Three millennia ago, Egypt was at the height of its empire. After the war campaigns of Senusret III and a period of splendor and Egyptian pax during the government of Amenhotep III, and having saved a phase of weakness and decline led by pharaohs such as Akhenaten and Tutankhamun, the good times returned hand in hand with a new dynasty.

Ramses II was a warrior pharaoh who devoted himself to war campaigns in order to maintain the empire’s domain and stop the increasingly daring Hittite penetrations.

The Battle of Kadesh between both armies should have been the turning point, but it ended practically in a draw.

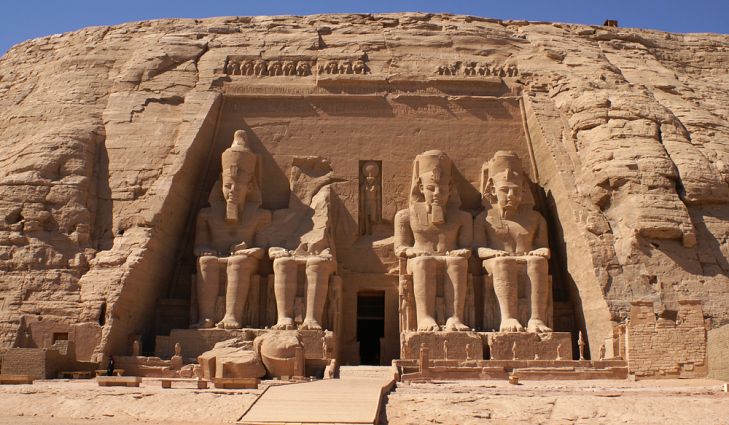

However, Ramses’ capacity for self-aggrandizement was proverbial, and he not only claimed a landslide victory but also planted the country with commemorative monuments of the deed. The Abu Simbel temple is perhaps the most spectacular.

It is a hemisphere, excavated in the rock (in fact, the name Abu Simbel means pure mountain), which was endowed with an imposing façade thirty-four meters high and thirty-eight meters wide with four giant statues of the pharaoh himself, each measuring twenty-two meters.

It took twenty years to build (1284-1264 BC) on the Nubia border.

Another temple was built next to it (dedicated to the goddess Hathor and Ramses’ favorite wife Nefertari); also grandiose, although somewhat smaller.

Abu Simbel, which remained forgotten for centuries buried by tons of desert sand, was rediscovered in 1813. But it entered the History of Art with a capital letter in the twentieth century when the Aswan Dam construction project threatened to leave it submerged under the waters of Lake Nasser, along with many other monuments.

UNESCO launched an initiative to save it in 1959, and it was dismantled stone by stone to rebuild it two hundred and ten meters further at an altitude of sixty-five, safe from any flood.

One of the peculiarities of Abu Simbel is that twice a year, the sun’s rays penetrate from the entrance to the Sancta-Sanctorum, passing through the pronaos and the colossi and hypostyle rooms to illuminate the statues of the gods Amun, Ra-Heractates, and the deified pharaoh himself for twenty minutes, leaving Ptah in the dark to represent darkness.

It is believed that the dates the sun illuminates his face commemorate his birth and the day of the coronation of his long reign that would last sixty-six years.

Traditionally it occurred sixty-one days before and after the winter solstice, on October 21st and February 21st, anniversaries of the pharaoh’s coronation and birth, respectively. But since the move, and due to the displacement of the Tropic of Cancer during the last three-thousand-two-hundred and eighty years, the calendar was left with a slight lag, moving to October 22nd and February 20th.

Those days are when the so-called perpendicular takes place, celebrated by modern Egyptians with festivals and various shows. If you have the chance to be there, don’t miss it!