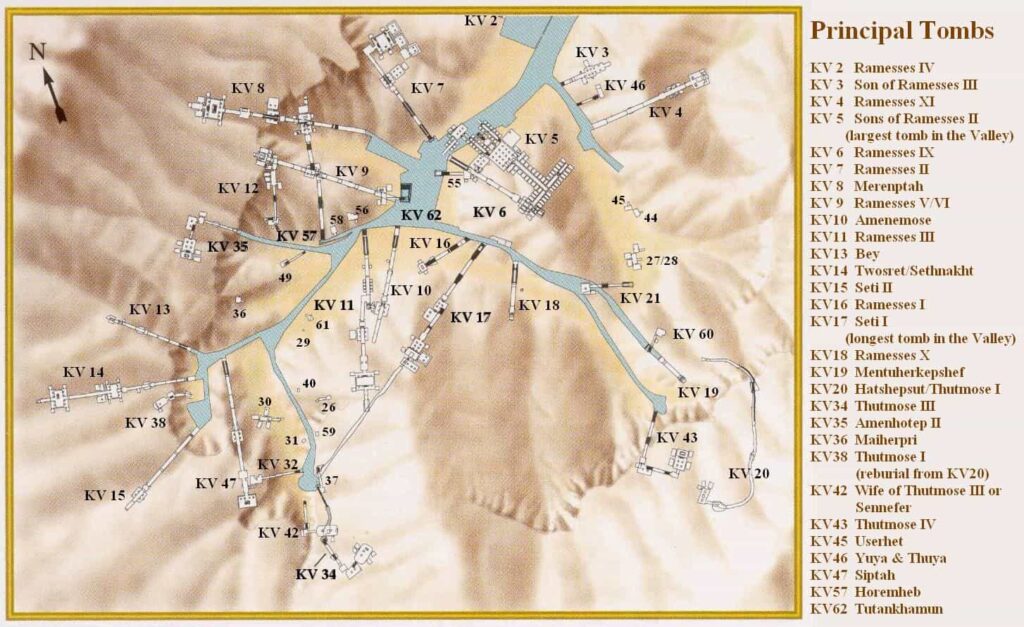

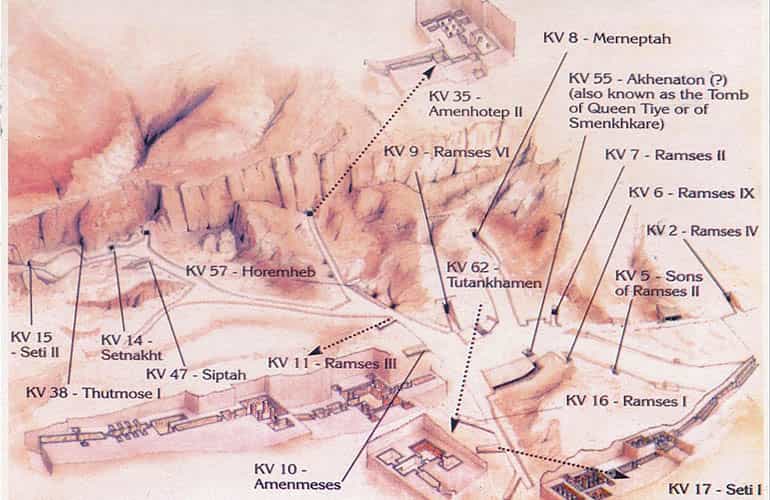

The site that had served as the eternal resting place for the pharaohs of the New Kingdom was reclaiming its prominent role in history.

The necropolis was carved into the mountainous slopes of the west bank of the Nile, overlooking present-day Luxor. The ancient Egyptians referred to this area as “the place of the gods west of Thebes.”

Established by the kings of the 18th dynasty, it remained active until the end of the 20th dynasty. Its origins, expansion, and eventual abandonment reflected funeral customs developed during one of Egypt’s most splendid periods.

The location, architecture, and decoration of the tombs were imbued with significant magical and religious symbolism.

In pursuit of eternity

The tomb represented the pinnacle of importance in the life of ancient Egyptians, wherein they poured all their efforts. It wasn’t just a resting place for their remains but was conceived as a sacred space essential for ensuring survival in the afterlife.

This belief stemmed from the notion of transcending death through continuous and eternal rebirth.

However, the fate reserved for the Egyptian king differed significantly from that of ordinary mortals.

While the afterlife for others was envisioned as an idealized version of earthly Egypt, accessed after successfully passing the Judgment of Osiris, the pharaoh’s destiny lay in the heavens, alongside the gods.

For the king, death marked merely the beginning of regeneration, with the tomb serving as the architectural stage for this transformation. The departed king would ascend to the heavens and unite with the sun disk.

The monarch of the New Kingdom was closely associated with the deity Osiris. This god, the king of gods, underwent death and resurrection through the magic of his wife Isis, eventually ruling over the realm of the dead.

The entrance of the deceased king into his tomb symbolized the journey into the underworld under Osiris’s dominion, from which he would emerge reborn like the sun at dawn. The delicate interplay between solar and Osirian elements characterized the tombs of the Valley.

The birth of the valley

Construction on a king’s tomb commenced immediately following their coronation, overseen by a high official or the vizier. Upon the monarch’s demise, there remained a mere 70 days, following the completion of the embalming process, to finalize arrangements for the transfer of the mummy and the installation of the funerary trousseau.

The kings of the 18th dynasty selected an area within the Theban mountains for their burial site, characterized by a striking pyramid-shaped peak sculpted by erosion.

This location was chosen for its proximity to the city of Thebes, which had been designated as the new capital of Egypt. Throughout the New Kingdom, the Theban region emerged as a significant sacred space, intimately connected on both its eastern and western shores.

On the eastern shore stood the Temples of Karnak and Luxor, while the western shore boasted the most prominent necropolises of the period: The Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens, and the Valley of the Nobles.

For the first time, the funerary temples, where rituals honoring the deceased king were conducted, were separated from the tomb and constructed on the adjacent shore, albeit in the plain area.

The royalty opted to excavate their tombs in the ancient valleys of the desert, sheltered by the protective embrace of two goddesses: Hathor, known as “the lady of the west,” and Meretseger, referred to as “the one who loves silence.”

The rugged terrain, marked by steep slopes and towering cliffs, provided an ideal backdrop for implementing the new funerary concepts that would characterize the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

The kings commissioned specialized workers for the construction of their tombs, laying the foundation for what would become the artisan village known as the “Place of Truth,” present-day Deir el-Medina, located just a few kilometers from the Valley.

These craftsmen were skilled stonemasons, adept at quarrying limestone strata and devising solutions for unforeseen challenges. Tombs like that of Hatshepsut demonstrate their ability to alter tunnel directions in response to the natural rock formations.

The bustling activity within the Valley necessitated a well-organized workforce, with laborers divided into two teams of 70 men each, working in alternating 10-day shifts.

The royal tombs underwent continual evolution throughout the New Kingdom, mirroring the religious developments introduced by successive dynasties.

This evolution was influenced by factors such as location and design, resulting in simplified layouts, expanded sizes, and increasingly elaborate decorations.

The Sun’s Journey

Upon the pharaoh’s death, the funeral procession embarked on a solemn journey from the eastern bank of Thebes to the western bank.

As the sun dipped below the horizon, casting long shadows across the land, the royal mummy traversed the mountains and descended into the Valley of the Kings, mirroring the path of the setting sun.

Thus commenced the quest for the rebirth of the deceased king, intricately linked to the fate of the sun god Ra. The royal tomb served as the architectural embodiment of Ra’s voyage through the underworld of Osiris.

Hence, the chosen tomb type was subterranean, hewn into the rock—a practice pioneered by the kings of the Seventeenth Dynasty. The pyramid tomb design, once inspired solely by solar symbolism, was definitively abandoned.

From the tomb’s entrance to the sarcophagus chamber, the pharaoh followed the sun’s path. Passing through the threshold, a series of corridors and stairways replicated the sun’s daily journey across the sky, from dawn to dusk and back again.

Each corridor bore a name signifying its role in this celestial voyage—the “first path of the sun,” the “second path of the sun,” and so forth—symbolizing the pharaoh’s symbolic union with the solar deity.

The initial tombs of the 18th dynasty emphasized the symbolism of Osiris, serving as gateways to the depths of the underworld by carving steeply sloping corridors into the heart of the mountain.

Queen Hatshepsut’s tomb, the longest in the Valley spanning over two hundred meters, descended nearly one hundred meters into the earth. It featured a distinctive “L” shaped shaft design.

Subsequently, the tombs of the Ramesside period reimagined this concept, favoring a straight east-west axis to underscore their solar symbolism, mirroring the trajectory of the sun.

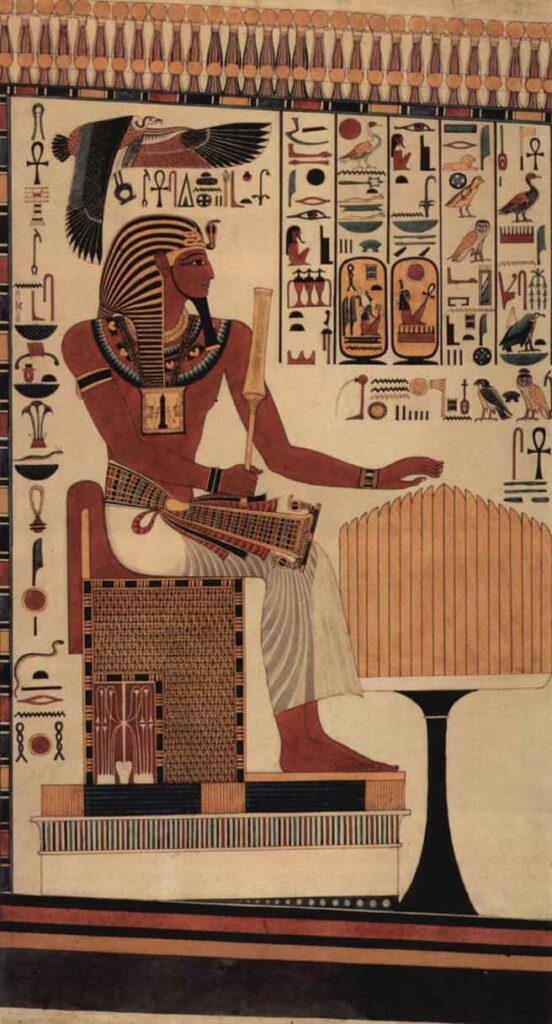

The ceilings, painted blue and adorned with stars, depicted the sun’s daily passage, transforming from a radiant yellow disc resembling a scarab to its nocturnal manifestation as an aged god with the head of a ram.

At the far end of the tomb lay the chamber housing the royal sarcophagus. Supported by four pillars, it was typically rectangular, though sometimes taking on a cartouche shape. Dubbed the “Room of Gold,” it symbolized the site of the king’s ultimate regeneration.

In certain tombs like that of Tutankhamun, the walls were painted yellow, evoking the sun’s radiant appearance. The sarcophagus was often positioned transversely within the chamber, although by the 20th dynasty, it was symbolically aligned with the linear solar axis. The ceiling depicted a celestial canopy.

The tomb of Seti I introduced an astronomical ceiling adorned with representations of constellations and elements of the calendar, marking the first occurrence of such artwork in the Valley.

In 1817, when Giovanni B. Belzoni, one of the Valley’s renowned adventurers, uncovered Seti I’s tomb, he already regarded it as one of the necropolis’s prized jewels.

Landscapes of the Beyond

The decorative scheme was meticulously tailored to the tomb’s architecture and strictly adhered to. During the 18th dynasty, decoration was limited to specific chambers, whereas in the Ramesside period, it encompassed all surfaces.

Wall paintings depicted Ra’s nightly odyssey through the underworld. This journey, undertaken by the sun god aboard a celestial vessel along an underground river, mirrored the solar voyage across the Nile.

Throughout this journey, Ra was accompanied by fellow deities who aided him in his daily triumph over adversity.

The scenes depicted in these wall paintings drew inspiration from specially crafted compositions designed for the king. These funerary “books” served as intricate guides to navigating the subterranean realm, detailing its geography and offering essential insights into overcoming obstacles encountered along the way.

One recurrent theme was the rituals for defeating the serpent Apophis, the embodiment of chaos and Ra’s eternal foe. Each night, Apophis was vanquished, only to rise again at dawn.

Central to these compositions was the “Book of the Amduat,” which chronicled the sun’s journey through the underworld’s twelve night hours, corresponding to twelve regions. At the final hour, the sun emerged anew over the horizon in the guise of a serpent, symbolizing rebirth. The sarcophagus chamber symbolized the culmination of this journey at the twelfth hour.

Building upon the foundation of the “Book of the Amduat,” another significant work emerged: the “Book of the Doors.” Here, each hour was marked by a gate guarded by spirits and fire-breathing serpents. The “Book of Caverns” elaborated on this vision, portraying a succession of caverns and passages the sun traversed.

Additional texts, such as the “Litany of Ra” and the “Book of Heaven,” flourished during the Ramesside period, envisioning an increasingly intricate afterlife for the king.

The Sealing of the Tomb

The burial rites of the pharaoh were overseen by the succeeding king, seen as an act of validation. Therefore, King Ay took charge of organizing Tutankhamun’s tomb and overseeing the funeral proceedings.

In the burial chamber, King Ay was depicted performing the ritual of “opening the mouth” on the young monarch’s mummy. This ritual aimed to restore the physical faculties necessary for speaking and eating in the afterlife.

The pharaoh’s funerary equipment consisted of objects intended to serve him in the hereafter, including food offerings, furniture, jewelry, and ritual figurines, all imbued with magical and religious significance.

However, the centerpiece was undoubtedly the sarcophagus. The mummy was placed within a series of wooden coffins, which were then placed inside a rectangular stone sarcophagus. Unfortunately, most sarcophagi were looted or moved over time, with only those of Thutmose I and Thutmose III remaining intact.

Adjacent to the sarcophagus were the canopic jars, housing the organs removed during the mummification process.

Once the sarcophagus was positioned in the chamber and a ritual banquet held, the successive corridors and rooms were sealed shut with large stone slabs, marking the final closure of the tomb.

Decline and Abandonment

Despite the Ramessides relocating the capital to Memphis, Thebes retained its status as a religious center, with tombs continuing to be constructed in its necropolis.

The most recent burial discovered in the Valley is attributed to Ramses XI, although it was left unfinished.

Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the Valley of the Kings experienced a period of turmoil, marked by political instability and economic downturns during the latter reigns of the 20th dynasty.

Surveillance in the necropolis diminished, leading to a surge in uncontrolled grave robbing. Many of these looting operations were facilitated by complicit workers from Deir el-Medina.

Discontent among the artisans resulted in numerous protests, including a significant strike in the 29th year of Ramses III’s reign.

The vulnerability of the necropolis had been evident since the early New Kingdom period. Tutankhamun’s tomb was repeatedly desecrated shortly after its sealing. Some tombs were looted even before their intended occupants were interred, as was the case with Seti II.

The scandal reached its peak during the reign of Ramses IX, who initiated numerous legal proceedings against offenders. Various papyri documented the trials and subsequent convictions, revealing the corruption among high-ranking Theban officials.

The weakened authority of Ramses XI allowed the High Priest of Amun in Thebes to authorize widespread looting of the Theban necropolises to fund temple expenses.

This era of instability ultimately led to a political division, ushering in the Third Intermediate Period in Egyptian history.

The northern regions fell under the control of the Twenty-first Dynasty, which established its own necropolis in the new capital of Tanis. Thebes and southern Egypt came under the jurisdiction of the High Priests.

As a result, the Valley of the Kings was abandoned by the pharaohs, utilized only sporadically for non-royal burials. With dwindling opportunities for employment, the community of Deir el-Medina gradually evacuated the area.

The clergy of Amun began a gradual dismantling of the royal tombs, engaging in a paradoxical endeavor: reverently restoring the royal mummies while simultaneously seeking the riches contained within.