Driven by the desire to perpetuate his glory for eternity, Ramesses II erected monuments throughout Egypt, including his magnificent funerary temple, the Ramesseum, on the west bank of Thebes.

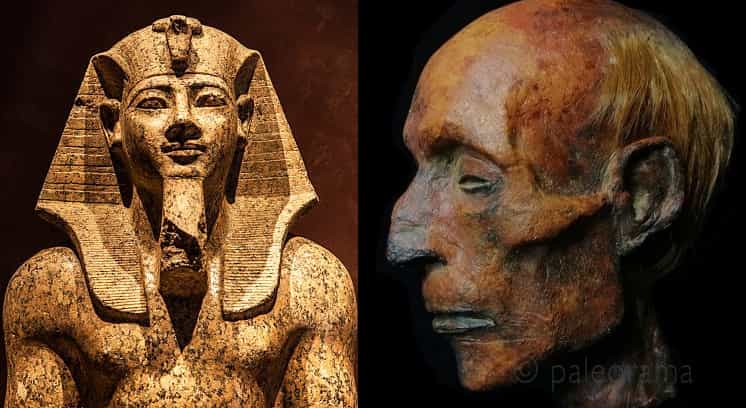

Ramesses II, third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, was crowned in 1279 BC “as King of Egypt on the throne of Horus”, according to the sources of the time.

During his reign he undertook an unprecedented constructive program. The country was filled with new religious buildings, in which the various names of the sovereign appeared, as well as the image of the king dispensing justice, honoring the gods or on the battlefield, as the architect of real or supposed victories.

It seems that in Egypt there was no corner where the king was not immortalized in stone to ensure his memory beyond death.

At Abydos he completed the work of his father Seti and built his own temple; he founded and enlarged sanctuaries in various places, including Thebes, Karnak, and Luxor.

To consolidate his presence in Nubia he built several temples there, among which Abu Simbel stands out, this one dedicated to Amun, Ra-Horakhty, Ptah and to the deified Ramesses himself.

There, in Abu Simbel, he dedicated a smaller temple to his wife Nefertari, associated with Hathor. He also had stelae and inscriptions carved, obelisks erected, and statues carved, which he planted throughout his domain, beyond the Nile Valley, from Nubia to Libya and Palestine.

Ramesses was a master at the use of propaganda, and in order to magnify himself he did not hesitate to usurp buildings, inscriptions and statues of former pharaohs, including his own father, Seti I.

To keep an eye on the northern frontier, always threatened by incursions of Libyans or peoples of the Near East, and to get away from the powerful clergy of Amun in Thebes, he moved the capital of Egypt to Pi-Ramesses, a small city in the Delta founded by his grandfather, Ramesses I.

Pi-Ramesses came to accommodate some 300,000 inhabitants and Thebes was relegated to religious capital.

The temple of millions of years

Among all the buildings of Ramesses II there was one that was especially dear to him. It was erected precisely in Thebes, on the western bank of the Nile, near the tomb of the pharaoh in the Valley of the Kings.

Today we know it as Ramesseum, since Jean-François Champollion baptized it that way when he identified a cartouche with the king’s name.

In the time of Ramesses, however, it was known as “House of millions of years of User-maat-ra-setepenra that unites with Thebes-the-city in the domain of Amun”. User-Maat-Ra Setepenre was the name that Ramesses took when he ascended to the throne.

The works of the Ramesseum lasted almost twenty years, from the beginning of the reign of Ramses until its conclusion in the year 21.

The best specialists in the country participated in the construction, under the command of the master builders Penra and Amoneminet, two trusted ministers of the pharaoh.

They both designed it to be one of the largest temples in western Thebes. Its almost six hectares of surface include the main temple, a temple dedicated to his wife Nefertari and his mother Tuya, a palace and the annexes dedicated to the administration of the sanctuary.

It is known that some blocks of temples from the 18th dynasty were reused for the construction. This building, created with the best materials, built in stone and destined to remain standing forever, was badly damaged by an earthquake.

Protector of his people

Ramesses’s constructive fever might seem like a form of megalomania or self-centeredness; but in reality it responded to deeper motivations.

On the one hand, the king wanted his subjects to know that he was the strong and dominating arm, the one that could not be defeated.

This is reflected in the decoration engraved on the Ramesseum, both on the exterior and interior walls: scenes of battles abound, with the king leading his army victoriously and defeating the forces of evil, personified by his enemies.

As in other temples, Ramesses had episodes of the Battle of Kadesh and other confrontations against foreign peoples recorded in the Ramesseum. Likewise, he reproduced the parade of some of his many sons and daughters.

Some scenes from the Ramesseum show the pharaoh together with various gods of the Egyptian pantheon, and even himself is represented as a god.

Indeed, the royal buildings of the New Kingdom not only showed the military or political power of the pharaohs, but also their divine status, something that is evident in the Ramesseum.

Like other temples spread across western Thebes, the Ramesseum was a place of worship for both the god Amun and the deified king.. Through various rituals, festivals and ceremonies the constant regeneration of the pharaoh was symbolized.

These ceremonies were necessary for him to rejuvenate and revitalize both while he was alive and after his death. The Ramesseum was thus united in a symbolic way with the tomb of the pharaoh in the royal Theban necropolis; Shrine and sepulcher, despite being physically separated, formed a unit destined to keep the deceased in immortality.

Ramesses, equal to the gods

The identification of Ramesses with Amun was reflected in the sculptures. In the innermost area of the temple the sacred statue of Amun was housed with the features of the sovereign.

Another important local festival was the Beautiful Valley Festival, in which the statue of Amun departed from his residence in Karnak to visit the “Millions of Years temples” of the pharaohs and revitalize the dead buried on the western bank.

The image was moved by boat, along the river and the canals, to the docks located in front of the Millions of Years temples. Then it was placed in a transportable ship that was carried on the shoulders of the priests to the interior of the Ramesseum,where the most secret ceremonies were held.

Although it is true that the Egyptian temples were not designed to welcome parishioners, the people could access the first courtyards.

In these places great colossi of the pharaoh rose to which the people made offerings and raised their supplications in the course of some festivals.

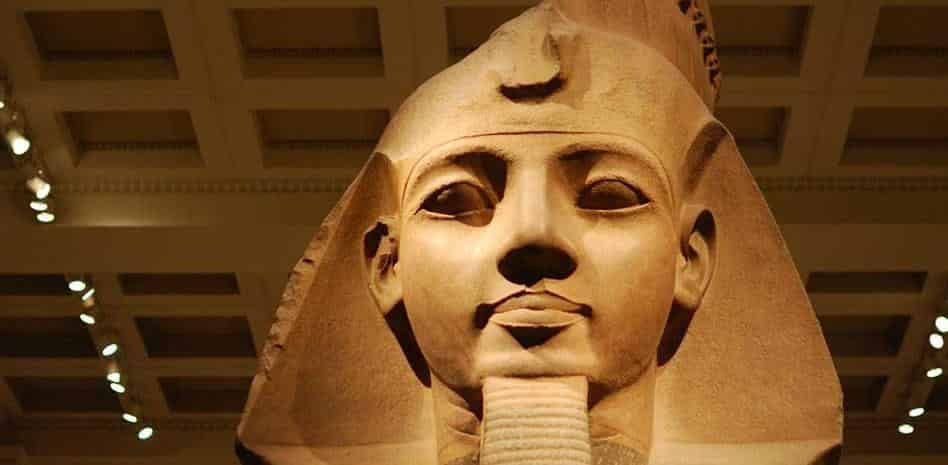

In the Ramesseum this function was fulfilled by a colossus of extraordinary dimensions, 18 meters high without counting the base, placed in the first courtyard, just in front of the pylon that gives access to the second courtyard of the temple.

It received the name of “Ramses Sun of the Sovereigns”. An ambitious project is currently underway to rebuild the fallen colossus from the more than five hundred fragments that have been located from the statue.

Source:

National Geographic.

Memoirs of Ramses the Great. C. Lalouette. Criticism, Barcelona, 2006.