These massive reptiles, which posed a threat to those living along the banks of the Nile, were both objects of fear and devotion among the ancient Egyptians.

Within the diverse fauna of the Nile, crocodiles have always been one of the most distinctive and unsettling inhabitants. Measuring up to twenty feet in length, with their powerful jaws and scaled shields, they presented a constant and harrowing menace to the ancient Egyptians, who were accustomed to navigating and fishing in delicate papyrus boats.

It is not surprising, therefore, that this formidable creature held a significant place in Pharaonic culture.

For the ancient Egyptians, crocodiles symbolized danger. Some hieroglyphic symbols depict these saurians with one or more knives embedded in their bodies.

Furthermore, certain terms were inscribed using a crocodile-shaped symbol to convey concepts related to “aggressiveness” and “greed.”

These stealthy reptiles posed a threat to anyone venturing near the Nile’s shores, including other animals. Thus, a papyrus from the New Kingdom records spells needed to protect the horses crossing the river.

As for humans, the danger of crocodiles became a recurring theme in literature. In the “Satire of the Trades,” for instance, the risks faced by a washerman working along the Nile’s banks, surrounded by crocodiles, or a fisherman sharing the river with these creatures, are highlighted.

In “Dialogue of the Desperate Man with his Ba,” the protagonist exclaims, “Look, my name is more reviled than the stench of crocodiles, more than sitting on a sandbar teeming with crocodiles.”

In the “Westcar Papyrus,” a fantastical crocodile plays a role in a tale of jealousy and revenge.

In this story, the priest Ubaoner discovers his wife’s infidelity and, upon learning of a rendezvous planned by the lovers, he creates a wax crocodile that, through magic, comes to life and captures his wife’s paramour, dragging him to the river’s depths. Following several incidents, the creature devours the unfortunate man, while the wife meets a fiery demise.

Divine Metamorphoses

However, the crocodile wasn’t merely a terrifying creature. It also inspired profound reverence, leading various deities to assume its form.

For instance, the falcon god Horus transformed into a crocodile to retrieve his father Osiris from the depths of the river, where he had been slain by his malevolent brother Set.

The crocodile was also associated with the solar god Ra during his resurrection as he emerged from the Nun, the primordial waters.

The quintessential crocodile deity was Sobek, whose name quite literally translates to “the crocodile.” Initially depicted in the form of this creature, Sobek eventually came to be represented with a human body and a crocodile head.

During the Middle Kingdom, Sobek became intertwined with solar symbolism, and by the 13th dynasty, he was embraced as the patron deity of royalty.

Sobek was a god of fertility, vegetation, and creative power. He presided over the waters and wetlands while also serving as a protective deity, as the Egyptians observed his fierce defense of his eggs.

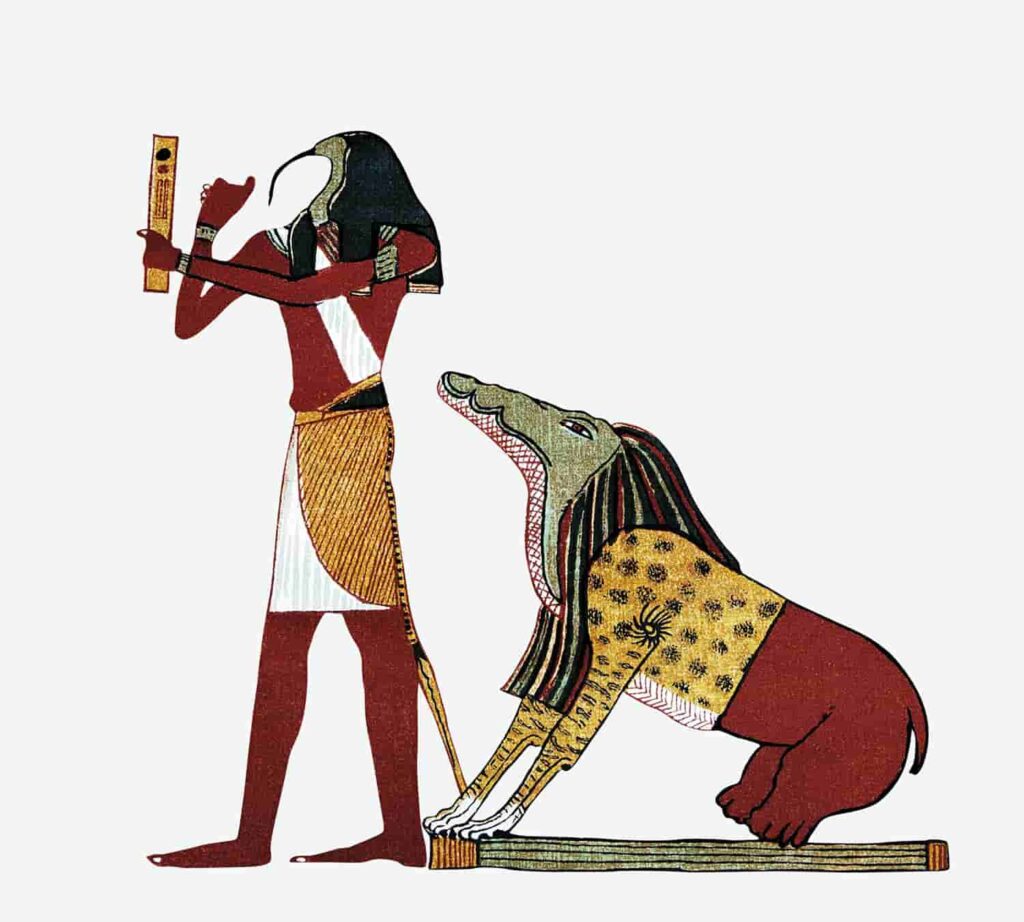

Ancient Egyptian iconography featured numerous hybrids of crocodiles and other animals. An aquatic manifestation of Horus possessed a crocodile’s body and a hawk’s head.

The benevolent goddess Taweret, a deity of the home and a protector of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and birth, had the head of a hippopotamus, lion’s legs, human breasts, and a crocodile’s tail. On the other hand, Ammit, a monstrous entity tasked with devouring the souls of the deceased who failed Osiris’ judgment, sported the head of a crocodile, a lion’s body, and a hippopotamus’s hindquarters.

Source: Elisa Castel, National Geographic