Geography greatly influenced the way the ancient Egyptians understood the origin and reality of their world.

Thus, the marked contrasts offered by the landscapes of the Nile and those of the desert, for example, or those of the river valley and those of the delta, weighed on their conception of the universe in dual terms, opposite in appearance, but complementary in reality. However, not only geography defined this conception of the world.

Temporal contrasts (the succession of day and night) and biological contrasts (male and female genders of animals and human beings, for example) operated in the same way as landscape ones.

The continuous repetition of natural cycles (such as vegetation, lunar and solar cycles) and other phenomena (such as the annual flood of the river or the reappearance of the star Sirius after 70 days of hiding) led the Egyptian to believe in the periodic regeneration of nature and to conceive the hope of reviving after death thanks to rites that allow it to be integrated into such cycles.

As for their king, the ancient Egyptians saw in him an individual with a personality whose aspects were complementary. Their names, their iconography and different types of texts reveal this.

First of all, the king was first and foremost the earthly incarnation of the falcon god Horus, the great god of the sky. When an incarnation of Horus died, the god passed on to the next king, and the dead sovereign was identified with Osiris, the divine father of Horus.

From the 4th dynasty the pharaoh is mentioned as the carnal son of the sun god, Ra. In their tombs, on the other hand, other dualities were reflected: the union of earth and sky, the succession of death and rebirth …

The essential functions of the monarch were to ensure the sustenance and supply of the population, to maintain the divine worship, guarantee justice and defend the borders from any possible external attack.

Activities all of them that could be summarized in the maintenance of the Maat: the ideal state of order, truth and justice.

Soon an increasingly complex administration would develop around it, which already in the Old Kingdom (2575-2150 BC ) knew a high degree of specialization.

It was this sophisticated structure that made it possible to undertake the construction of the pyramidal complexes, since they involved the concentration, management and distribution of an immense amount of material and human resources.

After the Sixth Dynasty, that Egypt went into decline. The monarchy has been weakened against the provincial aristocracy, and the country suffers an internal division into different political units.

Apparently, a gradual drying process took place that would result in less abundant floods and an increase in aridity. The availability of agricultural surplus was greatly diminished, and with it the wealth and supply capacity of the country, problems that the central administration could not cope with.

After its end, the Old Kingdom remained in the imagination of later Egyptians as the classical age par excellence, a glorious period to which they constantly referred, seeking keys to face the challenges of their present and better understand themselves.

The Third Dynasty of Ancient Egypt

He is the successor of Khasekhemwy (last sovereign of the Second Dynasty), Djoser, who inaugurates the Third Dynasty and, with it, the Old Kingdom.

The political figure of the vizier (character who acts as a kind of prime minister), created in the previous dynasty, is consolidated, and the administrative division is created into provinces (nomos), led by a nomarch, or provincial chief.

The figure of the king begins, although still very embryonic, to acquire elements that link him, identifying him, with the sun god, Ra.

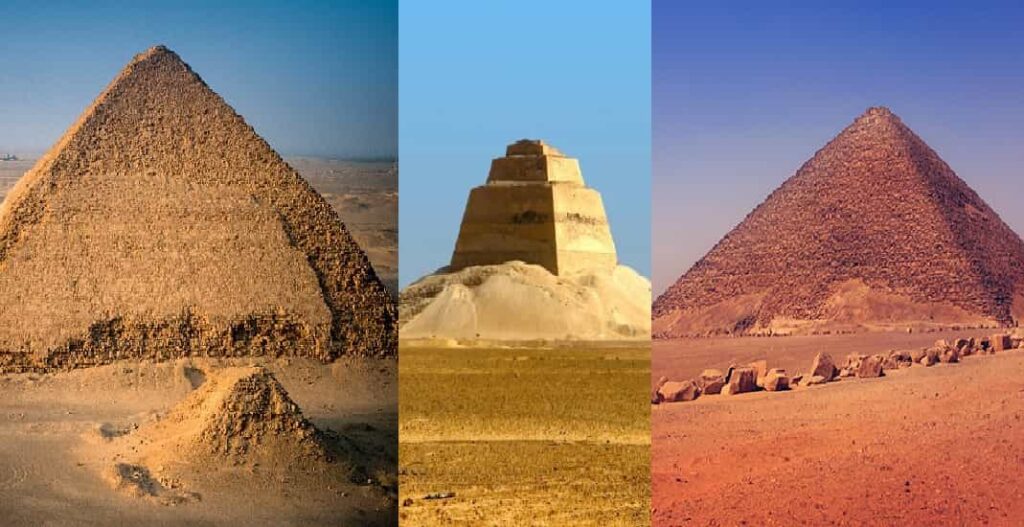

The main symptom of this solarization of the pharaoh is visible in the creation, for the first time, of a stepped pyramid as a royal tomb.

In Saqqara, in the funerary complex of Djoser, a ladder allows him to ascend to heaven and join Ra, who crosses the celestial vault daily in his boat.

The following kings will imitate his model, reflecting the continuity of religious ideas. The end of the dynasty is represented by the reign of Huni.

This, without our knowing why, locates his palace and funeral complex further south, in Meidum, while Memphis remains the capital.

It is not clear if the small pyramids that are erected in the provinces for the worship of the king are built by himself or his successor, although they do express the interest of the State to be present in the provinces.

In the same way, it is possible that at the moment the court is itinerant, that is, it does not know a fixed seat, which allows it to closely monitor such a long country, as well as fulfill its religious obligations, by participating in festivals of the different regions.

The Fourth Dynasty of ancient Egypt

The next dynasty begins with what was probably Huni’s son, Sneferu. During the dynasty that he inaugurated, important advances appeared in the theology that defines the figure of the pharaoh and that strengthens his relationship with the god Ra.

In Sneferu‘s reign, the stepped pyramid was changed to one with smooth faces, more of a solar than celestial character.

New iconographic elements related to the sun appear (such as the cartouche that surrounds the royal names or different crowns).

There is general agreement when saying that his reign (and those that follow) is the zenith of the administrative centralization of the State.

In addition to his Meidum Pyramid, or the probable construction of small provincial pyramids, he built two pyramid complexes in Dahshur, which gives an idea of his great concentration of resources.

With Sneferu we are also witnessing the beginning of a characteristic process of this dynasty: The occupation by members of the royal family of all positions of responsibility in the country, such as the visirate and high positions of the civil or religious administration.

Sneferu’s successor, Khufu, built the largest and most complex pyramid of the Old Kingdom, the Great Pyramid, at Giza, a new necropolis further north.

Some authors provide convincing arguments to think that, following the process of solarization already begun in the Third Dynasty, this king was divinized in life, identifying himself with Ra.

Khufu is followed by Djedefre, who will be succeeded by his half-brother Khafre. Both are protagonists of changes.

With the first, the title Son of Ra is established. With the second, a series of transformations in the building of the funerary complex.

Menkaure, Khafre’s son and successor, will build a pyramid of much more modest dimensions, at the same time that a greater concern for the provinces is evident.

There seem to be strong changes and a certain instability in the reign of Menkaure’s successor, Shepseskaf, who is buried in Saqqara and, more significantly, abandons the pyramidal shape in exchange for an immense mastaba in the form of a sarcophagus.

The Fifth Dynasty of ancient Egypt

With unclear ties to the pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty, the founder of the 5th, Userkaf, who will reign for a short time, ascended to the throne. However, with him certain changes are already being undertaken.

Thus, he inaugurates a trend shared by the sovereigns of the first part of the dynasty: the construction of solar temples in the vicinity of the royal burial place.

Their ties to the previous monarch are manifested not only in the similar structure of their names, but also in the choice of a burial site close to his own.

The successors of Userkaf will move their burial site to Abusir, which is established as a royal necropolis and site of construction of the solar temples until practically the end of the dynasty.

From this moment on, a certain relaxation of political and administrative centralization became evident (perhaps already present since the reign of Menkaura).

The provinces are made more involved in the country’s politics, with a somewhat more uniform distribution of resources.

In parallel, the nobles, who are now beginning to sculpt their autobiographies on the walls of their tombs, see their presence and influence grow at court.

This takes place because the royal family no longer monopolizes the main positions. The mastabas in which these nobles are buried are getting bigger and better decorated.

As a consequence of this process, the Crown, very slowly and progressively, will lose economic capacity and space for political action.

Some changes are visible at the end of the dynasty, when Djedkare prefers to leave Abusir to bury himself at Saqqara, and at the time when he is no longer building any solar shrines.

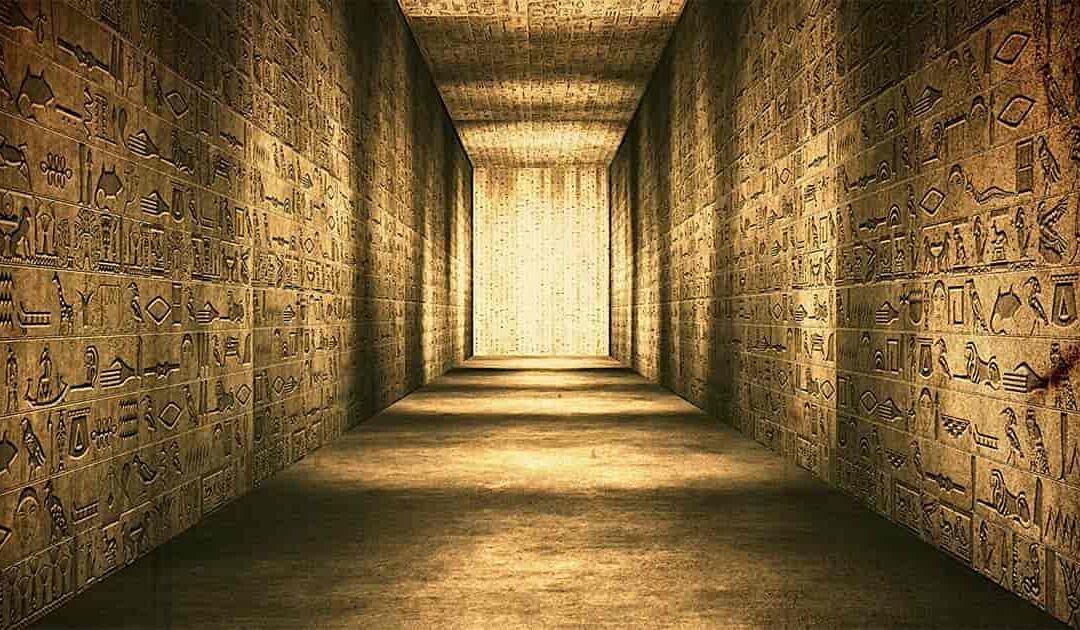

The sense of change becomes clearer when the last king of the dynasty, Unas, abounds in this trend and has a series of enchantments inscribed in his tomb, for the first time, designed to ensure his survival in the afterlife.

They are what has come to be known as the Pyramid Texts, and it is not very clear what caused such an outstanding novelty.

During the Fifth Dynasty it seems that Egypt opens a little more to the outside. The previously established relations are maintained, while now contacts are initiated with the Punt and with the Aegean region.

The Sixth Dynasty of ancient Egypt

Unas’s successor, Teti, inaugurates the Sixth Dynasty. According to the latest research, at his death, a usurper, Userkare, seems to reign for a very short time, who is abruptly and violently evicted from power by Teti’s son, Pepi I.

Pepi I undertakes a series of important administrative reforms and strengthens a multitude of provincial cults.

In parallel, the provincial governors (nomarchs) see their power increase to such an extent that they make their positions hereditary.

They are buried not next to the king, guarantor of the afterlife, but in the provinces where they rule. A very clear example of this process is the marriage of Pepi I with two daughters of Khui, nomarch of Abydos, something unprecedented.

It is an example of the considerable power and influence (and, to some extent, autonomy) that these characters were beginning to display, who were interested in keeping a close eye on them.

This is a turbulent time. Thus, within the harem several conspiracies take place against Pepi’s life, which he managed to quell before they fulfilled their objective.

Also remarkable is the reign of Pepi II, who came to power as a child and remained in it, according to the most generous attributions, for around ninety years.

Such a long duration was a serious dynastic problem, when the king’s own successors died. Under his reign, the prerogatives and capacities for action of the clergy and the already established provincial nobility increased, to the detriment of the power of the pharaoh and the central administration.

At the end of the 6th dynasty, in the absence of a successor, a queen, Nitocris, took power.

After her brief reign, the so-called First Intermediate Period takes place, in which the country is divided into different political units.